It was the summer of 1985. Jill and I were taking the first steps into our thirties, and while our goals were still ambitious, they were no longer earthshaking. The dream of changing the world had begun to fade, and we had started to focus on the smaller world right around us. We wanted what everyone wanted: a safe home, a healthy family, a few good friends, enough money to pay the bills, and some time to enjoy it all. Measured against those criteria, we were doing well. We’d been married for almost four years, had bought a house in Connecticut, and were soon going to have a baby.

It was the summer of 1985. Jill and I were taking the first steps into our thirties, and while our goals were still ambitious, they were no longer earthshaking. The dream of changing the world had begun to fade, and we had started to focus on the smaller world right around us. We wanted what everyone wanted: a safe home, a healthy family, a few good friends, enough money to pay the bills, and some time to enjoy it all. Measured against those criteria, we were doing well. We’d been married for almost four years, had bought a house in Connecticut, and were soon going to have a baby.

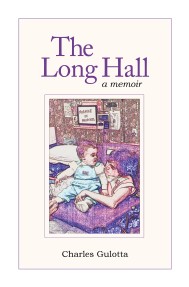

The circumstances leading up to those events, and the ordeal that followed, are the subject of a memoir I’ve recently finished. It took me nearly three decades to write The Long Hall. Not that I was working on it with anything that could be described as diligence. Mostly, I was avoiding the whole project, because it seemed like an insurmountable task to pin down the details and capture the thoughts and emotions. The truth is, I doubted that I could do it justice. The more time that slipped by, the less I wanted to go back and re-open the wounds. But it’s a story that deserves to be told, especially now that my daughter Allison is about to have a baby of her own.

The Long Hall recounts, in a series of eighty-five connected scenes, our adventures into both the mundane and the unimaginable. It’s filled with humor and heartbreak, a lot of good memories and a lot of unbearable ones, too. This excerpt is one of those scenes.

Braxton Hicks

Very close to the end of the pregnancy, we were out walking near our home. Jill had been having contractions, on and off, for days, and she thought activity would hasten things along. We went to the end of our short street, then followed a path that led to the public library. We spent about an hour looking through books and magazines, until Jill got restless and wanted to go home.

Outside, the sky had darkened and about a minute from the library, it began to rain hard. It was July, so the maple trees were thick with foliage. We noticed the ground was dry under each one, and we sprinted from tree to tree. But the rain turned into a downpour. The trees soon lost their battle with the torrent, the dry ground vanished, and we were getting drenched. About halfway home we realized there was no shelter and just ran the rest of the way, screaming and laughing — pretty much the same as we had months earlier, when we first spotted the doughnut in the plastic tube. We were soaked. We undressed just inside the front door and took a shower together. Our skin was cold from the rain, and the warm water mingled with the laughter, and with the unspoken sense that we were racing toward something that was racing toward us.

A few days later we watched the movie, The Competition, on television, then left for the hospital at eleven-fifteen. Jill’s bag was already packed because we’d been through this routine at least twice, thinking she was ready to deliver, only to find out it was false labor. When a baby is ready to arrive, the mother’s body begins a series of contractions in order to push the infant out. But prior to this process there is often a practice period, a dress rehearsal of sorts. It isn’t time to deliver, but it feels like the real thing. Women refer to these early contractions as Braxton Hicks.

“She wasn’t ready to go. She was having Braxton Hicks.”

Women are born knowing about these things. Men have to listen and learn through experience, passing through several stages of decreasing ignorance before they can comprehend what’s going on. The first time I heard of Braxton Hicks, I assumed it was the name of a medical office. Then I thought it might be some kind of rash. I rarely understand anything the first time around, but I eventually made the connection with false labor.

The key point, I guess, is that you don’t know it’s Braxton Hicks at the time. You only find out when you come home without a baby. With each false alarm, it seems more and more as though the real thing will never happen, even though some part of your mind knows it must. In a strange way, it was similar to watching someone endure a long terminal illness, the way I watched my father inch slowly downhill. You may think they’re about to die, then they pull back, and for a little while seem to be heading toward recovery. Each time, there is that sense of relief, because you’re never really ready. But now the contractions were closer together and felt different. I reminded Jill that she had said that before.

