When we were young, my cousins and I got together at least once a week. We all grew up in big, Italian-Catholic families that were in a constant state of competition — the fathers vying to see who could smoke the most cigarettes, and the mothers to see who could have the most babies.

When we were young, my cousins and I got together at least once a week. We all grew up in big, Italian-Catholic families that were in a constant state of competition — the fathers vying to see who could smoke the most cigarettes, and the mothers to see who could have the most babies.

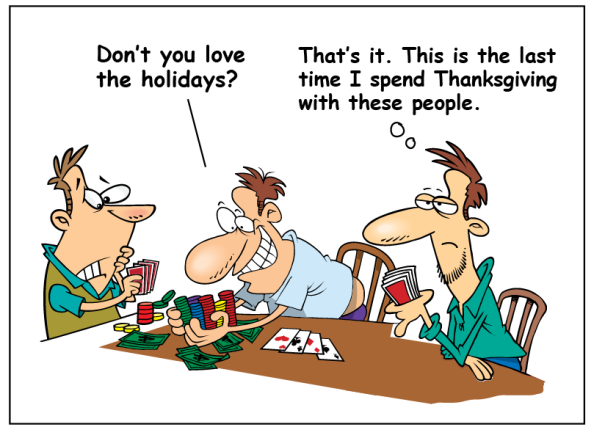

Holidays were enormous affairs, with cars parked on both sides of the street and coats piled high on my parents’ bed. While the men played gin rummy and drank from clear glasses cluttered with ice cubes, the women hovered around the stove, cooking food as though they were expecting the entire College of Cardinals to show up for dinner. Meanwhile, the children were sent outside to get some fresh air and sunshine, but mostly to stay out of the grown-ups’ hair. This was back in the days, of course, when the air was breathable and the sun was good for you, and when people could tell their kids to get lost without fear of lawsuits, leaked videos, or damaged self-esteem.

With few exceptions, the cousins were boys, and we spent a great deal of time ditching our sisters and figuring out new ways to make each other bleed. We would sword fight with broken broom handles, and climb fences that would have deterred death row inmates. When those didn’t do the trick, we’d use razor blades to cut our own thumbs, then press them together in a ritual that allowed us to declare ourselves blood brothers.

One of my cousins was an only child, so most of the time he had nobody to punch him in the face, or leave bite marks on his stomach, or snap the back of his thigh with a damp kitchen towel. As if unwittingly adhering to some minimum daily requirement for hemorrhaging, he was also the only one in the group who got nosebleeds. This would happen without warning, and for no apparent reason. We’d be wandering in a pack through an empty lot, or playing stickball in the street, when there would be a sudden commotion that would alter the sound and direction of our activity. I wouldn’t comprehend what was going on for several seconds, until someone blurted out, “He’s having another nosebleed!” Whatever we’d been doing stopped at once, rendered unimportant by the spectacle. We’d stare transfixed at our stricken kin, his head tilted back, fumbling with one hand to stem the flow, while cupping the other to catch it. And the sight would shock us, all over again, even though we’d seen it a dozen times before.

We could never understand exactly where the blood was coming from. The surface of the nose could bleed a little if scratched by a stray fingernail or an old can opener, or if you walked into a hedge. But even in our vast ignorance, we knew that liquids didn’t flow upward, and were sure it had to be draining down from inside his skull. This made it seem almost supernatural, and reminded me of the stories I’d heard about people who spontaneously developed stigmata — sores and wounds that corresponded to those of the crucified Christ. Bright red fluid pouring out as if from thin air, it was both a sacred and revolting event, one that we witnessed with fascination, but wouldn’t have wished on ourselves in a million years.

At the same time, as Catholics, the interjection of blood into our lives was familiar. Our homes were filled with religious icons: paintings, sculptures, and countless plastic trinkets, all depicting the suffering, death, and resurrection of Jesus. Many featured a floating heart, often crowned with thorns and dripping with blood. Sometimes the heart was outside his body, or could be seen through his robes, an unsettling image that tended to scare the life out of me.

