When I was a kid, we called each other a lot of names. These names were not flattering, but neither did they reflect intense anger. Rather, they were meant to inflict momentary insult, often in response to a perceived slight, a physical injury, or an inconsiderate action. For example, if one of your friends smiled after spotting the thirty-seven at the top of your spelling test, you might tell him that he was a no-good rat fink. If he stepped on your foot or tried to cut in front of you in the milk line, you might call him a bonehead, or a blockhead, or pretty much anything that described his head as being composed of some dense material. If he made a ludicrous statement, like, “The pope goes to the bathroom,” you’d accuse him of being cracked, or crazy, or a stupid idiot.

When I was a kid, we called each other a lot of names. These names were not flattering, but neither did they reflect intense anger. Rather, they were meant to inflict momentary insult, often in response to a perceived slight, a physical injury, or an inconsiderate action. For example, if one of your friends smiled after spotting the thirty-seven at the top of your spelling test, you might tell him that he was a no-good rat fink. If he stepped on your foot or tried to cut in front of you in the milk line, you might call him a bonehead, or a blockhead, or pretty much anything that described his head as being composed of some dense material. If he made a ludicrous statement, like, “The pope goes to the bathroom,” you’d accuse him of being cracked, or crazy, or a stupid idiot.

And sometimes the verbal volley was just our way of saying hello: “Hey, you pathetic jerk, what’re you doing? Wanna read comic books?”

The point is, it didn’t really matter what you said, because they were going to ignore it anyway. We weren’t so afraid of words, and we weren’t easily offended. I suppose, without realizing it, we were focused on intent: if the person didn’t mean to hurt us, then we didn’t feel hurt.

One of the most popular television sitcoms of the 1950s – and of all time – was I Love Lucy. In the show, Lucy made fun of her husband, Ricky, who was a Cuban bandleader. She would imitate the difficulty he had when trying to pronounce certain English words, especially contractions, which he would shorten further to a single syllable. And she would attribute all kinds of negative traits to his Latin ethnicity, including a stubborn streak and a volatile temper.

It would be impossible to get away with something like that today. Protestors would picket outside the studio, while the actors and directors engaged in ponderous interviews, legal consultants offered in-depth analysis, and editorials called for somebody to be fired. The number of viewers who were disturbed, devastated, and emotionally scarred would grow by the day. Outraged politicians would compare the show’s dialogue to the brutal enslavement of Caribbean natives by Spanish explorers. A class-action lawsuit would soon follow.

Few observers would bother to mention – or even notice – that Lucy loved her husband, and that her harmless jokes were one way in which she expressed that love. Back then, the audience understood this, and no discussion was necessary.

I’m not suggesting that there’s any lack of evil behavior, or that language isn’t one of the tools employed to convey cruelty. But we need to make the distinction.  During and immediately after the second world war, when people referred to the Japanese as Japs, they were talking about opponents in an armed conflict. It was that adversarial role that gave the term its significance. On its own, Jap was simply an abbreviation, just as Brit was a shortened and endearing way to identify British soldiers and citizens, who were America’s allies. It was the feelings behind the names that gave them their meaning, and their effect.

During and immediately after the second world war, when people referred to the Japanese as Japs, they were talking about opponents in an armed conflict. It was that adversarial role that gave the term its significance. On its own, Jap was simply an abbreviation, just as Brit was a shortened and endearing way to identify British soldiers and citizens, who were America’s allies. It was the feelings behind the names that gave them their meaning, and their effect.

The latest controversy involves the National Football League and its Washington franchise. As it has in the past, the use of the word redskin has erupted once more in an explosion of indignation. Apparently, it’s a racial slur to refer to a group of individuals by their complexion, something most of society does routinely, and without great risk to civilization. I have to admit that I don’t like the practice, and avoid it whenever possible. But the words are an undeniable part of our culture, and while it seems inappropriate and anachronistic to call a professional sports team the Redskins, I imagine the name was chosen out of admiration. I’m sure it has, over the decades, engendered a sense of pride, as well. If it wasn’t intended as a slur, then it isn’t.

Racism is alive and well, everywhere. There’s no doubt about that. Humans are hard-wired in such a way that each group believes itself to be superior to others. At the same time, people are wary of those who look, sound, and act strangely. The results are never pleasant, and often gruesome. We annihilate each other by the thousands, sometimes for no better reason than that the gods we worship have different titles. We slaughter entire populations with a mindless sense of purpose, justifying our madness by pointing to the history books and explaining that this is what our parents did, and what they taught us to do.

Maybe it’s only a coincidence, but it seems that one day we put away our words, and replaced them with knives and ropes, handguns and automatic weapons. We stopped talking and started killing — almost always in the dark, under cover, or behind closed doors, in secrecy and quiet.

Now we find ourselves living in an age when moviegoers and shoppers are attacked without warning. Children are kidnapped from their schools or shot in their classrooms. Citizens of all ages are murdered by their own governments, or by the military paid to protect them. The stories come and go, moving onto and off the stage like a programmed slide presentation. And yet, we can’t stop talking about the owner of a basketball team — a pathetic, self-deluded billionaire — and his garbled ramblings. And we can’t get past the fact that some football players have that horrible name on the back of their jerseys.

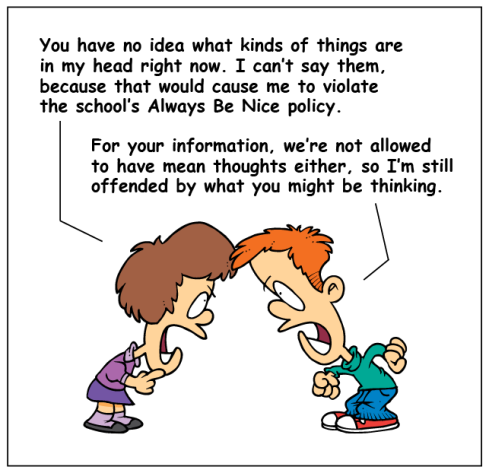

We need to distract ourselves. I get that. It’s much easier to clamp down on speech than it is to deal with violence. But the worst genocides are always accompanied by restricted communication and a general fear of self-expression, so reticence isn’t a healthy sign. I worry sometimes that we’re turning into a mass of quietly seething loners. We hold our words and thoughts inside, concerned about losing our jobs or offending our friends.

I miss those days when we were all just a bunch of pathetic jerks, blockheads, and stupid idiots. And we weren’t afraid to say so.

