If I sit perfectly still and squint a little, I can venture back in time, through the dusty drapes of my memory to the early days of childhood. As the years contract and slide behind me, I feel myself shrinking, my arms and legs growing thinner, my mind releasing its vast collection of clutter.

If I sit perfectly still and squint a little, I can venture back in time, through the dusty drapes of my memory to the early days of childhood. As the years contract and slide behind me, I feel myself shrinking, my arms and legs growing thinner, my mind releasing its vast collection of clutter.

After the final barrier yields and drops away, I break out into an open area where the whole world is down here, flat and cool, and where the ceiling might as well be the sky. It’s clear and quiet. My short pants are corduroy, held up by suspenders. I am three years old. A smooth, white, metallic box rests on the linoleum floor. I kneel in front of it and begin to turn the thin crank on its right side. The song Pop Goes the Weasel matches the speed of the crank, sounding stifled and clunky, as if I’m listening to it from the next room, with my ear pressed to the wall. After fifteen seconds of tentative turning, the lid on the box releases and a demonic toy clown flies from its depths, swaying and squeaking and scaring the life out of me.

As much as I hate this experience, I can’t stop. Once my heart resumes a normal pace, I push down on the top of the clown’s head, close the lid, and repeat the ritual. Again, and again.

Most likely, my mother has sent me away from her private conversation and told me to go play with the jack-in-the-box. But that’s never how it feels. It seems more like the clown is the one who’s playing, and is letting me participate only because it needs air, but can’t reach the crank from inside its container. Adding to my anxiety is the fact that his emergence never becomes predictable. Rather, he leaps up at different points in the song, as if to prevent me from adjusting to a pattern and preparing for the fright. I don’t like the clown’s face, especially his smile and the texture of the plastic, and am compelled to seal him under the lid. But once hidden, he sends an irresistible signal to my brain, and I again set him free.

Most likely, my mother has sent me away from her private conversation and told me to go play with the jack-in-the-box. But that’s never how it feels. It seems more like the clown is the one who’s playing, and is letting me participate only because it needs air, but can’t reach the crank from inside its container. Adding to my anxiety is the fact that his emergence never becomes predictable. Rather, he leaps up at different points in the song, as if to prevent me from adjusting to a pattern and preparing for the fright. I don’t like the clown’s face, especially his smile and the texture of the plastic, and am compelled to seal him under the lid. But once hidden, he sends an irresistible signal to my brain, and I again set him free.

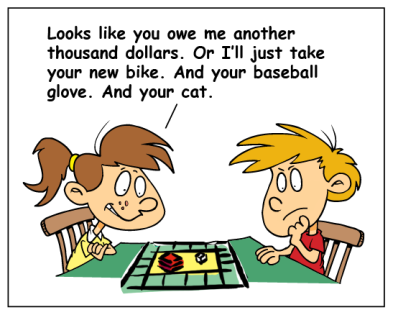

The jack-in-the-box is my introduction to pointless diversions that appear to be designed for nothing more than pure annoyance and frustration. A few years later, I am playing board games that require the roll of dice, or the careful flick of a spinning arrow. In the most memorable example, the goal is to disperse four colored tokens from the safety of my home area, launching them out into traffic around a long, senseless loop and back again. After my turn, one of the other players inevitably lands on the same space. My piece is kicked out and I have to start over. I don’t understand. The space has plenty of room for both tokens. Besides, I was there first, so why am I the one who has to leave? Just as the jack-in-the-box was supposed to help develop valuable hand-eye coordination, this one has been marketed, I’m sure, as a way to learn strategy, patience, and perseverance. The only thing I’m learning, though, is that my brothers and cousins are out to get me, and that they’re all stupid jerks. Whenever they show up, someone pulls out the game, or some variation, and I’m once more subjected to the humiliation of being returned, repeatedly, to the very spot where I began.

This game will soon be replaced by more complicated alternatives, each riddled with mysterious rules that I try but fail to comprehend. Out of all the games I despise, my favorite is one called Life. It allows me to move a small car around a board that includes bridges, banked hills, and a built-in spinner. I’m so distracted by these novelties that I sometimes fail to notice how pathetic I am at actually playing the game. I never win, but I don’t care. At least I’m not being sent back to the beginning every time I start to make some progress. Most intriguing is this idea that I get to decide things for my family. And I get to drive. The car has six holes, meant to accommodate plastic pegs that represent me, my wife, and our children. The rule book for Life is also where I first come across the word spouse. Much later, in my real life, I will be momentarily startled when I meet a man who has a spouse, and her name is Peg.