“It feels different,” she said.

“That’s what you said the last time.”

“But those weren’t real. This is real.”

“How do you know?”

“Because it feels different this time.”

We called the doctors’ office and the nurse told us to get to the hospital. So this was it. Here was that car ride I’d thought so much about, the one you see on television and you think, please don’t let it happen like that. I’d practiced it over and over in my mind. We’d done a trial run the week before. We’d been to the hospital for the new parents’ tour. We should’ve been ready, and we were. Everything was under control. My driving was smooth and effortless. We could have been going to the supermarket for a loaf of bread, except it was almost midnight, and you leave your house at that hour only for life-altering events.

After parking the car, I felt bothered for just a moment by the bright yellow EMERGENCY sign. I opened Jill’s door and she climbed out. Then we walked slowly through the doors of Bridgeport Hospital.

It was 11:40. The day we would have our first baby — July 12, 1985 — was itself about to be born. We were in that moment when everything changes. The bridge from here to there was twenty feet of linoleum. We stopped at the desk and answered questions. Name, address, insurance. A thin man in pale green scrubs appeared out of nowhere, steered a wheelchair up behind Jill, snapped the footrests into position, and pushed her toward the elevator. We had no way of knowing, but Jill had just walked the last twenty feet she would ever walk. Right there. That faded, scuffed stretch of hallway. She was thirty years old. I was twenty-nine. We had been on top of the world for the past four years. But the world rolls. Sometimes you roll with it, and sometimes it rolls on top of you.

I was surprised to notice that my hands were shaking. I was having one of those conversations in my head, like the one I have when I’m on an airplane that’s about to take off.

“There are thousands of flights just like this every day.”

“I know that.” (This is me talking to myself.)

“Every day of the year.”

“Yes.”

“Almost without incident.”

“True.”

“So what are you nervous about?”

“I didn’t think about those other planes. I wasn’t on them.”

“This plane will have a problem because you’re on it?”

“I should get off now and save these other passengers.”

It was the same conversation I’d had so many times while driving across bridges. Worrying that the bridge would fall actually prevented it from happening, because the coincidence of this massive structure giving way at the very moment I was thinking about it was too unlikely. Sure enough, I’d always made it safely across, along with hundreds of other drivers, all seemingly unaware that I’d just prolonged their lives.

Logic, of course, is on the side of the optimists. More than a hundred million babies are born each year. How often does something go wrong? Statistically, almost never. In only about three percent of all births, there’s a serious problem with either the mother or the baby. However, that still works out to thousands a day. We don’t hear about those incidents because they’re small and private. There’s no debris field or black box, no eighteen-wheelers doing headstands after a vertical drop. Just long hospital stays, years of struggling, quiet funerals. Newspaper headlines are reserved for airplanes slamming into mountains and bridges falling into rivers.

I followed as the attendant backed Jill into the elevator. There was something comforting about the way he shuffled his feet, and how he pushed the buttons without looking. Another night, another baby. Still, it felt like a dream, and not an entirely pleasant dream. For one thing, I was sure I’d never get used to seeing Jill in a wheelchair. For another, I hadn’t completely shaken that vision I’d been having, the one where I was in the grocery store with a newborn baby, and Jill wasn’t there. I was looking out the airplane window and could see the ground rushing up. I could feel the roadway sinking away as the bridge began to collapse. But I wasn’t sure if it was really happening, or if it was all in my head. I shuffled along with the attendant as he pushed Jill out of the elevator and into the future. I looked ahead, down the long hall, and tried to see where we were going. My heart was full, and racing. My movements, I knew, were calm and smooth, just as my driving had been between our home and the hospital. I was all right, and yet I was not all right. There was a wheel rotating inside my chest, turning to fear, then joy, then a hazy uncertainty, and back to fear. Not a panic attack, exactly, but something like it. A false panic attack. An emotional Braxton Hicks.