Noreen

June 27, 2014

I agree with you. It is ridulous that everything is so politically correct that just expressing an innocent thought has to be weighed and measured. I like what you said about intent. If it is not intended as a slur, then it isn’t.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 27, 2014

What really bothers me is that most of the people who pretend to be upset about the name Redskins are unconcerned with the real problems Native Americans face every day: crime, drug abuse, alcoholism, unemployment, depression, and suicide. They’ll force a football team to change its name and then go away, thinking they’ve accomplished something.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jennie Upside Down

June 27, 2014

I’m not pretending to be upset by the name “Redskins”. I always have been. Interesting. People will lose their minds over racial slurs, but apparently it only depends on who you are. It isn’t okay to call a Hispanic a “wetback” a Chinese person a “chink” and you can’t call a black person a “nigger”. We certainly would never have sports teams named after those slurs. But for years, it has been okay to call a football team in Washington the “Redskins”. Native Americans have historically been an invisible minority in this country. Those who do see them often plagiarize, appropriate and rip off their cultures. Add to that those that idolize them and see them in an unrealistic light. Native Americans are not a hobby. It’s almost as if they aren’t even seen as people. I’m glad the Washington Redskins lost their patent. It’s about time the issues are being heard. This is one step. I don’t know who took the poll stating that 90% of the native people in this country didn’t care. That’s not entirely true and I question the percentage. How many people did they even talk to? Were there studies completed to verify that person’s blood line. I mean really, I know countless people who claim to have their 3.8% someplace along the lines and their great grandmother was a Cherokee princess… We don’t want to hear all that, it probably doesn’t fit anyone’s narrative.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 27, 2014

I understand what you’re saying, but I don’t think the word redskin has the same connotation as those other terms you mentioned. To me, it just seems like a strange name for a sports team, not one that was intended to be offensive. I think most people put the word in the same category as white and black, which, again, are weird ways to describe human beings, but for right now that’s where we’re stuck. Also, I doubt the name itself produces income in the sense that anyone goes to the games because the team is called the Redskins. On the other hand, it’s going to cost the owners millions of dollars to change the name — new uniforms, logo design, stationery, marketing, souvenirs, signs, and many other things. Here’s a hypothetical question for you. How would you feel if the name remained unchanged, and the owners of the team instead donated those millions of dollars to a cause that would benefit Native Americans? Would that be enough to turn the situation around?

LikeLike

Jennie Upside Down

June 27, 2014

I actually disagree with you. The name is the same thing. I actually believe that people disregard the value because it’s in reference to the native people. Sorry, but I actually feel that way. There’s a very dismissive attitude that is alive and well. As far as your question, it’s a good one.

LikeLike

sonicspenny

June 27, 2014

this is awesome and so true with what’s happening these days

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 27, 2014

Thanks for taking the time to read it, and comment.

LikeLike

sonicspenny

June 27, 2014

no problem it was a good read 🙂

LikeLike

Hippie Cahier

June 27, 2014

If some no-good rat fink called me a “broad,” I would want to kick him in the shins.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 27, 2014

You’re much too young to be called a broad.

LikeLike

Ashley

June 27, 2014

This was brilliant, Charles. That’s all I got – well, that, and I’m definitely sharing this one:)

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 27, 2014

Thank you, Ashley. I’m glad you liked it.

LikeLike

Anonymous

June 27, 2014

Good blog, Charlie. Lots to think about. The Redskins should have changed their name years ago. You can’t name a team after a race of people, as if they’re some sort of mascot. If they were called the Welders, or the Computer Programmers, that would be okay. But the word Redskins is demeaning to Native Americans. Their skin is not red. If you’ve ever seen an old western, you know that the term “redskin” was usually preceded by an unflattering description. And if you’ve seen the Redskins play lately, you’d really be offended.

I think our generation is part of the great transition period that went from almost total insensitivity to what is called “political correctness” but what is really just sensitivity towards others. The term “political correctness” was coined by people who found it too difficult to watch what they said. Those people are dying out. My daughter’s generation is a very tolerant one.

As for your other point, people still express opinions, but it’s through the social media, such as facebook (or this blog), and not verbal. Yes, the news does give us a lot of coverage of bread and circuses, but that’s always been the case. The powers-that-be know that the less hard news we’re given, the less likely we are to question what they’re doing. But the truth is out there, if you really want to know it. it’s just requires research and the ability and desire to separate fact from fiction. And that’s easy. Whatever the mainstream media tells us, is fiction.

Allow me to end with some good, old-fashioned name calling: the owner of the Washington

Redskins is a pinhead.

LikeLike

Angelo DeCesare

June 27, 2014

Sorry, Charlie. I meant to identify myself. It’s me, Ang.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 27, 2014

You’re kidding, right? You could have said your name was Mr. Marshall and that you’re the president of the Gotham Bus Company, and I still would’ve known it was you.

LikeLike

Bill(y)

July 5, 2014

Is that because you’re the guy who brives the dus?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 7, 2014

When the smoke clears away, we’ll have ninety-nine thousand dollars!

LikeLike

desertdweller29

June 27, 2014

I love this line: “Maybe it’s only a coincidence, but it seems that one day we put away our words, and replaced them with knives and ropes, handguns and automatic weapons.” We can’t become a society so afraid of words that it empowers them in a negative way. Excellent and thoughtful post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

bronxboy55

June 28, 2014

Maybe it’s that we feel powerless to do anything about all the terrible things that happen in our culture, so we focus on the spoken word. Thanks for the comment.

LikeLike

Mikels Skele

June 27, 2014

Hmm. The Washington Mackerel-Snappers. Has a nice ring. Or Washington Dagos?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 28, 2014

But it isn’t just the reference to skin color, Mikels. It seems to be any reference at all. The Cleveland Indians and Atlanta Braves have been dealing with this issue for decades.

LikeLike

Mikels Skele

June 28, 2014

To me, the issue of no offense meant works only once, before you find out that offense was given. It’s one thing to call a kid something in a schoolyard, and quite another to keep calling him the same name after he takes offense, let alone putting the offensive name up in lights. And I think Indians, and even Braves, is much less offensive than Redskins, which really always was meant to be offensive. But then, it’s not up to me to decide, is it? Would you really be happy with a team called the Wops, even if they insisted they meant no offense?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 29, 2014

As I said in the post, I think the name is strange and inappropriate, but I don’t see how it’s offensive. When we refer to people as black or white, those words are inherently neutral. There are other terms for those groups that are derogatory, and therefore offensive. The word Wop is not neutral; it’s always been used in a degrading way. I think redskin is in the same category as Jap — it’s neither positive nor negative, but its meaning depends on context and intention. It would also be a strange name for a sports team. In the end, I don’t really care if they get rid of Redskin. If they do, the real problems will still be there, and there are very few people who give them a moment of thought.