* * * * *

The worst game of all is Monopoly. Right from the beginning, I am thrown off balance by the choice of tokens, forced to decide if I want to be a dog, an iron, a boot, a thimble, a purse, or a hat. No matter which I choose, someone makes fun of me.

“You want to be an iron?”

No. I don’t want to be any of them, but they all picked theirs before I had a chance, and the iron is the only one left. I really just want to watch cartoons. But as with the jack-in-the-box, I’ve been somehow coerced into participating in this grueling ordeal. I march around the board, taking two hundred dollars from the banker and almost immediately forking it over to someone else because I’ve landed on a property where he’s built a string of hotels. Who told him to put all those hotels there? Not me. I’m just passing through, not spending the night. I don’t even know where I’m going. There’s no end in sight, and when I look ahead, I see only an endless path of financial obligation.

The cash continues to vanish. I land on Water Works, which is just a picture of a faucet that, for some unknown reason, turns into another debt. I draw a card and am told to pay a luxury tax on a diamond ring. I don’t remember buying a diamond ring. I’m an iron. What would I even do with a ring? I’m sent to jail without explanation or legal representation. I land on a railroad and I’m out a huge wad of cash. Then I owe money to a guy named Marvin Gardens. Suddenly, I don’t have a white dollar bill to my name, and I’m confronted with yet another new word: bankrupt.

* * * * *

When the adults invite me to join their games, the story is pretty much the same. We play Crazy Eights, an activity with rules so complex that I’m sure the other players are inventing them as we go along. We play bingo, but I can’t keep up, and while I’m searching for B-12 or G-47, the caller is already three numbers ahead. We play gin rummy, and I show my hand to my father, who shakes his head and advises me to pick another card.

As my aunt scoops up her latest pile of winning chips, I think of the jack-in-the-box, and how harmless and lovable he really was. I wonder where he is now, and if there’s a small, nervous child around who occasionally pops open the lid for him. I miss that little clown, and his kind face. I hope he’s still smiling.

Chichina

March 24, 2014

I love your sojourns to your past, amigo. As adults, we can often forget how perplexing life can be to children.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 25, 2014

When exactly does that perplexing thing stop?

LikeLike

Patti Kuche

March 24, 2014

That advertising slogan “fun for the whole family!” didn’t fit with us. So pleased to see I am in good company, thank you Charles, you dealt a good one here!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 25, 2014

Didn’t the games always come in a box with pictures of people having the time of their lives? That wasn’t us either.

LikeLike

georgettesullins

March 24, 2014

I like games with a beginning, middle and reasonable end. Monopoly went on forever like “This is the song that never ends”. I just never liked singing that tune. Give me word games like good ole “Password” now replaced by “Outburst” or “Taboo.” And, I love to play Scrabble even if I lose. If I come up with a great 5, 6 or 7 letter word, I really don’t care if I win.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 25, 2014

I’m the same way, Georgette, especially with Scrabble. I tend to go for the elegant move, rather than the high score. Monopoly was a little too complicated, or we were just too young. I’m surprised we didn’t beat each other up after every game.

LikeLike

ranu802

March 24, 2014

It is hard being a kid the good old adults always make fun of you.Monopoly is quite the game,my brother always stole money from the bank,he conveniently sat next to it and stole the play money whenever he was out of cash. You could do the same but I forgot you were the kid, you felt safer with Jack-in the Box, than Scrabble or Monopoly. You probably like them now,you’ve learned the trick.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 26, 2014

I often suspected one of my cousins of stealing, too, Ranu. Somehow, he was always the banker.

LikeLike

Mikels Skele

March 24, 2014

Monopoly. Two older brothers. Enough said.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 26, 2014

A game isn’t much fun when the only thing you have to look forward to is Free Parking. Good to hear from you, Mikels.

LikeLike

Mikels Skele

March 26, 2014

Or when new rules emerge every time you think you’re getting ahead. 😉

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 27, 2014

I find that always happens when I’m learning a new game with someone who’s played it a lot. It’s the “Oh, I forgot to tell you” rule.