The Long Hall is 320 pages, and can be purchased for $12.95 from Amazon.com. The e-book edition is also available, for about $3.99 US, in any country where Amazon has a Kindle store.

If you have found any enjoyment and derived any value from this blog, I think you will like the memoir just as much. I hope so. Thank you for reading, and for helping me get the word out about this book.

ranu802

August 24, 2014

It is 8:36 a.m. I was reading your memoir and wondering at the same time, how it would end, unfortunately I’d have to wait.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 25, 2014

The scene described in the post isn’t even close to the end, Ranu.

LikeLike

Noreen

August 24, 2014

It was hard for me to read it, reliving with you, but I can’t wait to finish.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 25, 2014

Thank you, Noreen. I look forward to your reaction.

LikeLike

Personal Concerns

August 24, 2014

this is an absolutely wonderful account. don’t know why but it did leave me moist eyed! i so want to read everything now!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 25, 2014

I appreciate your interest, PC, and your willingness to become emotionally involved.

LikeLiked by 1 person

claywatkins

August 24, 2014

I wanted more – it’s well written. I wanted to know more of your story – it must have been very difficult to write – to get the details in the right order and to process your feelings and all. Nice work.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 25, 2014

Thanks, Clay. One of the challenges was having to deal with the way our minds distort memories, especially after so much time has passed.

LikeLike

randee

August 24, 2014

I was reading this as I walked around my house, going about my morning business. At one point, I stood still, couldn’t move, had to focus, read faster, see what happens. You know the point. Excellent writing!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 25, 2014

Thank you, randee. I’m glad to know that I succeeded — at least to some degree — in conveying the complex emotions of that day.

LikeLike

She's a Maineiac

August 24, 2014

This is a huge accomplishment, congrats on your book. You are brave to write about these moments. I can’t imagine how painful reliving them must have been for you. Thank you for sharing part of your life with us, I look forward to reading more.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 25, 2014

Darla, you know as well as anyone how daunting it is to write about these major life moments. But something compels us to do it, and after we’re done, we feel as though we’ve moved, again, to a new place.

LikeLike

She's a Maineiac

September 12, 2014

I finished reading your book (I read it in two days, couldn’t put it down). I want to thank you for sharing this part of your life with us. Your writing is incredible. I really don’t have adequate words to convey how much Jill’s story touched me. I went through so many emotions reading about your life together and I will never forget it. As a matter of fact, I think of her and you often. I’m viewing life and love and death in a new way. Thank you.

I sincerely hope that writing about it has brought some peace to your mind. And congratulations on the impending grandbaby. Enjoy every minute!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 13, 2014

Thank you, Darla. I know you can relate to how difficult it is to re-live certain events, and put them into words that make any sense. Thank you for your ongoing encouragement. It’s meant a lot to me.

LikeLike

Angelo DeCesare

August 24, 2014

Charlie, congrats to Allison on her impending motherhood and to you on your impending grandfatherhood! I just purchased your book on Amazon. I wish you great success with it!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 25, 2014

Thank you, Ang, for your encouragement and support. You’ll always be my oldest friend, and I treasure that fact.

LikeLike

Margo Karolyi

August 24, 2014

A book I shall definitely buy and certainly must read. The excerpt was wonderfully written, moving, and heartfelt. I look forward to reading the rest of your memoir.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 25, 2014

I appreciate your feedback, Margo. I’d love to hear what you think about the entire book.

LikeLike

Jac

August 24, 2014

This will be hard to read, but I know not nearly as hard as it was to write. I am so grateful that you were able to do it, though, as it all still feels like a bad dream. Jill was such an amazing woman and an energizing force in our family, and she truly was my best friend. I know this book will do justice to who she was and what you two had together. I hope that Allison gets even more of a sense of what a great mother she has, and I know she will be just as great.

