As kids growing up in the North Bronx, we spent our summers mostly roaming the streets and alleyways, picking through the rubble of empty lots and analyzing anything that seemed out of the ordinary.

As kids growing up in the North Bronx, we spent our summers mostly roaming the streets and alleyways, picking through the rubble of empty lots and analyzing anything that seemed out of the ordinary.

One of my friends found a five-dollar bill once, which in those days was a small fortune, enough to buy a car dealership, or keep you in Bazooka Bubble Gum for the rest of your life. It happened while we were searching for abandoned deposit bottles. We’d been hoping to accumulate enough pennies to purchase a bag of potato chips or a box of Milk Duds that we could share. If we were feeling especially foolish, we might even combine our cash to buy a pack of baseball cards, a risky endeavor that too often produced the same results you’d expect when a group of adults gets together to invest in lottery tickets.

And then, there it was, folded in half and standing vertically in the tall grass. For a good ten or fifteen seconds, the thing wasn’t real. It was some scrap of paper, maybe a picture torn from a magazine. Something that only looked like a five-dollar bill. After all, anyone who lost that much money would be out there with a sickle in one hand and a shotgun in the other. But, no, it was legal and tender and genuinely authentic, and it vanished into the boy’s shirt as rapidly as it had appeared. So did he, as I recall, wisely scampering home before the rest of us had time to close our mouths.

“Finders keepers, losers weepers,” my father said later. I tried without success to comprehend either the ethics or the grammar of his statement. He elaborated: “Possession is nine-tenths of the law.”

Now he was throwing legal theory at me — and fractions on top of that — but I somehow managed to grasp the premise. As I understood him, if an item was lost and I was the one who found it, then it belonged to me. Automatically. I was puzzled for a while, because this tactic had never worked inside our home. If I ever came across so much as a nickel in my older brother’s closet and taunted him with “Finders keepers, losers weepers,” he’d have stuffed me inside one of his shoes and left me there to die. The key difference, I eventually realized, was that the rule applied only to things discovered outside the house.

The next day, I shared this new information with my friends. One boy claimed to be familiar with it. “Yeah, no kidding,” he said. “Possession is nine-tenths of the law. Everybody knows that.” But the rest of them were happily surprised. The rest, that is, except for the lucky stiff who’d spotted and snared that five-dollar bill. We heard that he’d already bought an island in the Caribbean, and was no doubt lounging by his pool at that very moment, being fanned by one of his butlers and eating entire bags of potato chips and boxes of Milk Duds all by himself.

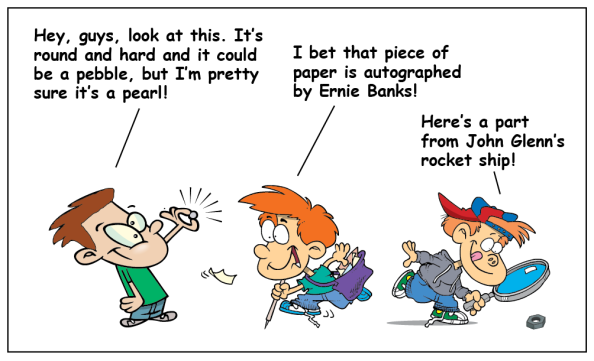

Recognizing how quickly wealth could be acquired, and sure that if such treasure could be stumbled upon by someone who couldn’t pass a third-grade spelling test, we concluded that the opportunity must be available to us, too. We began to devote every spare hour to scouring the ground, which was convenient because we were little, and so our focus tended to be downward anyway, where things were easier to reach.

In the process, we became experts in the nuances of litter, and dirt. Flattened beer cans could be used for first and third base in stickball, with manhole covers serving as second and home. When the ball rolled down a sewer, which it did every single time we played, we’d find pieces of tape or wire and create a recovery implement that could be lowered into the cool, damp opening. Bottle caps would be hoarded, as though we expected them to assume actual worth if collected in large numbers. We’d pick up old combs, broken glass, flat wooden ice cream spoons – anything that could someday be used to scrape, sharpen, or hang an important object.