LikeLike

Anonymous

June 27, 2014

Lets remove Washington from the name as I find that more offensive!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 28, 2014

I wish I’d said that.

LikeLike

ranu802

June 27, 2014

I love the way your post started with kids calling each other names, which was harmless, and slowly but surely you brought about what’s happening today, yes we are humans and we have very little patience or consideration for those who unfortunately look different and speak a different language or fail to pronounce accurately.

I guess when God put us on this earth, He wasn’t aware this would be the biggest issue.looking different, speaking differently, even He wonders whether Satan meant it when he said he’d make sure all this will take place.

We sometimes wonder was it wise to throw him out of paradise, one who was created with fire. I always enjoy reading your posts, they are so meaningful. Thank you.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 30, 2014

Thanks, Ranu. I always appreciate your feedback.

LikeLike

Doug Bittinger

June 27, 2014

Good article (as always). It does indeed seem that those who espouse tolerance and acceptance of all are the first to try to kick your face in if you say anything they think might offend someone somewhere. I think it’s a sign of deep-seated insecurity, myself.

LikeLiked by 1 person

bronxboy55

June 30, 2014

As I see it, there’s always going to be someone who’s offended by something. So the real question is, where are the boundaries, and who gets to decide? It’s easy to start with the obvious, but when does sensitivity become intolerance?

LikeLike

Margo Karolyi

June 27, 2014

“Sticks and stones may break my bones, but names will never hurt me.”

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 30, 2014

My father said that all the time. Not really true, as I eventually learned — words can definitely hurt. But I’d rather cope with that pain than live in a society that muzzles its citizens and stifles free speech.

LikeLike

Kathryn McCullough

June 27, 2014

Another great — or should I say “pathetic-loser” of a — post! Seriously, I totally get what you are saying. Don’t we have bigger fish to fry—-no offence to the fish.

Hugs from Ecuador,

Kathy

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 30, 2014

You’re such a troublemaker. If I get any comments from offended fish, I’m forwarding them to you.

LikeLike

SomeKernelsOfTruth

June 27, 2014

You bring up a lot of interesting points…today, society is often misguided as to what we should be focused on and worried about. Thanks for sharing this interesting perspective.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 30, 2014

I think we need to pay less attention to words and more attention to behavior. There are a lot of people — and corporations and governments — saying all the right things. But their actions tell a different story.

LikeLike

SomeKernelsOfTruth

June 30, 2014

Very true.

LikeLike

simonandfinn

June 27, 2014

Beautiful post.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 30, 2014

Thanks, Melissa. Have you done a S&F strip about this topic?

LikeLike

simonandfinn

June 30, 2014

I haven’t actually. It certainly is thought-provoking though.. maybe I will muse on this and see if I can come up with something –

LikeLike

Dounia

June 27, 2014

Great post and so eloquently written (as always). I’ve often commented on the absurdity of everything needing to be “politically correct” and the way people get into uproars over silly things thinking they’re making a statement (i.e. the Redskins issue or the Donald Sterling one with NBA)…But we seem to forget the real problems and trying to find real solutions. Thanks for writing this and sharing it – if only more of society thought like this and did something about it. Maybe then we could get on the right track and make a difference where it matters.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 30, 2014

I guess if the ensuing uproar produces some positive results, then it’s worth all the chest-beating. My concern is that we tend to get caught up in patching the surface, rather than fixing the underlying problem.

Thanks for the kind words.

LikeLike

The Sandwich Lady

June 27, 2014

In the blue collar neighborhood of my youth, our Irish neighbor Andy O’Toole called my dad “Waldo” (which was considered a slang word for Italian people at the time), and my Dad lobbed back with “Mick.” In between our two front porches (where the lobs were launched) was our bemused Welsh neighbor, Mr. Shillingford. It was all done affectionately and we were always there to support each other — the only thing that mattered. Great post and loved the cartoons too!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 30, 2014

I’d never heard the term Waldo before, Catherine. I think I’m a little outraged.

LikeLike

genusrosa

June 27, 2014

You tackle a sensitive issue very thoughtfully, thank you for this post. It is so true that intent is the chief driver of offense; that goes for childish insults, as well. While blockhead or numbskull might be grown out of and laughed at later, mean-spirited insults like pizza face, fatty fatty, four eyes and I’ll stop there because I know they get worse (well…’chicken neck’ was particularly hurtful to me :o))…shows a young mind already at work at deriving insults that are meant to hurt in specific, humiliating ways. This type of littleness grows up into the bigger world, where then racial slurs and downgrading speech become their commonplace talk. Unfortunately, these things are learned chiefly at home, from parents who should know better. But they can be unlearned. As parents, or adults, it is our responsibility to ‘know better’. It’s up to all of us to do our part to create a kinder world, where everyone who wants to can thrive.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 30, 2014

I’d never thought about it like this before, but maybe exposure to insults builds up the emotional immune system in some way. No matter how much we wish for a kinder world, it can be a pretty insensitive place. It helps to have the ability to discern the difference between harmless and harmful. That applies to mushrooms, snakes, and words, too. At least, that’s what I think.

As always, I appreciate hearing from you.

LikeLike

vgfoster

June 27, 2014

Bravo! Great reminder that we all need to relax and not take everything we hear personally.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 30, 2014

I agree — although it is easier to do that when we’re just observing, and not the ones in the line of fire.

LikeLike

Patti Kuche

June 27, 2014

Did I hear they were re-naming the team the Ronald Ray-Guns?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 1, 2014

They’d better hope the referees are all Republicans.

LikeLike

subodai213

June 27, 2014

I found that, as kids grew up, the name calling became less ‘affectionate’ and more a form of verbal bullying. The old phrase about “names will never hurt me’ is wrong…being called Fatso or Four Eyes by a peer and everyone taking it up is bullying, pure and simple. One doesn’t need to have bruises to feel pain.

But you are absolutely correct-racism and exclusiveness are innate. We ARE hard wired to be xenophobic, to fear and distrust the person who doesn’t look, sound, or seem to be like us. It’s what drives tribalism, and let’s be honest, just because we’re not running around with sharp rocks on wooden sticks, we’re still tribal. We’ve merely changed the weapons to guns and the tactics to war and genocide.