❤ Where there's a Jill, there's a way ❤

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 25, 2014

I doubt that I did the story justice, but I tried my best. I hope you like it.

LikeLike

Jac

August 25, 2014

Your best always comes from love, so I know I will love and treasure it.

LikeLike

Anonymous

August 24, 2014

I have been following your blog for years, and have always enjoyed your writing because it is honest and heartfelt. I just purchased “The Long Hall” on Amazon and can’t wait to start reading it. Thank you for letting your readers into such a personal aspect of your life. I can’t imagine it was easy, but I am sure it will be worth it.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 25, 2014

Thank you. I appreciate all feedback — even the anonymous kind.

LikeLike

vgfoster

August 24, 2014

I just downloaded your memoir and cannot wait to devour it cover-to-cover! Based on the excerpt, and on the quality of your regular posts, I know it will be well-written and full of truth and love. But I also know it will break my heart. Life often does. Our memoirs both begin in the summer of 1985 and took decades to write! Yours will, no doubt, leave me breathless.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 26, 2014

Thank you, Vanessa. And now that I’ve finally finished this book, I have time to get back to reading yours.

http://about.me/vgfoster

LikeLiked by 1 person

icedteawithlemon

August 24, 2014

I have tears already. I will be purchasing your book today, and perhaps in a few weeks you will do me the honor of signing it. I’m sure it took tremendous courage to share your story and to “re-open the wounds,” but I am equally sure that you did so with the beauty and eloquence, humor and insight that I have come to expect and admire in your writings.

From one of my favorite poems, “On Joy and Sorrow” by Kahlil Gibran:

“Your joy is your sorrow unmasked.

And the selfsame well from which your laughter rises was oftentimes filled with your tears.

And how else can it be?

The deeper that sorrow carves into your being, the more joy you can contain.”

Peace be with you, my friend, and congratulations on publishing yet another book, and congratulations, too, on the upcoming birth of your grandchild!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 26, 2014

Thank you, Karen. Your feedback is always encouraging, and I appreciate it. About our respective books: I’ll sign mine if you’ll sign yours. We can’t wait to see you.

LikeLike

jeanjames

August 24, 2014

I had such a knot in my stomach reading this excerpt from your book. I look forward to reading more. Congratulations on becoming a grandfather!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 26, 2014

Sorry about the knot, Jean. This story gave me a lifelong respect for what you and others in the nursing field do every day, almost always unnoticed and unappreciated.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Marie

August 24, 2014

I fear any comment will feel trite given the raw tenderness of such an intimate sharing. Thank you for trusting us with the most sacred pieces of your story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

bronxboy55

August 26, 2014

Marie, you couldn’t be trite even if you wanted to.

LikeLike

Marie

August 26, 2014

Charles, I read your memoir on Sunday. It is a testament to your immeasurable heart that you could create something so beautiful from the darkest corners of an impossible experience. Your humor and wit are as ever-present as your compassion and integrity. My life is richer for sharing this chapter of yours.

LikeLike

dearrosie

August 24, 2014

Congratulations on the publication Charles. I can tell from your excerpt (which left me with a lump in my throat) that the book is a well-written honest memoir. I can’t wait to read it. I’ve already downloaded it.

much love

rosie

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 26, 2014

Thank you, Rosie. I hope you’re working on yours, too. Let me know if you need to be nagged.

LikeLike

susielindau

August 24, 2014

Wow. It sounds so ominous. She never walked again? How horrible. You’ve got me on the edge of my chair.

Congrats on completing your memoir! It sounds like an excellent read!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 26, 2014

Thanks, Susie. I hope it’s at least nearly as good as it should have been.

LikeLike

subodai213

August 24, 2014

Charles..be careful. You may just get Freshly Pressed for a third time. What a writer you are. Oh my gosh.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 26, 2014

I don’t think they would Freshly Press a post like this, especially because there’s a book for sale attached to it. But thank you.