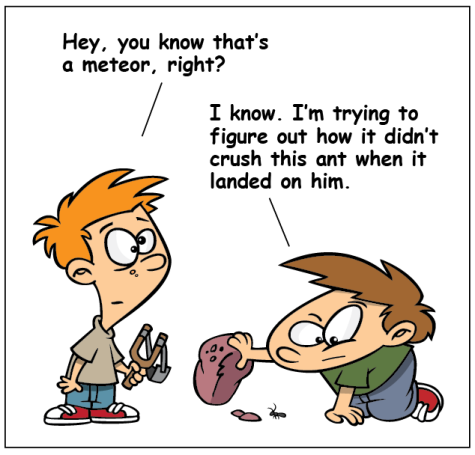

Our most exciting discovery, by far, were the meteors. These were dark gray rocks, typically the size of a grapefruit, with blue streaks swirling around holes and indentations. We’d cradle them in our hands as if they were sacred relics, the way you might hold a pouch containing the bones of a saint, or a Whitey Ford rookie card.

Our most exciting discovery, by far, were the meteors. These were dark gray rocks, typically the size of a grapefruit, with blue streaks swirling around holes and indentations. We’d cradle them in our hands as if they were sacred relics, the way you might hold a pouch containing the bones of a saint, or a Whitey Ford rookie card.

We’d find the meteors, usually by stepping on them, in the weeds outside the lace factory across the street. They weighed next to nothing, like dried sponges, and why they always landed right there, we didn’t even bother trying to imagine. But the idea that we could touch something that had once been flying through outer space almost made our brains melt. It never occurred to us that maybe they weren’t really meteors. More likely, they were pieces of burned fuel — probably coal – from the factory. An older boy from the neighborhood had suggested as much, but we suspected that he was just jealous, and secretly wanted to make off with our rare artifacts so he could sell them to the Museum of Natural History and buy his own island in the Caribbean.

In the many years that followed, I’ve grown a little taller, but have maintained that habit of scanning the ground for discarded riches. Not once have I ever found more than thirty-five cents, and that was at the car wash. I’m pretty sure the coins fell out of my own pocket while I was vacuuming the floor mats.

I’ll keep looking, though, because you never know what’s underfoot, or what might fall out of the sky. I still dream of that dealership, and the lifetime supply of bubble gum. The prices of both seem to have gone up considerably since our carefree days in the North Bronx, along with the value of those long-lost baseball cards. I only wish I could say the same for my bottle cap collection.

I am M.C.N - @cliveshome

February 7, 2014

We all have good memories growing up, even an abused child laughs sometimes. Having money is lovely, especially when you can buy something which all of your friends can share with you. At least for that moment your the best friend of all.

@cliveshome – The worlds Bankable poet.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2014

One of the things I miss about childhood was how little it took to feel happy or excited. It’s still possible, but it takes more of a conscious effort now.

LikeLike

Stacie Chadwick

February 7, 2014

Charles,

Your childhood memories make me wish for the days sans anything that starts with a lower case i followed by a capital T.

Thanks for starting my weekend off the right way.

Stacie

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2014

I know what you mean, Stacie. I just don’t understand why we have to choose. Why can’t we have amazing technology, solid values, and personal connection, all at the same time?

LikeLike

Lucy

February 7, 2014

You grew up in the Bronx? You poor thing. I grew up in Connecticut but when I was a teen my folks would send me to visit my cousins in Brooklyn for a couple of months in the summer. I loved it. I really liked your post. Lucy

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 7, 2014

The Bronx was exactly like Brooklyn, only a million times better.

LikeLike

Diane Henders

February 7, 2014

I found a $20 bill in a mall parking lot years ago, and to this day I feel guilty about keeping it. Twenty bucks! I wasn’t a kid at the time, which is why I felt so guilty – I could imagine all too well the impact on my groceries if I’d lost twenty bucks. I even went to the lost-and-found and asked if anybody had reported losing some cash. They looked at me as though I was a freak (okay, I was/am a freak, but that’s beside the point).

I think life must be easier for people with no empathy or imagination…

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2014

You are a freak, Diane, but an honest and good-hearted one. That’s the best kind. By the way, I lost twenty dollars once at a mall. I’m pretty sure it was somewhere in Alberta.