As for the name of the team: I was a big fan of the Skins for years, especially when they beat the Cowboys. I’ve not watched football for years, so I don’t know how they do now, but even then, the name Redskins bothered me. I’m white American Mutt, so I have no emotional or self imaged interest in the word, but….the owner needs to change the name. Imagine if a basketball team composed solely of black men were to be called “The Darkies”..oh my god. (or a basketball team composed solely of white men called the “Can’t Jumps”.)

Nope, the name of the Redskins needs to change, to something animal, and something regional. “the Washington Blue Crabs”? The Chesapeake Bay Retrievers?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 1, 2014

I’ll be surprised if the name goes unchanged for more than another season or two. And after that, Native American issues — the real ones — will fade back into oblivion, until the next superficial controversy gets everyone riled up.

I think the “D.C. Current” should be their next name. Or is that redundant?

LikeLike

subodai213

July 1, 2014

Well, that is redundant, but given the Washington moniker, maybe the team name should reflect the realities of that city: The Washington Partisans. The Do Nothing Congressmen. Ahhhhhhhhhhhhh I have it. I have it. The Porkers.

LikeLike

O. Leonard

June 27, 2014

I don’t think we need to change the name of the Washington Redskins. I agree with you that it won’t change anything, and completely ignores the real issues of Native Americans. You might find it interesting that not all indigenous people agree with that term either. Naming the Redskins the Redskins was not an ethnic slur. The team originated as the Boston Braves in 1932. Changed to the Boston Redskins and then relocated to Washington in 1937. I have to think that the name was chosen to indicate strength. Just the like the Bears, and Giants, and even the Packers. Other original NFL franchises. Aren’t the Cincinnati Browns one step away from referring to an ethnic group? The whole controversy, which isn’t new, is a waste of time and effort that clearly could be used in more important ways. On June 18, 2014 the United States Patent Office voted 2-1 to cancel the trademarks of the team. Now everyone can use the term Redskins. Seems kind of pointless.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 1, 2014

Whenever one of these issues comes up — and there’s always something to get us arguing — I move away from the original point, and wonder where the line is. I asked this about the ban on peanut products in many schools. What if there’s a child somewhere who’s deathly allergic to bread, or milk? Or pencils? When individual rights bump up against group rights, how do we decide what to do? Let’s say they get rid of the Redskins name. What might be next? The word Yankee is considered a derogatory term in some places, and so is Canuck. Will very tall people say they’re offended by the Giants and Titans? And why are we glorifying Pirates and Devils?

At some point, it gets ridiculous. The question is, where is that point?

LikeLike

Jac

June 27, 2014

Political correctness has run amok. I guarantee that most of the folks who are upset about the Redskins name have no native blood in them. They do it to make themselves feel good about themSELVES. The names that teams chose long ago. reflect the attitude that they thought these people or animals were winners! We have parks and rec baseball teams in our town, and every year they choose different names, based on MLB teams. Now there is one team that comes from a nearby town, which is an Apache reservation. Every kid and their coach, is from the Jicarilla Apache tribe. Do you know what name they use EVERY year? The Dulce BRAVES.. They are proud of the name and obviously don’t find it offensive.

BTW – My friend’s son came up with a great solution to this problem, Keep the name Redskins and just change the logo to a potato. Sometimes, you just have to laugh about this stuff…

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 1, 2014

When Shaun started playing organized baseball, his team was the Mosquitoes. There were the Tigers, the Bears, the Hawks, and the Mosquitoes. They were pretty intimidating. They couldn’t score runs, but they’d leave you with little red bumps all over your kneecaps.

LikeLike

Jac

July 1, 2014

So I assume that the best hitter on the team was known as the Sultan of Swat? 😉

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 2, 2014

I set you up for that. I didn’t see it coming, but I still set you up.

LikeLike

LeighMcG

June 27, 2014

Awesome. Couldn’t agree more!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 1, 2014

Thanks, Leigh. It’s good to hear from you.

LikeLike

thomascmarshall

June 27, 2014

There is a fear of history repeating itself when, as a society, it forces people into a corner so they cannot express themselves without fear of retaliation. The end result is no expression at all, especially when it’s needed. Humans are truly amazing, and incredibly stupid.

Can I say that?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 1, 2014

You can say it today, Tom. But tomorrow may be another story.

LikeLike

raeme67

June 27, 2014

I was a pathetic jerk once, but I graduated to mediocre adult. Great post, as always.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 1, 2014

That’s a big step, Rachael, going from pathetic jerk to mediocre adult. I’m still working on it.

LikeLike

raeme67

July 1, 2014

😀

LikeLike

morristownmemos by Ronnie Hammer

June 27, 2014

I’m sorry that I cannot respond; I’ve got post traumatic stress disorder and can never function again. Not to mention the suggestion that I go back to work. Injured forever.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 2, 2014

Sounds like you’ve been insulted and offended.

LikeLike

rangewriter

June 27, 2014

You raise some interesting and thought provoking notions, as always Charles. I was under the impression that pushback regarding the name of the team originated with native Americans. I could be wrong about that. It’s not a subject I follow.

I suspect you are right in that originally, the name Redskin probably evoked a sense of fear, power, and prowess. However, Indian Nations in this country have fallen so far below the original power and dignity they had (for reasons mostly defy humanity) that I’m not certain the moniker illicits much in the way of respect these days.

To me, however, the bottom line is how does this team name impact our native peoples? In Idaho we are dealing with similar issues, mostly related to geographical monikers. Squaw Butte, Indian Creek, etc. I don’t see many place names like Honkie Hills or Haole Heights. Nor is it okay to say Nigger Creek or Nigger Toes. So, if we must inconvenience ourselves to rename or whitewash (!?) a few institutional names, I’m ready to go with the flow.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 2, 2014

But is it just a few? Once we start bleaching the history out of these names, where do we stop? Maybe in the future, everything will just be numbered. It seems to me that a lake with a name like Huron or Great Slave might induce someone to become curious, and maybe even learn something. I think when we try to erase past wrongs, we risk blinding the next generation to the mistakes we’ve already made. And isn’t progress an accumulation of lessons?

LikeLike

rangewriter

July 4, 2014

I get your point. But I think instead of illiciting curiousity, we simply become innured to an ethnic slur, just as young girls become desensitized to sexually demeaniing images that objectify their femininity.