At the same time, as Catholics, the interjection of blood into our lives was familiar. Our homes were filled with religious icons: paintings, sculptures, and countless plastic trinkets, all depicting the suffering, death, and resurrection of Jesus. Many featured a floating heart, often crowned with thorns and dripping with blood. Sometimes the heart was outside his body, or could be seen through his robes, an unsettling image that tended to scare the life out of me.

There were also statues that were alleged to bleed from their palms and feet, although these were scattered around the planet, and rarely in a convenient location. And every Sunday, we watched as the priest raised the chalice for all to see, proclaiming that the wine it contained had been changed into precious blood.

This was the source of my confusion. In church, blood was something holy, something to be held up and looked upon with reverence. Everywhere else, it was supposed to be kept hidden, and discussed in only the most mysterious terms. My mother often said that hers was boiling, or that someone had made it run cold. My father complained about some malicious individual who was out for blood, or people who acted as though they had royal blood. They both claimed blood was thicker than water, but that you couldn’t get any from a stone.

I had no idea what any of that meant. All I knew was that, competition or not, we were really part of just one big, Italian-Catholic family, and I hoped we would always be together.

We were, each of us, blood brothers. Even the girls, I guess.

* * * * *

Saturday, May 17th, is World Hypertension Day.

External bleeding is easily noticed. High blood pressure, though, is much less obvious. It increases the risk of stroke, as well as heart and kidney disease, and can cause weakened arteries and vision problems. Please check your blood pressure, and if it’s elevated, find out what you can do to lower it.

KL

May 17, 2014

Nice segue… I think 🙂 Your family gatherings sure do sound like fun though. Being an only child, married to an only child, and having only one, quite different different child, I sometimes lament that we don’t have those kinds of experiences. But then I remember that I don’t really like to share, and I realise that’s how it was all meant to be 😉

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 17, 2014

I always imagine that people with big families envy the smaller ones, and those with small families wish they had more relatives. As usual, though, the trick is to be happy with what we do have. It’s interesting that you’re an only child and so is your husband. Was that common experience part of the attraction?

LikeLiked by 1 person

KL

May 17, 2014

Good question. I don’t think so though. We met when we were just 18 and while he apparently fell in love at first sight, I took a little longer to fall in love and we were friends for a while first. Despite being only children we had very different family experiences and I don’t remember ever thinking of that as a connecting point for us. In a way it helps now though because I think it would be harder with our son if we had a big family. More people to explain things to I guess.

LikeLike

Rajiv

May 17, 2014

You draw an interesting comparison between hypertension and blood and family! The air, where you live, is much more breathable than where I live. The incidence of hypertension, where I live, is probably higher than the incidence of it in your neck of the woods.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 17, 2014

Rajiv, one of the statistics I read while working on this post said that 90% of adults over age 50 either already have — or will develop — high blood pressure. I wonder if they’ll eventually modify the charts to reflect where the norm is.

LikeLike

Rajiv

May 17, 2014

I doubt. When I was younger, I was told 120/80 is normal. Now, I am told 140/90 is normal. We, as a race, will kill ourselves

LikeLike

bladenomics

May 17, 2014

Outside of church, blood is still holy and quite useful in some parts of the world. To make blood statues and headlines -> http://www.odditycentral.com/pics/indian-sculptor-makes-creepy-bust-of-favorite-politician-from-his-own-blood.html

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 18, 2014

I’m afraid to even see what’s on the other side of that link. I may look later.

LikeLike

ranu802

May 17, 2014

I love reading your post,I learn so much from each one of your post. Yes today blood is heavy on your list.Although I’ve come to realize of late,blood relative doesn’t mean much these days, it’s only a way to get what they can out of you. Thanks for reminding us about hypertension which leads to all kinds of problems.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 18, 2014

I’m sorry to hear that’s been your experience with relatives, Ranu. But I’ve seen it, too. It can be very disappointing.