LikeLike

Ruth Rainwater

August 24, 2014

Oh, you hooked me and reeled me in. Now I’m going to have to buy your book. 😀

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 26, 2014

I’m happy you liked it that much, Ruth. I hope you’re well.

LikeLike

Ruth Rainwater

August 26, 2014

I am doing okay – stable at the moment. And that’s a good thing. 😀

LikeLike

thecontentedcrafter

August 24, 2014

This is a book I want to physically hold. I shall endeavour to get a copy sent here. Your writing holds an immediacy and an openness and honesty not often found. Charles, you move me. Your blog posts so often bring smiles and laughs to accompany the factual, pragmatic truths of life and now this small excerpt from your memoir, without warning, hurls me into an emotional, breath-holding journey. You are a master! Thank you for introducing me to this next level in you. .

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 26, 2014

Pauline, you always say things that take me completely by surprise. You’re just too kind.

LikeLike

thecontentedcrafter

August 26, 2014

I’m not being at all ‘kind’. I just try to put into words what I’m feeling 🙂

LikeLike

Val Boyko

August 24, 2014

This touches me deeply … And yes, like so many others who are captivated, I can’t wait. Thank goodness for kindle.

Your writing is very special Charlie. I’m so glad to have found you.

Val x

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 27, 2014

Thank you, Val. And, yes, those e-readers are amazing. I think print books and ebooks are both here to stay.

LikeLiked by 1 person

wheremyfeetare

August 25, 2014

I just purchased your memoir on my kindle. What I read here was very moving, can’t wait to read the rest. As others have already commented, thank you for sharing such a personal event.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 27, 2014

I appreciate your support, Geralyn. I hope you like the rest of the book.

Have a great run on Labor Day.

LikeLike

wheremyfeetare

August 27, 2014

I’ll be starting your book today. I really like your writing style on your blog and look forward to reading more in your book. Best of luck!

LikeLike

rangewriter

August 25, 2014

Yeah! I knew you were up to something! I’m so excited. Can’t wait to set aside some time to read The Long Hall!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 27, 2014

How did you know?

LikeLike

rangewriter

August 27, 2014

Well, probably you told us on your blog at some point, but that’s not exactly how I knew because I never remember anything for that long. But it was a feeling I had, perhaps the length of time that would pass between posts? It’s that intuitive thing, I guess.

LikeLike

rangewriter

August 27, 2014

BTW, I’m reading it right now! Loving every delicious word.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 28, 2014

Coming from you, that means a lot.

LikeLike

Betsy Erker (Coniglio)

August 25, 2014

Hello there. Allison and I were good friends growing up in Danbury and as a kid I felt so sad that Allison’s mother wasn’t around and that she was sick. I never knew the whole story, and never wanted to ask. You raised a very strong and kind daughter and thank you for all that you did for me as a kid. Your excerpt stirred a very intense emotion in me and I’d like to read the rest. Take care!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 27, 2014

I remember you, Betsy, but didn’t know you and Allison were still in touch. She had a few wonderful friends in Danbury, and you were certainly one of them. I hope you’re doing well. Thank you for the thoughtful comment.

LikeLike

Andrew

August 25, 2014

Got my copy.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 27, 2014

Thanks, Andrew. Please let me know what you think.

LikeLike

Andrew

September 4, 2014

I am just about half way through – excellent writing on a very difficult subject. It’s hard to imagine going through that and I commend your ability to be able to share that story. Not sure I could approach a subject like that with skill and grace you have.

However, I am going to finish reading the book before I give it 5 stars on goodreads and amazon. 😉

LikeLike

Chichina

August 25, 2014

Thank you for sharing such a private and tragic piece of your life, Charles. I just ordered your book, and would be happy to provide a review after reading it. Best of luck to a fellow author!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 27, 2014

Best of luck to you, too, Sonia. I feel as though I abandoned you with your most recent book, but I’m glad you went ahead and published it, anyway. I just bought the Kindle version, and promise to finish reading it this time.

http://risingsun1blog.wordpress.com/

LikeLike

Chichina

August 27, 2014

No problem….. It had to go through a million edits after I gave you the manuscript, so it is just as well… I look forward to reading your story….. and are you….. ahem…. going to put a piece in the local paper and do an author signing at the bookstore? I’m re-editing my other book now, and once its available again, I’ll try to do some promotion….. Good luck!!!! P.S. I’ll come to your book signing in the interest of solidarity.