LikeLike

thecontentedcrafter

June 27, 2014

Well said sir! Let’s focus on intent in all realms of life – let’s start with ourselves and our own intentions and take responsibility for what surrounds us. And then lets always remember that anything anybody else says about us says more about them. Fear is, in my experience only I admit, the greatest motivator for political correctness, litigation, racism, sectarianism and probably any other ism you care to name. Education should focus less on ‘jobs’ and more on the humanities [again, just my opinion]. Imagine a world when after you’ve finished being a rough and tumble kid you actually have an understanding of and empathy for all cultures, nationalities, spiritual persuasions and a desire to travel the world and contribute where your talents best lie………………. Oh well, I’ll settle for letting kids play outside in all weathers for now.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 2, 2014

Equally well said, Pauline. There would be a lot less reason to be offended if we all took a little more care in the way we treated others. It’s just a matter of shifting our focus — from looking for trouble out there to fixing what’s wrong in here. Easy to say, of course.

LikeLike

earthriderjudyberman

June 27, 2014

I had a co-worker, who was Mexican-American, and he thought Ricky Ricardo was an embarrassment to Latinos. I tried to tell him that Ricky was adored by all the females I knew – both young and old – and Lucy was the buffoon. She was always scheming to be part of his band.

On the names that are bandied about, well … sticks and stones do break your bones and names can hurt you. While we might have gone too far in the P.C. language, I think it’s more important how we act toward one another – not fake, but for real. If we take into account the Golden Rule – to treat others as we’d like to be treated – then we might not have the violence and wars that we do. I realize that’s an idealized outlook. It might be worthwhile to look into it and model it. 😉

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 2, 2014

Judy, I agree that names can hurt. Anyone who says that words are harmless is ignoring the fact that the right words can fill us with happiness. But human beings get angry, and some of us dislike each other, and we have words for expressing those things, too. I think we need to be careful about trying to deny that. War is madness, but at the other extreme, universal love would require mass sedation.

LikeLike

Ruth Rainwater

June 27, 2014

It may not be a huge problem in the great scheme of things, but I thought we had evolved enough as human beings to take into account that words can hurt. I guess I was wrong. the original intent may have been to honor a race of people, but I doubt it. Using racial epithets is no way to honor anyone. Just because Redskins was okay back in the 40s and 50s doesn’t make it okay now. Just because calling me ‘girl’ or ‘broad’ was okay in the 50s doesn’t make it okay now. Times change, and so should we. It’s the same as someone having a difficult-to-pronounce name and the teacher or boss or whoever saying the name is too difficult so I’ll just call you Jim. It’s taking away or denigrating a person’s identity.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 2, 2014

Ruth, I’m not defending the name Redskins, nor am I advocating that the team keep it. In fact, in this post I called it inappropriate and anachronistic. But at the same time, I can’t help but remember that NAACP stands for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Colored people! No one starting an organization today would even consider using such a name. But it’s been around since 1909, and I’ve never heard anyone demand that it be changed. That’s because, while the phrase colored people has all but disappeared, its continued use by the NAACP is justified by the original intent, which was constructive rather than racist. However, I have a feeling that in the case of the football team, you’ll see a new name in the next few years.

LikeLike

Dennis Wagoner

June 27, 2014

Great post. Political correctness is always a distraction from the real problems. Rename the Washington team and where does that get to resolving the real issues facing Native Americans today? The answer is between no where and farther behind.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 3, 2014

People will feel they’ve accomplished something tangible. It reminds me of how we neglect war veterans, then build expensive monuments to honor them.

By the way, your comment ended up in the spam folder. I found it this morning.

LikeLike

Elyse

June 28, 2014

Brilliant, Charles.

I live in “Redskins” territory. And you are sooooo right, I bet if I polled a group of folks, nobody would be able to tell me what tribe of Indians lived here (is the word ‘Indian’ the next taboo?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 2, 2014

The word Indian has shown surprising endurance, Elyse. What it really says is that the Europeans had powerful weapons, but their geography wasn’t so good.

LikeLike

icedteawithlemon

June 28, 2014

There are no easy answers, are there? I agree with your point that we should focus on the intent behind the words, but I also realize that too often the speaker’s intent is “lost in translation,” and the listener is too easily offended when no offense was intended. And, like you, I worry that too many are becoming “quietly seething loners” because they are being encouraged (by the media, by parents, by society) to be offended rather than being taught the coping skills necessary for dealing with slights, real or imagined. And I don’t know if that even makes sense …

And as for that ” pathetic, self-deluded billionaire,” even more disturbing than his private-conversation ramblings was the amount of media coverage given to his words. As you pointed out, we have much more important things to worry about it

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 2, 2014

Speaking of media coverage, radio host Don Imus was fired a few years ago for saying something stupid about a women’s basketball team in New Jersey. Here’s a guy who’s paid to be shocking and outrageous, and was dismissed for doing just that. His original remark was insensitive and not funny at all, but it was a two-second blip in a long stream of nonsense. I’m sure it would have gone unnoticed by most of his audience, and obviously missed by anyone not listening to him. But the resulting outrage ensured that everyone in the country heard the bad joke, over and over. And so hurt feelings were caused, magnified, and repeated — the very opposite of what the censors were trying to do.

LikeLike

icedteawithlemon

July 2, 2014

I was not a Don Imus listener, but I remember that incident–and I remember being outraged by it, without realizing at the time that the media had manipulated me into having such strong feelings. When I was a journalism student years ago, I remember being taught that the main functions of journalism should be to inform, educate, entertain, and to enable decision making. I’m sure there were other purposes listed, too (it was a LONG time ago), but I don’t remember ever being taught that the purpose of journalism (in any form) was to incite–which too often now seems to be the MAIN purpose.

LikeLike

Angelo DeCesare

June 28, 2014

Wow, Charlie. It’s amazing how many of your posters just don’t get it. Please let me attempt to explain this issue one more time:

1. The NFL has 32 teams. Only one is named after a race of people. The Vikings are not a race. They were Caucasian Scandinavians from a particular era in history. To make their name controversial, they would have to be called the Whiteskins.

2. One of your posters referred to the “Cincinnati Browns”. There is no such team. If he meant the Cleveland Browns, they were named after the team colors. The equivalent of the Redskins situation would be calling a team the Brownskins. If you think that would be acceptable, then stop reading here a have a nice day.

3. Intention is irrelevant. The people who named these these teams were not Native Americans. Nor were the owners, coaches, players and the majority of their fans. So the actual Native Americans were not given a choice in the matter.