LikeLike

Marie

May 17, 2014

I fall so easily into the imagery of your stories that when they end I feel happily disoriented.

LikeLiked by 1 person

bronxboy55

May 18, 2014

I’d never thought of that as a useful goal, Marie — causing people to feel happily disoriented. Then again, maybe it is.

LikeLike

Anonymous

May 17, 2014

When I was back in NY for Spring Break, we went to visit one of those cousins. I sent my son outside to play in the leftover snow and sat on the living room couch. After about 5 minutes I told Theresa, “This is the longest I have ever been in your house!”. Then, I showed my family the secret closet where the stairs led to the attic bedrooms! Good times!

LikeLike

Chris Minch

May 17, 2014

I forgot my name

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 18, 2014

There was a secret staircase? Which house was this?

LikeLike

Chris Minch

May 18, 2014

The Monroe house. It led to Aunt Josephine’s room. I think Lisa lived up there, too. The stairs were in the closet.

LikeLike

Mikels Skele

May 17, 2014

A lovely memoir. I feel that your big family was a big clump of long-lost cousins of mine. Long after we all scattered and got distracted and distended by the Modern World, my mother kept stocking the fridge and cooking for the College of Cardinals, should even one of her errant children return for a visit. By the way, did you ever wonder why the Cardinals never graduated?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 18, 2014

They didn’t graduate — they just transferred to the Electoral College.

LikeLike

Andrew

May 17, 2014

I am one of those who has had hypertension all my life. It’s not difficult to treat, diet, exercise, medications all help.

and I find my BP strangely lowered after reading one of your posts…

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 19, 2014

Thanks, Andrew. Not true, I’m sure, but a nice thing to say.

LikeLike

shoreacres

May 23, 2014

I don’t know why it wouldn’t be true. There are certain places I never go when I’m online, because I can feel my blood pressure rising. So, it only makes sense that the reverse could happen.

LikeLike

Doug Bittinger

May 17, 2014

I am always amazed, Charles, by the amount of detail you recall from childhood. I remember very little of mine. I wonder whether that’s just old age and brain death or if some trauma has caused me to block it out. But I always enjoy hearing about your adventures. Thanks for another romp down memory lane, even if they are someone else’s memories.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 19, 2014

Doug, I’d be willing to bet that if you sat down and started writing about your childhood, you’d be surprised by the things you remember.

LikeLike

desertdweller29

May 17, 2014

I think we’re related… Big, Italian-Catholic family gatherings were holiday fare during my childhood. Only the older generation were Easterners (CT) and the newer generation were Westerners (AZ), which created Italian cowboys… I think we could have had a sitcom. Great post!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 19, 2014

Have you worked any of that into your novel?

LikeLike

desertdweller29

May 19, 2014

Yes, but in subtle ways. In hindsight, I should have worked in a cowboy yelling “forgetaboutit” instead of “giddy up”. 🙂

LikeLike

earthriderjudyberman

May 17, 2014

My godparents, when I converted to Catholicism, were Italian-Catholics and I enjoyed hanging out at their family gatherings. Like your family, they were a lot of fun and quite a contrast from my low-key, quiet Lutheran family. 😉

An ice-cold butter knife placed on the back of your neck will stop nosebleeds. I had more than a few as a child. I realize, of course, that your cousin would not have had the access to one while he was out and about.

I enjoyed your post. It brought back memories of my being a tomboy. That was another reason for some loss of blood. Loved your line “and climb fences that would have deterred death row inmates.” I’d jump from one tree to another next to it in our back yard. I’d congratulate myself for making it. Really stupid stuff. I’m surprised I survived childhood. 😉

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 19, 2014

I’m glad we both survived, Judy. And thanks for the butter knife tip. Even if it works, what ever made someone decide to try that?

LikeLike

Jac

May 17, 2014

Can’t believe you wrote a whole blog about blood and never mentioned the stains on the organ keys, that couldn’t even be removed when they used Bon Ami!