LikeLike

The Moon is a Naked Banana

March 24, 2014

Children are no better than adults in their addiction to doing things which fill them with fear. You do not like it, you would be angry if anyone else did it to you, but it is something that you have to do.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 26, 2014

Something like those rides at the amusement park.

LikeLike

icedteawithlemon

March 24, 2014

I so love when you pull back the “dusty drapes” of your memory to re-visit your childhood days. Not only do you express those memories with such eloquence and charm, but every time–every time!–your stories elicit long-buried memories of my own. I was always bored by Monopoly and often took wild risks to speed up bankruptcy so that I could go ride my bike or read my book. But when my mom finally introduced me to card games–Old Maid and then rummy and then Rook–ahh, those were special days indeed. Thanks for the memories, Charles.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 26, 2014

Thank you, Karen. I’d forgotten about that tactic, learned after too many endless games, of losing on purpose. I used to get into arguments with opponents who wanted to lend me money so I could keep playing. I have a feeling some of them grew up to become real bankers.

LikeLike

Kathryn McCullough

March 24, 2014

Gosh, I love that line–“The ceiling might as well be the sky.” Fabulous, especially to someone who is writing a memoir about my childhood. Hope you have a merry Monday, my friend.

Hugs from Ecuador,

Kathy

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 26, 2014

Thanks, Kathy. I hope the memoir is going well.

LikeLike

susielindau

March 24, 2014

Our generation played a lot of board games for the lack of better things to do. Somewhere along the line, I burned out on them. Every once in a while, I get the urge to play Scrabble…. 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 26, 2014

But do you still have a collection of board games, stacked up on a shelf in the back of a closet?

LikeLike

susielindau

March 26, 2014

We have almost all of them. Danny used to be in the wholesale toy and school supply business. 🙂

LikeLike

genusrosa

March 24, 2014

I was fascinated with Author Cards…could have played it for hours if my older siblings had indulged me; now I collect the actual books instead of the cards. Loved the ‘spouse named Peg’…once again you’ve given us a great journey back in time!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 26, 2014

Games that are both fun and educational — there’s an idea that still hasn’t quite caught on.

LikeLike

Diane Henders

March 24, 2014

Thanks for the chuckles, as usual! I’ve never played Life, but your take on Monopoly sounds a lot like life to me: “I don’t even know where I’m going. There’s no end in sight, and when I look ahead, I see only an endless path of financial obligation.” I don’t even have a ‘Get Out Of Jail Free’ card… 😉

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 26, 2014

I have doubles, Diane. I’ll send you one.

LikeLike

Diane Henders

March 26, 2014

Awesome! Thanks! 🙂

LikeLike

sheenmeem

March 24, 2014

Loved the post. Brought back all the nostalgia of childhood.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 27, 2014

I’m glad you liked it.

LikeLike

Marie

March 24, 2014

In this sharing your lyricism as a storyteller outshines the humor that I have come to identify as a hallmark of your craft. Love!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 27, 2014

Thanks, Marie. I consider you a master of lyricism, so your positive feedback means a lot.

LikeLike

Diane Holcomb

March 24, 2014

God, that Jack-in-the-Box was scary. You’re right! There’s a giant automated plastic character named “Laffing Sal” at a funhouse in San Francisco that scares the bejesus out of me, even as an adult. She looms over you, bobbing and wobbling and cackling. It’s downright creepy.

Thanks for the memories, pal. I think I need a tranquilizer.

Love your writing, and humor. Look forward to your next post!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 27, 2014

It’s interesting that the very word — funhouse — makes us a little uneasy. I wonder why we equate fear with fun.

LikeLike

earthriderjudyberman

March 24, 2014

I wonder if that jack-in-the-box is the reason that some kids are afraid of clowns. That would unhinge me. Your experiences, Charles, mirror many of mine. Your stories are funny. Great therapy as I try to avoid the painful memories of childhood and board games.

Bless my Grammy for teaching me how to play Solitaire and how to cheat it. She told me she was playing the Devil and had to cheat or he’d win. Seemed logical to me. 😉

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 27, 2014

I think you’re right, Judy. And real clowns are so much bigger, and tend to do weird things. It seems to have something to do with unpredictability.