LikeLike

Diane Henders

February 8, 2014

The cheque’s in the mail…

LikeLike

ranu802

February 7, 2014

when could one buy an island for five dollars? Then again there was a time when you could occupy a lot of land by running,and you didn’t have to pay a dime.

I always look forward to reading your post,they are so interesting.Thanks.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2014

I may not have remembered that island part accurately, Ranu. Actually, the boy was back in school the following Monday. He just wouldn’t talk to any of us.

LikeLike

Lola Rugula

February 7, 2014

Long ago, on my 21st birthday, while celebrating at a club (of course) I came across a $20 on the dance floor, and then a $10, and later another $20. Never, ever again has something like this happened to me, but I still tend to scan the ground whenever I’m in a crowd. I wonder – did your friend ever come back from his island in the Caribbean?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2014

You found fifty dollars all at once? I bet there was someone there that night who’s never gone dancing again.

About twice a year, I have this dream that I’m finding coins on the ground. It’s two or three at first, but the more I look, the more coins there are. In the dream, I always think, “Wow, I’ve dreamed about this so many times, but now it’s really happening!” And then I wake up.

The part about the Caribbean island may have been a slight exaggeration.

LikeLike

Lola Rugula

February 8, 2014

Ha! Yes, I figured the island was an exaggeration, but I was holding out hope. I read that dreaming of finding coins is a sign of missed opportunity…maybe you’ll have to see if that rings true. I’m sure there’s a zillion meanings for it!

LikeLike

Mikels Skele

February 7, 2014

I got a dollar a week, and whatever I could make mowing lawns and shoveling snow. I once bought a brand new baseball, without any tape or anything; it’s as close as I ever got to an island, unless you count the old radio parts gleaned in the alleys, which we were sure were built specifically for kids. You New York kids got all the breaks!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2014

A brand new ball — was there anything better than that?

LikeLike

Chichina

February 7, 2014

I could relate to almost everything you wrote about. As kids, the potential of finding treasure in the dirt was ever present. I spent hours picking through stones in our driveway, convinced I was going to find a nugget of gold, or even a rough cut diamond. What we considered treasure as children would be considered garbage by kids today, although to do so they’d have to actually go outside and play. I love reading your recollections from the past. They are treasures worth holding onto.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2014

We used to find rocks that we were sure was gold. It was most likely pyrite, which my mother and father both referred to as “fool’s gold.” I was always disheartened by my parents’ ignorance about things like geology and precious metals. And yet, I listened to them. I could have been a billionaire today.

If it makes you feel any better, I did see a little boy outside just the other day. He didn’t seem to be playing, though. I think he was on his cell phone.

LikeLike

Chichina

February 8, 2014

Yes. The fool’s gold. I should have stock-piled it.

LikeLike

suburbanlife

February 7, 2014

Meteors = bones of saints = Whitey Ford rookie card. Love the comparisons which show a child-like magical thinking tendency. A ‘life-long supply of bubble gum” and buying a Caribbean Island where one lounges back eating potato chips indicates we are hard-wired to have pie-in-the-sky wishes and ambitions that lead to a love of gambling and the buying of lottery tickets. So, it seems we never do outgrow that.

I do wonder if your “meteors” might not have been handfuls of hardened lint. But isn’t it amazing how children imagine outlandish possibilities when finding a novel bit of detritus?

Lovely post! G

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2014

Not hardened lint. These were definitely rocks of some kind. They had the look of something that burned as it fell through the atmosphere, but I now realize they were almost definitely burned right here on Earth, probably inside a furnace.

I think you’re right about gambling, which clearly includes the purchase of lottery tickets: we’re excited by the possibilities.

LikeLike

Margo Karolyi

February 7, 2014

My sister and I used to walk up the main street (we lived at the far end of town) looking for dropped coins under every single parking meter. We found lots of pennies (no one bothered stooping down to pick those up), the occasional dime (which the owner probably mistook for a penny) and quite a few nickels (which got you 30 minutes of time on the meter back in the late 50s). Once we even found a quarter! Conveniently, the (penny) candy store was at the other end of town; we always had at least a few cents to spend.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2014

Most of that candy is still around, but now the pennies are gone. At least in Canada.