4. Finally, unless you’re a Native American, you don’t get to say that the name Redskins is acceptable. If a number of Native Americans are offended by the name, and they are, than it is morally and ethically correct to change it. This is not political correctness. This is a clear case of right from wrong.

LikeLike

O. Leonard

July 1, 2014

Sorry about the typo, obviously know they are the CLEVELAND Browns, but you want to do some research, they weren’t named after their colors. Many believe they were named after their first head coach, Paul Brown, but history says they were a shortened version of the “Brown Bomber” the nickname of boxer Joe Louis. Their colors are burnt orange, seal brown and white. They should have been the Cleveland Oranges. And, you’re right, I don’t get it, but it is not a clear case of right from wrong by any stretch.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 2, 2014

But intention is relevant. There are many gestures that we use every day that are deemed rude and offensive by other cultures. Should we ban those gestures because someone interprets them differently? Anyway, they’ll likely change the name of the team soon, and then we can move on to the next item on the list, whatever that is.

LikeLike

subodai213

July 3, 2014

Amen!!!

LikeLike

walt walker

June 28, 2014

We live in an incredibly hypocritical world. People espouse freedom of speech and the right to say whatever they want, whenever they want, until it touches the hot button of the moment. We can say the nastiest, cruelest things possible about religion, for example, but we can’t say anything that might be even remotely construed as possibly negative about a gay person. Black comedians can make fun of white people but white comedians cannot make fun of black people. That’s not freedom of speech. (Not to mention that that’s not even the kind of freedom of speech we should be talking about when we talk about Freedom of Speech).

That said, the name “Redskins” should certainly go.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 2, 2014

Thanks for your input, Walt. I hope that a hundred years from now, people will look back on our time and be at least slightly amused by our preoccupation with relative skin color. I’d also like to be around to see it, but that’s another story.

LikeLike

Jennie Upside Down

June 28, 2014

I’m not trying to start a fight… I am curious though. If referring to a Native American individual as a “redskin” is okay… Then I shouldn’t worry about being “politically correct” when referring to another ethnicity. So, moving forward all Chinese people are Chinks, Hispanics are wetbacks and Blacks as niggers and so forth. That’s exactly the message that I am getting from people. I think the term “politically correct” is being thrown around a bit much in this case. Like I said above. I think that this has everything to do with the group of people being referenced. Silent minority. I do not and never will understand why people aren’t seeing this.

Sports? Doesn’t fit their narrative? Neither does history.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 2, 2014

Jennie, I understand what you’re saying, and I also realize that the issue doesn’t affect me as deeply as it affects you and others. But I think it’s important to recognize that certain terms are clearly meant as slurs, while others are not inherently negative. When I was a kid, it was an insult to be called a Jew. We knew nothing about Judaism, but if someone used that word, they weren’t trying to flatter you. Now that I’m an adult, the word Jew has no negative connotation, so its ability to cause hurt has been eliminated. For me, the word Redskin is equal to the words Black, White, and Jew in that it’s emotionally neutral. I would have to search for the meaning behind the words in order to determine what the speaker was really saying. And I can’t imagine a professional sports franchise choosing a name that intentionally insults anyone. It isn’t that I don’t know there are Donald Sterlings sitting behind big desks and thinking stupid thoughts. But these people are in the business of attracting customers, not repelling them. So while I believe Native Americans have a long list of legitimate grievances, in the scheme of things, I have to wonder if spending more time and energy on this issue is really worth the trouble. But again, I’m not in the middle of it, so I don’t really know.

LikeLike

Jennie Upside Down

July 2, 2014

Like I said before, this was one step towards the bigger issues. Native people are a silent minority. Not hardly seen as people which has really been proven with this issue.

LikeLike

D Holcomb

June 28, 2014

Like you, I’m nostalgic for the “good old days.” That said, when I think of some of the comedy then, like the three stooges–I just don’t get the humor in cracking someone over the skull. Or the racist jokes that Sinatra made about Sammy Davis Jr. (who was offended by them, altho he went along with it at the time). I’ve gone over the line with my humor at times, not meaning to offend, but succeeding in doing so. It’s a fine line. But you’re right, the intent behind it is key.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 3, 2014

Social comedy seems to get stale with time, and at some point the humor disappears. We end up either shaking our heads in confusion or just cringing. But if you listen carefully to a wide range of comedians today, you’ll notice that some performers can get away with pushing the edge, while others can’t. To understand why that is, you have to step back and listen to everything they’re saying. Then you can get the intent behind the words. I think most people operate on this intuitive level.

LikeLike

Personal Concerns

June 28, 2014

I greatly enjoyed reading this very well written post MBI! We are increasingly becoming a generation that is trained most in the nuances of political correctness. Language and bodily gesturing that comes naturally to us needs to be checked always. That in fact is one of the aims of sophisticated socialisation and education. To what extent should this education lead us to behave in ways that would count as fake is unclear to me. Your post does offer some insights and hence is surely some great food for thought. Regards!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 3, 2014

Doesn’t it seem as though there’s a direct correlation between the undercurrents of private hatred we keep finding and the way we punish anyone who says something that’s deemed socially offensive? I think trying to clamp down on speech is just making it worse.

LikeLike

Personal Concerns

July 3, 2014

Oh! I so admire the way you put it. That is so very true. I don’t know if you have seen the film “Little Children”. Its an average film I wud say but the essence of what it has to convey is very much in line with the correlation you are positing!

LikeLike

shoreacres

June 29, 2014

Just so you know, now they’re going after the Army, claiming that “Apache helicopter” is offensive to the Apache tribe. Whether the offended are Apache, I’m not sure.

I have had it. I have had it most of all with the term “politically correct.” Who defines what is and isn’t correct? If you don’t like what I say, you can stop reading my posts, or stop inviting me to dinner, or rake me over the coals at the next City Council meeting. But I have HAD it.

The trick, you see, is to censor by inculcating enough fear that self-censorship begins. That’s what dictatorships do. We’ve got entire segments of society incapable of resolving problems because they’re terrified of being honest. Too many of us constantly are looking over our linguistic shoulders to see if the thought police are on our tail.

To be quite frank, I find the common use of f— and c— and other such words just as offensive as anything in our lexicon. But, it seems to be the way of the world. So. What should I do? Pitch a fit and demand that the rest of the world stop using crude language? . Personally, I prefer to leave people alone with their freedom to be obnoxious, and go on and live my own life. And while I don’t use many of the terms that are considered inappropriate today, they left my vocabulary through education, experience and free choice. Not coercion.