Now people will think we had a gruesome childhood… 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 20, 2014

Someone will know what that means.

And it was a squirrel’s skeleton…

LikeLike

thecontentedcrafter

May 17, 2014

I enjoy your memories! I wonder what the girl cousins were up to while you boys were finding more ways to make each other bleed ……….

LikeLike

Jac

May 17, 2014

I am his sister but am also one of the girl cousins. We were either jumping on the other girl’s bed and singing “Build me up buttercup” or swimming in the pool. Eventually, the boys would let us hang out with them or at least watch them play stickball or something 🙂

LikeLike

thecontentedcrafter

May 17, 2014

Thank you Jac, lovely to meet you in this cyber realm – weren’t they grand to let you watch them play their game! I always wanted to play with the boys – they had way more fun – all I was allowed to be was the Indian princess who sat and guarded the fire while they ran around shooting at each other – or the score keeper or ‘spare on the bench’ – depending on the game 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 21, 2014

I guess while you were doing all that sitting and watching, you were also developing your creativity.

LikeLike

silkpurseproductions

May 17, 2014

The large family gatherings are definitely to be cherished. Our have become pretty much non-existent and they are missed. You Catholics really are hard core if you already knew what “stigmata” is at such a young age. I don’t believe I even heard the term until I was in my 20s.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 21, 2014

I hadn’t heard the actual term stigmata either, Michelle. But we heard plenty of stories about them from the nuns.

LikeLike

D Holcomb

May 17, 2014

You are such a gifted writer, Charles. Loved this story. Although the whole blood-thing makes me anxious. Still, you cushion it in the safety of fond memories.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 21, 2014

Thank you again for the kind words, Diane. I always appreciate your encouragement.

LikeLike

Chichina

May 17, 2014

I once had a client who felt the need to talk about her hemophiliac nephew’s inter-cranial bleeds. If it was early in the morning I’d have to excuse myself and go into the library where I would put my head between my knees until the nausea and dizziness passed.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 23, 2014

I’d have had the same reaction. I think there’s something disturbing about the word bleed as a noun.

LikeLike

Chichina

May 23, 2014

It’s downrignt lethal when combined with the word “inter-cranial”. Oh god…..

LikeLike

reneejohnsonwrites

May 17, 2014

This supports my theory that kids and dogs should always be given a firm task. If not, they’ll create one and chances are, things like blood-letting will ensue, or in the case of said dog, you’ll return to find your chaise lounge cushion shredded and the lawn full of foam. Just saying. Don’t you wonder how we managed to survive with all of the crazy stunts we pulled? Some of ours involved snakes. Don’t ask.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 23, 2014

I don’t remember ever receiving specific instructions, beyond “Get out of the house.” It is amazing that we survived — and our stunts never involved snakes. I won’t ask.

LikeLike

daisy

May 18, 2014

I don’t know if your cousins read your blog, but they should. Then this line would be true: “…and I hoped we would always be together.” My family had similar get-togethers, poker and cigarettes in the basement, coats piled high on the beds. So visual, your writing takes me right through the memory.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 23, 2014

I wonder if your family has managed to stay together, Melissa. Ours hasn’t. We’re scattered all over North America.

LikeLike

melissa

May 23, 2014

Charles, we’ve scattered as well. I guess what I meant was that your writing brings people straight into their memories, and in that way, brings them together. It’s beautiful.

LikeLike

icedteawithlemon

May 18, 2014

As the mother of three boys, I had to laugh at “figuring out new ways to make each other bleed.” Oh, so true, and yet they all survived and seem to love each other dearly despite the bloodshed–funny how that works. My boys (and I) grew up in a time and place where we, too, were sent outside for hours on end with no worries of “lawsuits, leaked videos, or damaged self-esteem,” but back then neither I nor my parents (or yours) had to worry about predators driving by attempting to snatch our children away from us, either. It’s a shame that most of today’s children and parents will never know such exhilarating freedom.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 23, 2014

Karen, you’re right that parents back then had less to worry about. I don’t remember ever hearing concern about kids being snatched or harmed by strangers. The fear was mostly that one of us would walk out into traffic and get hit by a car — which also never happened.