LikeLike

Sarah

August 25, 2014

I’m so proud of you for finishing this, Charles. You know how eager I am to read it. I know, however, that it will be difficult for me because, even knowing what I know, I read the excerpt with dread. For a brief period of time, I watched you doing a wonderful job raising a wonderful Allison. I know her parenting will honor both you and Jill. I’m off to Amazon now to order my copy and I look forward to the day you can sign it for me in person.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 27, 2014

Thank you, Sarah. You are a wonderful writer and teacher, so your positive feedback always means a lot to me. Your friendship means even more.

LikeLike

Allison

August 25, 2014

I don’t think I will ever be able to clearly express what a gift this book has been for me. You have given me a chance to get to know my mom, and you, in a way that was never really possible. Not only that, but you have allowed me to feel her presence at a time when every woman wants her mother – just when she is about to become a mother. Now I am able to imagine what she might say or do, and it’s because of your strength and courage to write this story, and the clarity in which you have done so, that I can do that. I am so proud of you, and I am so proud to call you my father.

LikeLiked by 4 people

bronxboy55

August 27, 2014

If what you say is true, then I’ve accomplished what I set out to do. Your Mom would have been immensely proud, as I am, of the person you are. And I know you will be exactly the kind of mother she wanted so much to be.

LikeLike

Chelsey Rogerson

August 25, 2014

Absolutely brilliant excerpt!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 27, 2014

Thank you for that, Chelsey, and for being the great friend that you are to Allison. I hope we can continue to exchange ideas.

LikeLike

Betty Londergan

August 25, 2014

Wow!! I seriously can’t wait to read more—l’ll buy it as soon as I get home! Congratulations, Charles!! What a big moment for you, and huge congrats on being an impending granddad!! I’ll be a step-granny in end of March and cannot wait!

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 27, 2014

Congratulations to you too, Betty. If you like the book half as much as I liked The Agony and the Agony, I’ll be happy.

(As soon as you get home? You go home?)

LikeLike

foxress

August 25, 2014

I really love your writing. I’m very sorry for the heartbreak I know is coming in the story. But I thank you sincerely for sharing your tremendous talent.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 27, 2014

Thank you for the kind words, Linda. I appreciate your support.

LikeLike

earthriderjudyberman

August 25, 2014

You told me once that you didn’t think ‘riveting’ described your writing (I think that was the word). Well, it is. Your excerpt above is excellent, compelling. I was left wanting to read more. Now I’ll just have to wait for it in the mail. I just ordered it.

LikeLike

earthriderjudyberman

August 26, 2014

I posted this story on my Facebook page.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 27, 2014

Judy, thank you as always for your encouragement. And speaking of Facebook, I just sent you a friend request. For some reason, I thought we’d already done that.

LikeLike

earthriderjudyberman

August 27, 2014

Now, we’re connected. Thank you, Charles. Great “seeing” you on Facebook. 😉

LikeLike

Ann Koplow

August 26, 2014

You are an amazing writer, Charles. I will read your book with gratitude and growth, I know.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 28, 2014

That’s a wonderful thing to say, Ann. Thank you.

LikeLike

Diane Henders

August 26, 2014

Congratulations on your book, Charles! I’m off to Amazon now to buy it.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 28, 2014

Thanks, Diane. I’m just trying to catch up to you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Diane Henders

August 28, 2014

I finished it in one ravenous gulp last night – magnificent! It was heart-breaking, gut-wrenching, and beautiful. Well done, Charles! I’ll post a 5-star review on Amazon for you.