LikeLike

thecontentedcrafter

March 24, 2014

I almost spat my morning coffee when you revealed your momentary discombobulation on meeting a man with a spouse named Peg …….. fantastic sentence! Fantastic post – I am waiting – and shall buy the book 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 27, 2014

Which book?

LikeLike

thecontentedcrafter

March 27, 2014

The one you are about to write based on your blog posts 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 28, 2014

I did publish one at the end of 2011, so it includes only the first year and a half. (See the My Books page above.)

LikeLike

reneejohnsonwrites

March 24, 2014

I adore board games. As kids, we didn’t hang around a television set. We played board games; monopoly, battleship, scrabble, operation. A real slice of nostalgia here.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 27, 2014

I still like Scrabble, too. And there’s another one called Upwords. Have you played that?

LikeLike

Greg

March 24, 2014

Monopoly; causing family arguments since 1933!

Never played with a Jack in the Box, but I hate clowns, so I can’t imagine that would have gone too well, either.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 27, 2014

It’s amazing how many people hate clowns. How did they ever get to be so popular, and prevalent?

LikeLike

Aarti

March 25, 2014

I remember playing Ludo with my cousins and losing every time because they used to move the tokens when I wasn’t looking! You and I seem to have had the same experience with Monopoly too!

I enjoyed this post a lot! 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 28, 2014

Maybe if I’d tried a little harder at Monopoly, I might have learned a little more about money, and how to handle it. I’ve never heard of Ludo. Is it the same kind of game?

LikeLike

Aarti

March 31, 2014

The game involving moving four coloured tokens from your home area through a loop which you’ve mentioned in your post is called Ludo! 🙂

LikeLike

She's a Maineiac

March 25, 2014

Don’t feel bad. I was always the boot in Monopoly. So humiliating. And no matter what I rolled with the dice, I ended up in jail or “just visiting” jail. I don’t think I ever won that game once as my brothers were ruthless. They’d buy out all the hotels and somehow manage to put all of them on the spot I would land on over and over again.

My kids love to play UNO, now there’s a game for me. I actually can understand how it works. I still lose, though.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 28, 2014

At least the boot could walk. Or hop. Wasn’t there also a thimble? They seem to have put a lot of thought into the rest of that game. Who was running the token department?

I don’t like Uno, because it requires you to say the name of the game. You could completely wipe out your opponents, but if you don’t yell “Uno!” you don’t win. That bothers me, although I don’t really know why.

LikeLike

morristownmemos by Ronnie Hammer

March 25, 2014

My husband and his sibs used to cheat when they played Monopoly. They’d hide money and act poor: just as in real life. I never thought that playing with them was any great fun, but I was older then. My childhood consisted of family board games that were much simpler, like Parchesi and checkers. But we were fun, not cut throats.

That must be why we never became rich!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 28, 2014

I always felt sorry for the other players, Ronnie, and I bet you did, too. That’s probably the real reason we never won.

LikeLike

Talk to me...I'm your Mother

March 25, 2014

This SO MUCH reminds me of playing cards with the older girls. They would tell me to hold up my hand. I would raise my hand and they would collapse into giggles (after, I’m sure, taking one more peek at my hand). Days of trying to keep up….

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 28, 2014

And we wonder where all of these computer hackers came from. They were the same people who used to cheat at Monopoly and cards when they were kids.

LikeLike

Talk to me...I'm your Mother

March 28, 2014

Or their children!

LikeLike

raeme67

March 25, 2014

I usually win at card games., Except that time when my brother cheated at UNO, He was hiding draw four wild cards up the sleeves of his shirt, pretending to drop a pencil, ducking under the table to retrieve the pencil and to remove a draw four wild card from his sleeve. All went well until the 3rd or 4th hand when one concealed card fell out of his sleeve unplanned. The game ended with a very mad older sister dramatically stomping off and slamming her bedroom door, muttering curse words under her breath.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 28, 2014

The fake pencil-drop was one of the essential strategies of childhood.

LikeLike

raeme67

March 28, 2014

Obviously, it worked out for my brother,until the unfortunate day. 🙂

LikeLike

Elyse

March 25, 2014

You had me in tears with “I don’t remember buying a diamond ring. I’m an iron!” Brilliant. I always insisted on being the doggie or I wouldn’t play. I still hate ironing!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 29, 2014

There was a cool car, but someone else always picked it first. And there was also a ship, although it tended to tip over a lot, which didn’t help my confidence.