LikeLike

Choosing

May 18, 2014

We just had quite a big family gathering at our house. No nose-bleeds though, just a bleeding toe – no idea how little one managed to hurt his toe, but after we covered it with a plaster he was ok again (funny how covering things up makes them go away, at least in children’s minds). I think what suffered most were the plants in the garden… getting hit by the inevitable balls a lot.

I used to have nose-bleeds a lot as a child.. I remember I even once had one at an exam at school – we had to write something about religious education, and I think I made a blood stain on the paper… Not sure if that improved or lowered my grade though.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 23, 2014

A blood stain on a religious exam — that had to help.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Alyaap2

May 18, 2014

Reblogged this on Alya Mawalika Khavianiston.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 23, 2014

Thank you. I’m glad you liked it.

LikeLike

Philster999

May 19, 2014

I thought every day was Hypertension Day? (Or maybe that’s just me…)

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 23, 2014

I’m afraid you’re right, Phil — every day is Hypertension Day. And I suspect it’s getting worse all the time.

LikeLike

cat

May 19, 2014

Nose bleeds are “fun” … especially during a job interview or when he proposes marriage … and you are about to say “Yes” … good timing … just great … and very memorable … I can attest to that … smiles

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 23, 2014

There’s probably some culture somewhere that believes nosebleeds are good luck, even during a marriage proposal. (Did that really happen to you?)

LikeLike

Nel

May 20, 2014

This brought me back to my childhood. I also grew up in a Catholic household and my mom made me participate in this yearly tradition called Flores de Mayo along with my cousins (mostly females). We’d dress up as angels and offer flowers for Mother Mary at the altar; every afternoon for the whole month of May (which is summer break in the Philippines). It was fun mostly because after that we’d get free cookies and juice; and play with the other angels.

Things are a bit different now, though. I don’t enjoy family gatherings as much and I don’t think I’ll ask my kids (if I have any) to spend their afternoons dressed up as angels.

Do you still have great, big family affairs, Charles? Seems to me Italians and Filipinos have a lot of common traditions.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 23, 2014

You’re probably right about the common traditions, Nel. I’m afraid many of those traditions are disappearing, though, and quickly. At least they have for our family. I hope you manage to hold onto a few — at least the ones you liked.

LikeLike

accidentallyreflective

May 21, 2014

Your childhood sounds like a lot of fun! I am the only child you speak of- that would join my cousins and their large families and enjoy adventures with them only to ruin them by having an asthma attack or an allergic reaction 😦 Really intrigued to see you were raised a Catholic and no longer believe in God. Do you still have family gatherings like you used to? We don’t and that does sadden me because we have such great memories together. Thank you for such a great post yet again . I think I may write about some childhood memories – you inspired me!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 23, 2014

I’m glad you’re feeling inspired. You could write about some of those childhood memories and then invite family members to read your blog. Maybe another gathering will result. It’s worth a try.

LikeLike

accidentallyreflective

May 28, 2014

Yes I think I will! Thank you! Although recently I am finding it increasingly difficult to find time to sit down and write. Its the summer months and we seem to be out more- can’t win!

LikeLike

Patti Kuche

May 21, 2014

My mother was always going on about her blood pressure being up so high we kept waiting for blood to burst from the top of her head.