I’m only sorry that such wonderful writing had to come at such a terrible personal cost.

LikeLike

Philster999

August 26, 2014

Congrats Charles! Well done! I too am about to head over to Amazon to order my copy.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 28, 2014

I just sent my submission to the contest you told me about. Thank you again for that. See you in a few weeks, I hope.

LikeLike

Elyse

August 26, 2014

No matter what the story is, Charles, you always tell it with heart, love and humor. I will be buying your book. I hope that telling the story helped bring back more joy than pain.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 29, 2014

I imagine most memoirs are difficult to write, and there’s a tendency to avoid doing it for as long as possible. But some things just have to be written, and in the end, it’s a constructive and rewarding process.

Thank you for always being here, Elyse.

LikeLike

Elyse

August 29, 2014

I am reading it now. It is breaking my heart.

And the setting is very familiar — I grew up in Westport (Greens Farms, right by Southport beach) and I was born in Bridgeport Hospital.

I won’t say any more until I’m finished reading.

LikeLike

Terri S. Vanech

August 27, 2014

Just bought the book and will now sit by the mailbox waiting for it! 🙂 Congratulations on its publication. Thank you for sharing your story with us all.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 29, 2014

Thanks, Terri. And I have to ask: Do you have a memoir in the works? I’m sure a lot of people would love to read your story.

LikeLike

Terri S. Vanech

August 29, 2014

You are very sweet. I toy with writing a memoir quite a bit. From the time I was lost in books as a child I’ve wanted to write one of my own. Maybe yours will inspire me to finally do it!

LikeLike

Nick

August 28, 2014

I just finished the book and cried uncontrollably. To know her was to love her. Your book is filled with every human emotion. I know you didn’t write it for any self recognition or self gratification. But words like bravery, honor, loyalty and love only scratch the surface of this story. She is my saint and you are my hero.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 29, 2014

I’m glad we got to spend some time together back then, Nick. Happy memories of the past can cause a hollow feeling in the present, but it’s still better to have those memories. In the end, that’s all we have. Thank you for the beautiful comment, and for the time we had with our families this summer. I hope we can maintain that level of contact from now on.

LikeLike

melissa

September 2, 2014

Charles, I am so happy to see this account of your life now has a home in a published book. I cannot wait to read it. I checked out your listing on Amazon, and noted the beautiful review left for you from your daughter. My children are still young enough that I remember their births with vivid detail (though perhaps I always will), and I hope you know what a treasure, what a gift this book is for your daughter, in connecting her as she said with her mother. You are brave to have conquered the writing of such a story, and I thank you for sharing it with us.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 2, 2014

Thank you, Melissa, not only for this most recent comment, but for all of your many words of encouragement and advice. On both professional and personal levels, you are a valued friend.

LikeLike

a-listerrogue

September 2, 2014

Reblogged this on A Fine Mess.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 2, 2014

Thank you for the re-blog. I appreciate it very much.

LikeLike

Ruth Rainwater

September 2, 2014

I finished the book today during chemo. And wow! I have been riveted and couldn’t put this book down since I started reading it a couple of days ago. I admire your courage and dedication in getting the words on the page (and e-reader). I left reviews on Goodreads (as myself) and on Amazon.com (I’m Grandma Zona – long story!) I am just blown away still. I can’t even start on another book until the emotions and tears settle down.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 3, 2014

Thank you, Ruth, for the direct feedback here and the online reviews. I hope the chemo goes well, and that you’re feeling better very soon.

LikeLike

lostnchina

September 3, 2014

Charles, where do you find the time to write a post every week then go on to write a 320-page memoir?! And knowing you, I’m positive that the first 120 pages aren’t blank. filled with grocery lists from 1971, nor recipes for gingerbread men made with gingko biloba. I’m going to get my copy now and look forward to reading it. Congratulations!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 3, 2014

I take the time I should devote to updating my resume and filling out job applications, and I write, instead.