LikeLike

Doug Bittinger

March 25, 2014

Brilliant. I haven’t played games in a couple of decades, and for good reasons. Most of these you just listed. Games are supposed to be fun, right?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 29, 2014

The people pictured on the box seem to be having fun. But then, so do the people shown on tax software packaging.

LikeLike

Stacie Chadwick

March 26, 2014

Charles,

For me, there’s no comparison between anything involving a clown (or worse, a mime) and board games. Clowns are evil creatures that should be eradicated from this earth and just capture all the railroads in Monopoly and you’ll be fine. 😁

Stacie

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 29, 2014

So what is it about clowns and mimes? Is it the silence? Or their penchant for gloves and an abundance of makeup? Whoever handles their public relations has been doing a lousy job.

LikeLike

Stacie Chadwick

March 30, 2014

All of the above plus their reputation for being loud chewers.

LikeLike

jeanjames

March 26, 2014

Great story!! Now that I have children of my own, I’m back to playing all of my childhood games, and am reminded of how much I didn’t like them then or now. As for those Life game pegs, someone dared me to eat one once during a game and I did, I guess it was a Life game of truth or dare, much more exciting than just a plain old board game. (I completely forgot about that until reading your post lol). Now you’re shaking up my ‘dusty drapes’.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 29, 2014

Maybe you can answer a question for me, Jean. Was the name of the game Chutes and Ladders changed back to Snakes and Ladders? That has to be the worst title for a kids’ game I’ve ever heard.

LikeLike

jeanjames

March 29, 2014

I took a kid survey (because I just happen to have a housefull of kids for a birthday party) and none of them heard of Snakes and Ladders. So these modern day kids said, “Google it”, which I did and found out that Snakes and Ladders was actually an ancient Indian game that made its way from India to England then to the States where the name was changed to Chutes and Ladders. The Chutes resemble the shape of the snakes. The ladders symbolized virtue and the snakes symbolized vices. Who knew such a simplistic childhood game had a lesson in morals and values. I couldn’t find any information that they were changing the name back though. Thanks for the question, I learned something new today…lol.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 30, 2014

I saw the game in a store recently, and it was called Snakes and Ladders. I understand that was the original name, but it just sounds too scary for little kids.

LikeLike

jeanjames

March 30, 2014

I agree it does sound scary for little kids. What store did you see the game in?

LikeLike

Betty Londergan

March 26, 2014

I just spent the afternoon with an 11-month old girl, and we were doing fine until I played the Jack-in-the-Box (and it was an old, wooden version – not even the super scary modern kind) — and she looked at me in shock and burst into tears. So .. yeah, I feel you! And p.s. I always felt totally stupid and overwhelmed by all the card games and — Concentration. Even the name still gives me an insecurity attack!)

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 29, 2014

I think the jack-in-the-box is parental revenge for all those sleepless nights caused by their newborn children. And the fact that there’s an old, wooden version just means that the problem has been around forever. As for the card games, I still feel stupid, especially because I always seem to be the one trying to learn the rules — from people who have been playing the games for years.

LikeLike

Sandra Parsons

March 26, 2014

Reading the comments, I feel less bad. Is there anyone out there who actually likes (or wins at) Monopoly? It just makes sense that my stint as a banker was a rather brief one.

I like games where strategy outweighs chance, but even those tend to screw me over sometimes due to my damn bad luck in rolling dice. And then there are the ones where you end up as “collateral damage” to your spouse’s strategy. Worst marital argument ever! On the whole, I think I’m better off hitting the movies. Thanks for the giggle though.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 29, 2014

If we can just continue to avoid getting trapped into learning bridge, I think we’ll be all right. (You don’t play bridge, do you?)

LikeLike

Sandra Parsons

March 30, 2014

I’ve resisted every attempt the English side of my family made to teach me. Well, I think my brain deserves the credit for this achievement, not my willpower 😉 We Germans play Skat and Doppelkopf instead.