Don’t forget Charles, Jesus was also an only child!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 23, 2014

Did your mother know about Saint Andrew Avellino, the patron saint of high blood pressure? (It’s true — I just looked it up.)

http://www.holygifts.com/Healing-Saints-Relic-Cards-Saint-Andrew-Avellino-Patron-Saint-of-Strokes-and-High-Blood-Pressure-Pack-of-12.html

LikeLike

shoreacres

May 23, 2014

Of all the details here, the one that caught me was the pile of coats on the bed. They were a part of all family gatherings, as well as my folks’ parties. In fact, most of what I remember of my parents’ parties during my childhood and early youth is piles of coats. I always got sent to a neighbor’s house so I could “sleep better”. Read: “So I couldn’t witness what was going on.”

Of course, there wasn’t a lot of blood spilled during my childhood, so it really didn’t affect me much, one way or the other. Well, until I got to MacBeth. “Out, out, damned spot” was one of my mother’s favorite lines — who knows why? And I still remember MacBeth’s soliloquy when he describes how Duncan will be murdered. “I see thee still, and on thy blade and dudgeon gouts of blood, which was not so before.”

That Shakespeare dude could write.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 26, 2014

I wonder if the stage productions during Shakespeare’s time even bothered with the fake blood. If they did, it would have been a lucrative business for whoever was manufacturing the stuff. You could have built a career on Macbeth alone.

LikeLike

Mal

May 24, 2014

Haha, Charles, believe it or not but my this month’s post is on blood, knives and severed limbs…about a movie my friend and I went to see. It was gruesome, ne’er to watch again. But your childhood sounds fun and daring like a swashbuckler’s life – thank you for sharing the precious memories. 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 26, 2014

Just finished reading your post, Mal. It’s a wonderful description of the film (whatever it’s called), and your reactions to it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mal

May 26, 2014

Thank you so much, Charles! Very kind of you. God bless.

LikeLike

Speculating Sunrise

May 25, 2014

I come from an enormous, very loud and quite religious family as well. I absolutely loved your detailed descriptions, they reminded me of certain spectacles that I witnessed during family gatherings and holidays when I was a kid (the competitiveness amongst the ‘macho men’ of the family for example). In different variations, of course. Enjoyable read. 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 26, 2014

I still remember the first time I went to a cousin’s house as an adult. After dinner, I got up to help clear the table and wash the dishes, while the other males all sat there like princes. It was quite an uncomfortable situation.

LikeLike

John

May 27, 2014

Man, I think every grade school class had that one poor child whose nose bled regularly. Often, it was the result of a punch in the face. Or so I hear.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 28, 2014

Maybe we were seeing the result, but missed the cause.

LikeLike

Sandra Parsons

June 12, 2014

I always hated the expression “blood is thicker than water”. My sister and I have never been very close, we are just too different. On the other hand I have friends I would do anything for (and they for me), so what shall I make of this stupid saying? After all, you can’t choose your relatives. Not to mention that my friends have blood in their veins, too.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 13, 2014

My mother used that expression a lot, too, and I never really understood what it meant. What did water refer to?

LikeLike

Sandra Parsons

June 13, 2014

Yeah, what? Are we all drinking water? Swimming in it? Who knows?!

LikeLike

kasturika

June 13, 2014

We sometimes speak about being blood-related… I was just wondering… did the sight of blood never make anyone nauseous? Bloody hell! I’m getting queasy…

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 13, 2014

Yes. Usually the girls.

LikeLike

kasturika

June 13, 2014

😀 I should have guessed!

LikeLike

Glenn Manderson

June 13, 2014

I was once in charge of Blood Donor recruitment and we held a clinic where we only invited people by the name of Stone, finally proving that you could get blood from a stone!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 14, 2014

Is that a true story? It sounds like a great marketing idea.

LikeLike

Daddy Bear

July 5, 2014

“…find out what you can do to lower it.” I have two sure, never fail cures: (1) pet my service dog, and (2) read something funny.

Thanks for helping me with my blood pressure…

😀

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 7, 2014

Have you tried reading something funny while petting the dog?

LikeLike

Daddy Bear

July 7, 2014

Yes, but I tend to giggle out loud, and the dog looks at me funny, which makes me giggle more, and then the dog leaves the room, embarrassed that he knows me…

LikeLike