LikeLike

Margo Karolyi

February 9, 2014

Yes, you can buy most of it at the bulk food stores but I bet you wouldn’t get 3 mo-jos or 3 double bubble or 3 ‘black babies’ for a penny (even if anyone accepted them anymore!)

LikeLike

shoreacres

February 7, 2014

Right this very minute I’m looking at something I dragged home from a trip to the Texas hill country. It was just after Christmas. I was hoping to buy “this” or “that”, and couldn’t find either item, anywhere. Then, walking along the banks of Cypress Creek, I found “it”. The experience was just as wondrous as the ones you’ve written about here, and another reminder that keeping our eyes open not only helps us to find “stuff”, it helps keep us young at heart.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2014

Linda, just three days ago, I tried to watch a movie called It Could Happen to You. It was an old VHS tape that I’ve watched several times, but suddenly it wouldn’t play correctly. Yet Sinatra’s “Young At Heart,” which was part of the soundtrack, came through loud and clear.

At first I thought the “it” that you found was the tumbleweed, but it seems that happened well before Christmas. Your secrecy about the object tells me you must have written about it, or plan to. I’m heading over to your blog to see if I can find out.

LikeLike

nailingjellotoatree

February 7, 2014

I feel positively rich, we found $40 at the park this summer! I spent weeks imagining how I would spend it. Eventually we just bought groceries with it.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2014

Our son finds money all the time. It’s actually a little scary. And annoying.

LikeLike

thecontentedcrafter

February 7, 2014

I love the imagination of the kid you were – the utter belief that anything was possible and it would happen to you! [I think many kids these days miss these opportunities by being kept ‘safe’]. I still believe anything is possible 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 9, 2014

I agree, Pauline. There’s a wide range between neglect and over-protection, and completely safe isn’t always the best choice. We seem to have become terrified of anything that might happen. Learning and growth require some risk.

LikeLike

souldipper

February 7, 2014

For 40 years, I’ve faithfully hoarded a broken necklace that is most certainly a topaz which is far more valuable than the pedestrian and lowly citrine. And the intricate enamel work in it’s fragile frame could only have been created by someone featured in the Met or the Tate.

Charles, you bring out my folly – too easily! XO

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 9, 2014

I’m sure there’s at least one story in that necklace, Amy.

It’s great to hear from you.

LikeLike

Jackie Cangro

February 7, 2014

My dog found $1 on the sidewalk. Unfortunately he ate it before I could get to him. 😛

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 9, 2014

Still a cheap meal, if you think about it.

LikeLike

eobonyo

February 8, 2014

I picked 5000 shillings (about $2) in Primary 6 and lost 11000 shillings that same term. I think I’ll write a blog about it.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 9, 2014

I look forward to reading it.

LikeLike

bitchontheblog

February 8, 2014

I like your father – and shall remember him next time I take my card from the cashpoint only to walk away without the 50 Pound Sterling I had just requested. I am sure the finder was happy.

Yes, Charles, bronxyboy, we Europeans have a rather romantic notion of the Bronx. Violence and all that. To think you grew up there doesn’t make much sense considering your unique selling points but – no doubt – made you into the hoot* you are. Meaning I time my reading of your posts carefully. When in need of a laugh …

U

* ‘Hoot’ – English, informal – an amusing person or thing

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 9, 2014

Too bad the next customer was a dishonest person, Ursula. It would have been so easy to figure out who had made the withdrawal, and return it to her. I’d like to think that’s what most people would do.

LikeLike

Snoring Dog Studio

February 8, 2014

I’m relieved to know that another adult, and not a homeless one, scans the ground for stuff. I come from a long line of scanners. I don’t find the riches here that I used to in Minnesota, however. I discovered this fact, after years of living through Minnesota winters — a lot of stuff is dropped during a snowstorm and lost to their owners. If you’re the early bird and get out there during the first thaws of spring, you can reap quite a bounty. I did. I found expensive sunglasses, money, jewelry, construction tools — all sorts of neat stuff. One early Saturday morning in Minneapolis, I was walking and scanning through one of my digs – the parking lot of the strip mall — and I spotted an old lady with a walker, doing the same thing. I marched over to her and told her to beat it and that this was my territory. And I kicked her walker out from under her for good measure.