If I could suggest anything, I’d suggest a reading (or re-reading) of “Animal Farm,” “1984”, and “Fahrenheit 451” for everyone. We’re there. The only questions are how many recognize it, and how many are willing to put themselves on the line to do something about it.

Now, as for those younger years… We grew up on a steady diet of “Fatty, fatty, two by four, can’t get through the bathroom door” and “I see London, I see France, I see Susie’s underpants.” Personally, I was known as Four Eyes for a year after I got my first glasses. Did we survive? Of course. And in fact, we learned more than we could have in a bubble. I ran home from school one time, upset about being called Four Eyes. Mom asked, “Do you have four eyes?” I said no. “Well,” she said, “that just proves they can’t see.”

LikeLike

shoreacres

June 30, 2014

I just bumped into a George Will column on this topic that’s a little longer on facts and analysis than my comment. It really is pretty interesting. I think you’d enjoy it.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 3, 2014

I think the term politically correct must have come from the tendency for politicians — especially those involved in a campaign — to modify their message according to each audience. It was easier to get away with that before radio, television, and the Internet. Now, exposed to the dire consequences of uttering something inappropriate or changing your mind on an issue, the only recourse is to speak in rehearsed fragments while saying nothing at all.

There’s a copy of Animal Farm around here someplace. I just hope it isn’t on the banned-book shelf. Meanwhile, thank you for the link to the Will column, and for sharing more of your Mom’s wisdom. I think I would have liked her.

LikeLike

subodai213

June 29, 2014

There’s a truism that history is written by the victors. Today, while there is a definite atmosphere of ‘political correctness’, it is the societal pendulum swinging wide to the other side of a demeaning ideology describing anyone who wasn’t white Anglo-Saxon Protestant. I am a quarter Polish and grew up hearing “Polock” jokes. Being a child, I began to believe that Polish folks WERE unwashed, stupid, beer swilling morons.( I even had an uncle who fit the stereotype perfectly.) I grew ashamed of what I had absolutely no control over. On the other hand, I grew up in a predominantly Catholic neighborhood, so I heard jokes about blacks, about Jews, about women, and all made the same point..that the person being joked about was less than human, and that the joker was superior. Calling a team the “Redskins” may originally have been considered an honor, but the very idea of it dismissed them as a group of humans, and became merely a set of characteristics that the namer may have admired. Did he actually have any Native Americans on the team? Ever?….Native Americans didn’t play football. And there’s been an extremely long history of the American government considering a Native American a ‘savage’, something to be exterminated. Ask Custer, who found out the hard way that sometimes, genocide backfires. There’s even a line in the Declaration of Independence, saying that the English Government had purposefully incited the ‘savages on our borders’ to attack Americans.

As for the cost of changing the name, logos, etc……..well, I’m not going to worry my Polish/German/French Canadian head about it. That poor pathetic billionaire can probably afford it.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 3, 2014

History is definitely written by the victors, and in the case of North America, the native people lost. They were pushed off the land, killed in battle, and most of all, wiped out by disease. In some form, that’s probably the history of every country on earth — people on the move encountering those who were already there. Inevitably, the lives of the losing side are degraded. I’m just not sure that changing the name of a football team is going to solve anything. It may be hailed as a victory, but if that’s all that happens, it will be a hollow one.

LikeLike

subodai213

July 3, 2014

Unfortunately, you are right. I like your idea of the owner of the team funneling money to tribes-but he didn’t get to be a billionaire by being a philanthropist. I don’t think that changing the name of the team to something less racist will change anything. But I do find it encouraging that people, most of whom are NOT Indian, are actually thinking that the name Redskin isn’t right. Nor do I agree that doing so makes me ”’feel better about myself”. That isn’t true, either. To simplify it, let’s just say the name isn’t nice. Like mom used to say, ‘if you can’t say anything nice, don’t say anything at all.’ I hear the testosterone fueled reaction to this. No, no one wants a team called the Pink Ladies or the Sissy Football Players. I get the aggression. I get the ‘dangerous men’ feeling. As one respondent pointed out, there are teams named after aggressive men: Vikings, Raiders, Buccaneers…but somehow, not Braves?

I dunno. It gets thicker and chewier as I type.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 5, 2014

The Braves play baseball in Atlanta. That team started in Boston and has been around for more than a hundred years. Coincidentally, I think the Redskins were also called the Boston Braves before their move to Washington. By the way, as an honorary Detroiter, I hope we’ll always have the Lions and Tigers.

LikeLike

subodai213

July 5, 2014

Charles, I am sorry to tell you this, but…you really want to root for a football team that wins…at least ONCE in a while. While I think the Lions have one of the three best helmet logos in the country (the other two are the Vikings and the Rams), the Lions..well, the Lions are really pussycats. Nice guys, always willing to let the other team win.

LikeLike

reneejohnsonwrites

June 30, 2014

Most things roll right off my back. However, as a woman in the south, I’ve felt insulted by the masochistic manner in which men sometimes address their female coworkers as ‘honey’ or ‘dear’ or some other non-professional term. So although I can’t speak for Native American terminology and its rancor for them, I will respect their feelings. Great post.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 3, 2014

See, this is what I was trying to talk about. When a man calls a female coworker ‘honey,’ his message is a condescending one. Or at least that’s been your experience. But when a woman addresses a male customer in the same way, there’s almost never any offense taken — because there was none intended. It isn’t necessarily the words, but the meaning behind the words.

LikeLike

Bruce

June 30, 2014

A really good read Charles. I’d like to know what the team members and their fans think? They seem to be the ones that count, or at least the native Americans amongst them. Wouldn’t they have dropped the name long ago if it offended them?

Being from Oz I know little of the sport scene in your part of the world, but have heard the name Redskins before. Funny thing, I didn’t automatically think of Indians, just the name.

I think you have something there when you say words were one day exchanged for weapons; I also think Walt Walker makes some very good points along with the rest of those who commented. So many good comments with different conclusions.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 5, 2014

It’s a pretty hot topic again, Bruce. I think it may stick this time, although other than the commenters here, I’m not sure who’s offended and who isn’t.

LikeLike

Bruce

July 5, 2014

If I reverse things a little and I played for a team called Whiteskins, I wouldn’t give a toss. After all, I think that’s supposed to be my colouring or origin and a sense of humour doesn’t hurt. But I suppose some will say that if a team was called Whiteskins then it probably represents some white supremacist group. You mentioned intent; that’s what it’s all about to me.