LikeLike

silkpurseproductions

March 27, 2014

We weren’t allowed to play games that had cards as my grandmother insisted they were “the devil’s tools”. There was one exception, though. It was a game called “Lexicon” and it was exactly like scrabble except the letter tiles were cards. I learned a lot from that game and enjoyed it. We also played crokinole which was a big wooden disk with a drop out in the centre. You would flick little round disks and try to get them as close to the centre as possible while knocking your opponents off the board, with the big payoff being getting it right in the hole. Those other games were played at friends houses. We didn’t have them.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 30, 2014

I’d never heard of crokinole until a few years ago, Michelle, but apparently it’s very popular here in Atlantic Canada.

LikeLike

silkpurseproductions

March 30, 2014

It was a family/friend favourite in our house. We use to have “tournaments”. The best part was that all ages could play. Some of the grandchildren’s favourite memories are playing crokinole with their grandfather.

LikeLike

Chris12

March 27, 2014

Nice post Charles. For me, it has to be the game, Sorry. It gave me the satisfaction of sending my brother back to his home base. Plus, it allowed sarcastic apologies. What’s better than a sarcastic apology when you’re a kid?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 30, 2014

Parcheesi, Sorry, Trouble, Aggravation — aren’t they all the same game?

LikeLike

Philster999

March 29, 2014

OK, I laughed so hard at your Life / wife-named-Peg epiphany that I think I peed a little…

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 30, 2014

True story, Phil. And probably the only epiphany I’ve ever had

LikeLike

daisy

March 29, 2014

Charles, this was beautiful. What a literary journey you took us on in those opening paragraphs. Just lovely.

And I’m sorry you always had to be the iron. I used to grab for the Toto dog so quickly I always got him. But now I have a daughter and her 5-year-old reflexes beat me every time. 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 30, 2014

Have you seen all the variations of Monopoly? I think every city in the world has its own version.

LikeLike

Choosing

March 30, 2014

I never had the nerve for Monopoly…. it just took soooooo (yawn!) loooooong!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 2, 2014

I wonder what the world record is for longest Monopoly game.

LikeLike

Barbara Rodgers

April 1, 2014

Ah, the games people play… Thanks for the chuckles this morning! You make me remember how baffling it can be for a child trying to understand the world of older folks. We play a lot of “The Settlers of Catan” with our kids and their spouses these days.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 2, 2014

There’s another game I’d never heard of, Barbara. Is it something like The Oregon Trail?

LikeLike

Barbara Rodgers

April 7, 2014

I had never heard of the Oregon Trail game before, but my husband informs me that it’s an online game. Settlers of Catan is a very complicated (to me) strategy board game… I never win but do enjoy the attempt.

“Players assume the roles of settlers, each attempting to build and develop holdings while trading and acquiring resources. Players are rewarded points as their settlements grow; the first to reach a set number of points is the winner.”

LikeLike

rangewriter

April 6, 2014

I never cared for games either, especially card games cuz those didn’t even have any cool bridges, dials, cars, pegs, or other accoutrements. I’m mystified by how many people have graduated from boring card and board games to time-sucking online games. Take your farm and get outta my way! ;-}

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 13, 2014

Games of some kind have been around for thousands of years. I wonder what psychologists have to say about them.

LikeLike

rangewriter

April 15, 2014

Probably something about keeping the mind active and bonding with other humans. I’d rather read a book.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 7, 2014

Me too.

LikeLike

lostnchina

May 19, 2014

During my time in China, I’d taken to playing online Scrabble with people around the world and have only very recently realized how sad an activity this is. While I enjoy the challenge of learning new words and strategies, I’ve no desire to know that I’m playing against Becky from Montana, whose dog has some goiter, or Bob, who wants to know how far China is from Pocatello, Idaho, and whether I’m married. A lady actually swore at me the other day (ie. Typed a bunch of curse words on the computer in the little chat box on the right side of the screen), because I wouldn’t extend her time. (She was trying to spell something like, CAKE, and it took her more than 2 minutes.) We non-socializing board-game players who like board games are all doomed, Charles. Hilarious post, and oh so true.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

May 23, 2014

Your online Scrabble adventures would make a great post, Susan. Or have you already published one? If you have, please let me know, because I’d love to read it. And how did you finally get rid of Bob from Pocatello?

LikeLike

lostnchina

June 13, 2014

That’s a great idea for a post, Charles. As for Bob from Pocatello, you’ll just have to read it in the yet-to-be-written post, I suppose.

LikeLike