I didn’t actually do that. But I thought about it. I found 20 bucks one day here on the way to work. I felt real guilty about it but I figured the person with the 1/10th of the law on their side would have been taught a good lesson.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 9, 2014

Jean, I recently lost a prized keychain, and I’m hoping I’ll find it when the snow melts. Then again, the snowplow may have already scooped up the keychain and delivered it to a neighbor ten houses away.

Am I the only person who’s never found twenty dollars?

LikeLike

Snoring Dog Studio

February 9, 2014

Sorry about your key chain. Bummer. You have to accept that if you become a scanner, your loss will also be scanned as well. As far as the twenty bucks – here’s a tip: check around ATMs. I mean, don’t put your hand up into the cash slot or hold up some dude getting beer money; look on the ground around it. Sheesh. You amateur.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 9, 2014

I’m not an amateur. I’m what the gangsters call a small-time operator. I used to hang around the toll booths on I-95. People are always dropping money there, and it rolls under their car. But it’s a dangerous business. After the third time I got run over by an eighteen-wheeler, I decided to call it a career.

LikeLike

Snoring Dog Studio

February 9, 2014

Learning through experience isn’t always the best teacher, eh?

LikeLike

georgettesullins

February 8, 2014

I rather like the spirit of Russell Wilson, all 5’11”, 206 lbs. of him, a light weight they say in the NFL. “Why not you?” his dad would ask him. “Why not me?” carried him through his career. And, “Why not us?” perhaps won the SB. For him it applied to his career, for the rest of us not in the NFL, we can fill in the blanks.

Once, a drive through teller gave me more money than my withdrawal slip indicated. I saw a young lady who had to have her teller box come out right at the end of the day. Yeah, at the end of the day, I had to call her attention to her error.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 9, 2014

Nice story about the teller, Georgette. Once you consider the potential harm and weigh it against the possible benefit, it isn’t hard to know what to do. Still, would most people do what you did?

LikeLike

silkpurseproductions

February 8, 2014

We had a wonderful place when I was a kid called, “The Car Banks”. It was like a small abandoned valley that seemed massive in those days. We would spend hours searching for treasures there. Our imaginations were much like yours. Everything we found was bigger, better and more important than its reality and we had great fun fantasizing the stories. I had a glass collection and every beautiful colourful piece was found there. I wish I still had my box of broken glass bits. I would make something crafty from it.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 9, 2014

Why was it called the Car Banks?

LikeLike

silkpurseproductions

February 9, 2014

After you jolted my memory about it I asked about it in my “If you grew up in Niagara Falls you will remember…”. It turns out that the bottom of it followed an old trolley car line and I do remember there being tracks at the bottom. Apparently the tracks have been removed and it was filled in years ago. People probably live on top of it now. It was the best tobogganing in the winter as well.

LikeLike

icedteawithlemon

February 8, 2014

In the mind of a child, can there possibly be any reward greater than a life-time supply of Bazooka Bubble Gum? I love when you write about your childhood memories because I am reminded once again that, despite our differing backgrounds, we are all so similar on a fundamental level–and if we could all become grown-ups who still focus on those similarities rather than the differences.

ANYWAY … somewhere in my basement I have boxes of rocks that my little girl self was sure were arrowheads, fossils and diamonds. I also have a large, round rock that my own little boys found in our woods–a rock they were convinced was a fossilized dinosaur egg. My oldest son took it to his science teacher for confirmation, to which the teacher responded, “No one around here can prove that it’s NOT a dinosaur egg.” Exactly. Dream on, little ones.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 10, 2014

What a perfect response by your son’s science teacher, and something I suspect you would have said to your student, too.