In Australia at the moment we have a Youtube video gaining momentum. It’s of an Aussie woman ranting and ridiculing Asians on a train. It’s also on news channels etc. and the police have been involved.

I don’t know her story but the comments on the Youtube are rolling in.

Amongs those condemning the rant are supporters of this woman, calling for whites only in Australia.

Racism, alive and kicking in this part of the world; just needs a good excuse sometimes for a good airing.

LikeLike

bardalacray12

June 30, 2014

Reblogged this on bardalacray and commented:

true that but< like the beginning, 'when i was a kid'. no more

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 5, 2014

Thank you.

LikeLike

KL

July 4, 2014

Great post as always. Name calling is something that we had to stop In our house not for political correctness but because our son takes everything very literally. With aspergers and autism on the rise now it’s really easy to offend someone because they just don’t understand. We are big users of “doofus” in this house, but we had to really teach our son that it was meant in total jest and loving intention when he did something we thought was silly but cute.

I love the connection you made to physical violence being a new way of expressing those thoughts that people are no longer allowed to say, it’s a very interesting point in light of the difficulties faced in your country that we don’t really see here in OZ. Sure we have people who say awful stuff to each other for real, but mates still slur each other in a loving friendly way without the fear of it being misunderstood.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 5, 2014

I think most people know the difference between friendly kidding and hurtful intent. But one by one, legitimate words are being eliminated from our vocabulary. Where will it end?

LikeLike

Bill(y)

July 5, 2014

Have not been to this blog in about a year.

Saw the mention of “Jap”. Here in Singapore, they love things Japanese – food, manga, cosplay, culture, etc. Japan is seen as the utlimate Asian nation, to which the others wish to progress to, but that is a topic for another time….. So, they refer to this food they love and revere as “Jap” food. On forums and whenever hear it in public, I point it out that it’s a racial slur. The the room gets quiet……

I’ve had a few internet forum mudslingings on this, mostly with Westerners who actually get it and don’t use the words themselves, although some to play the advocate, put up flimsy counter arguments, which peter out in the end as I cannot be beat at that game. Nothing against the Peters in the world……

Of course, like Garfield’s dog, they (the Singaporeans) do it innocently, but ignorantly. But I contend that ignorance doesn’t excuse it, and it certainly doesn’t validate perpetuating it. And so I remind them…

….just like I did the guy wearing a historically-accurate red shirt with a Nazi swastika on it (not an Asian “good” swastika, which goes the other way from the Nazi one and usually means an Asian temple).

Kid you not – I saw that same shirt twice in Singapore, both times worn by young locals in their teens or 20s. I told one how offensive it was, the other, like most of the too numerous to mention numbskull things that happen here, I just shook my head at him and kept walking.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 7, 2014

I still say the whole problem with “Jap” is its historical context. Had the Japanese and Americans been on the same side in the war, the term would have been used with affection, as “Brit” was and still is. Obviously, Singaporeans have their own perspective. The Nazi clothing is another matter entirely. I wonder if those people have any idea what they’re advertising.

How long have you been living in Singapore?

LikeLike

Bill(y)

July 7, 2014

Charles – we’ve had this conversation before, 10 years now, making it almost a quarter century being out of the US.

Agree with the anomaly of Brit, plus Brits call themselves Brits, Japanese would never, ever use that other term for themselves.

The Singaporeans are very book smart, but very street dumb, almost across the board. Hence the Garfields dog analogy. The Nazi thing, well, most Singaporeans are way smarter than that, that is just some misguided utes thinking they are hipsters without knowing the historical context.

LikeLike

clburdett

July 6, 2014

front page read! 🙂 gets the wheel turning

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 7, 2014

Thanks for the feedback. It’s always good to hear from you.

LikeLike

Bill(y)

July 8, 2014

Just a little surprised no one caught the ute thing….thought this was the right audience

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 9, 2014

Yoooottths.

LikeLike

hya21

July 8, 2014

You are so right. I only remembered Lucy’s tendency when you mentioned it, but we have become so thin-skinned and quick to take offense when someone expresses an opinion different from ours. What? You don’t like me? You know that means war!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 9, 2014

There has to be some healthy balance somewhere between being a doormat and letting every little thing hurt our feelings. I guess the problem is that the balance point is different for each of us.

LikeLike

Philster999

July 8, 2014

Not always the easiest subject to deal with — but deftly handled, as always.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 9, 2014

Thanks, Phil. I appreciate that.

LikeLike

marymtf

July 14, 2014

I’m sort of torn, Charles. I also yearn for the days when we weren’t so hamstrung by political correctness. Then again, I remember that Australians have been calling British people Poms for years and I’m sorry to say that it wasn’t meant affectionately and sorrier to say that it was only rectified quite recently.

Is it too late do you think, to find a happy medium?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 16, 2014

Mary, I worry that if we eliminate all of the offensive terms from our vocabulary, then everything else moves up a notch, until there’s a new set of words or expressions that are now the most offensive. Then we have to get rid of those. And it keeps going until we’re left with nothing but bland, pleasant-sounding language. The other problem is that the original thoughts are still there, only without the freedom to say them out loud. Won’t some of those stifled ideas eventually turn into something even more unpleasant — like violence?

LikeLike

silkpurseproductions

July 16, 2014

Can I get an “amen!” to that? I do think we have taken “political correctness” a tad too far. I am not for insulting anyones race or culture but I am pretty sure that at the time this team chose to call themselves that they weren’t even considering it an insult of any kind and chose the name in a more admiring kind of way. In the end all they have to do to keep the name is change the logo from a brave warrior chief to a peanut and then only the nuts will be offended…wait a minute…

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 19, 2014

Ottawa’s CFL team is called the Red Blacks, and Edmonton has the Eskimos. It’s only a matter of time before somebody becomes outraged.

LikeLike

nandininautiyal

July 27, 2014

hello! i am a 13 year old girl and i’d really love it if you’d just come and see my blog! comment, like or subscribe! it will surely make my day! creationsbynandini.wordpress.com

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 28, 2014

I read and liked a couple of your poems. Keep writing!

LikeLike

gingerjudgesyou

August 7, 2014

Love this: “I worry sometimes that we’re turning into a mass of quietly seething loners. We hold our words and thoughts inside, concerned about losing our jobs or offending our friends.”

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 10, 2014

Thanks, Ginger. I’m glad you liked it.

LikeLike