Thanks, Susan. I hope you like the book.

LikeLike

Noreen

September 3, 2014

I finished the book a couple of days ago, but couldn’t find the words to express how I feel. I still can’t. But thank you for writing the story and for sharing it again with all of us. Your descriptions of Jill before and after the stroke bring her to life again. I laughed and cried and was emotionally drained, but also renewed. I have always admired you for how you were always there for Jill and how you raised a baby by yourself. Allison is a wonderful woman and I know how proud of her you are. And she is also proud of you, as I am. I also want to compliment you on your writing. It wasn’t just the story, but how you put it together that held my eyes to the page. It was a good book. ❤

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 3, 2014

Thank you, Noreen. It’s hard to believe that twenty years have passed since she died. The nine years of her illness seemed much longer. I’m sure you know what I mean.

LikeLike

Arindam

September 5, 2014

Sir Charles, thanks for making this book available via Kindle. Now I am looking forward to read it soon.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 6, 2014

Thank you, Arindam. I’m sorry we’ve been out of touch (my fault).

LikeLike

wheremyfeetare

September 6, 2014

Charles, I just finished your book.I found myself hiding my kindle under my desk at work yesterday so I could keep reading. It’s hard to write something here without sounding trite; I can only imagine how difficult it must have been to write this book. But, I thank you for sharing it with the world and giving us a glimpse of who you and Jill were. After reading the last page I felt sadness as well as happiness for what you, Jill and Allison accomplished through love and determination. And congratulations to Allison!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 8, 2014

Thank you, Geralyn, for all your kind words. They mean a lot.

LikeLike

Marie M

September 6, 2014

Masterful, poignant, real. Completely understandable that it would take decades to make into a coherent story. Thank you for sharing your heart and soul.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 8, 2014

And thank you, Marie, for helping me find my way through the tangle of memories and emotions.

LikeLike

Patti Kuche

September 8, 2014

Charles, I don’t know what to say in the light of such powerful emotion, depth and strength with which you have brought Allison to this point where she is about to become a mother herself. My best wishes to you all and I salute your fine work indeed. Off to shop at Amazon now!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 9, 2014

Patti, your ability to tell stories through photographs is one I respect and admire, and so I take great satisfaction in your feedback. Thank you.

LikeLike

accidentallyreflective

September 10, 2014

How I missed this post I do not know… I can again relate to what you say… I could NEVER however, relay it the way you do. Amazing.

I am buying your book. Enough said. 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 12, 2014

Thank you for the confidence. I hope the book lives up to your expectations.

LikeLiked by 1 person

accidentallyreflective

September 14, 2014

Oh I know it will!

I just bought it! Looking forward to reading it 🙂

LikeLike

kasturika

September 14, 2014

Reading through your blog posts, one can never really know the challenges you have faced in your life… I can not even begin to comprehend what a challenge it must have been to write this down… It was heartbreaking to read through the post, and the comments. Wish you, and Allison joy and peace.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 16, 2014

That’s exactly the lesson I keep hoping I’ve learned — that we can never completely know what another person is going through. Thank you for your thoughtful comment, kasturika.

LikeLike

morristownmemos by Ronnie Hammer

September 16, 2014

Charles, congratulations on publishing this book. I heard about it on “She’s a Maineiac’s” blog. Since you are one of my favorite bloggers I look forward to reading it…although I don’t think it’s going to be a humorous book.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 18, 2014

There are humorous parts, Ronnie, but the overall story is a serious one.

LikeLike

7m

August 15, 2015

I will introduce my friends to read it. very nice! wonderful!

LikeLike

Transcend Fine Jewellery

November 10, 2015

This was so beautiful and so poignant, we are definitely buying your book!

LikeLike

Bonnie Bradley

August 14, 2016

I recently finished your book. I absolutely loved it. I loved your devotion to Jill even in the tough times, you never gave up on her, even though you had to make decisions which i am sure were very difficult for you to make.

LikeLike