LikeLike

upsidediy

February 8, 2014

I am reminded of a small lot across the alleyway from a bar I pretty much grew up in. During the spring sour grass flowers would bloom. We would pick them and chew at the tartness as we searched the lot for lost treasures. We’d lay on the grass and look up towards the sky and imagine the big puffy clouds as animals that would come down and take us up for rides. Maybe take us away somewhere better. And ahhh penny candy. My brother and I could buy a small brown paper sack full of penny candy with the left over change from buying awful cigarettes for adults too lazy to walk to the store themselves. But we didn’t think of it as lazy back then. Side by side my brother and I would skip to the store, avoiding the cracks in the sidewalk for fear of breaking our mothers back. As for the bazooka gum; not very good gum but the excitement of something funny inside was worth risking sore jaws! As always you conjure up memories for me and somehow I can see the beauty in parts of an ugly childhood. I thank you. This is Koko btw… my other blog. 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 10, 2014

It sounds as though we had similar childhoods, Koko — right down to the adolescent walks to the store to buy cigarettes for grown-ups. But the bubble gum issue is relative. Bazooka was delicious when compared to those pink, sugar-dusted wafers that came in packs of baseball cards.

The link to your DIY blog doesn’t seem to be working.

LikeLike

upsidediy

February 10, 2014

Uh oh…I will check on the link. I agree with you about the baseball cards. Do you still have them? The cards that is, not the candy. Hehehe.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 10, 2014

I wish.

LikeLike

upsidediy

February 10, 2014

And on the Upside…It’s more important that I follow you, as to not miss out on any stories! Have a fab Monday!

LikeLike

Choosing

February 8, 2014

Here you see a lot of (mostly older male) people walking around the beach with metal detectors … I have never asked any of them if they have ever found anything useful… I imagine it is a lot of bottle caps and maybe pens or broken sun glasses… But at least they keep the beach clean – or I am being too optimistic in assuming they will put the trash in a bin instead of throwing in back in the sand?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 10, 2014

I always admire those metal-detector guys. They seem to not care how weird they look. But my guess is that they’re picking up only what they intend to keep.

LikeLike

Kathryn McCullough

February 8, 2014

I remember “finders keepers, losers weepers.” My dad was ridiculously generous, so he never said it to me, but my siblings and I said it to one another.

Hope you’re having a wonderful weekend!

Hugs from Ecuador,

Kathy

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 10, 2014

You and your siblings must have been close in age. That saying doesn’t work when you have to look straight up to see your brother’s face.

LikeLike

daisy

February 8, 2014

Charles, you nailed it with this line, “After all, anyone who lost that much money would be out there with a sickle in one hand and a shotgun in the other.” It speaks, like your entire post, so perfectly to the immediacy of childhood dreams. I could see you and your friends out there, fishing for lost balls with bits of twine, and shoving bottle caps into your pockets. I could see it all — great post.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 10, 2014

Thanks, Melissa. Sometimes I’m amazed at how vivid those memories are, especially when I struggle to remember much more significant things that happened much more recently.

LikeLike

jeanjames

February 9, 2014

When I was a kid we used to go up to the Adirondack’s where my Uncle had a cabin in the woods. Nearby were these old abandoned rail tracks used during the Olympics to get back and forth to Lake Placid (at least that’s what I was told). In between the tracks was a treasure trove of fossil rocks that I would spend hours sorting through impressed with my rich collection. I thought for sure I was the next great archaeologist. Those rocks are now a valuable reminder of my childhood, as I’m sure your weird rocks are to you.

BTW I once found a $100 bill on the floor of a dance club. It was folded up and I thought it was a dollar, you can imagine my surprise when I opened it up…drinks on me for everyone that night!!

Great Post!!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 11, 2014

…old abandoned railroad tracks. That sounded like something from the 1800s. I remember the Lake Placid Olympics, and very clearly. I thought you and I were about the same age, but I guess not. And did you really find a hundred-dollar bill? If so, I think that makes you the winner.

LikeLike

jeanjames

February 12, 2014

I was 10 in 1980…I’ll leave you to do the math. Honestly being in the middle of nowhere on tracks that carried nothing in a cabin with no electricity, a hand crank for a well pump, and an outhouse was exactly like being in the 1800’s lol.

And yes I really did find a $100 bill once, but I also lost just about as much so I guess the universe keeps me in balance…it’s the crux of being a Libra.

LikeLike

earthriderjudyberman

February 9, 2014

I still spend most of my time looking down – for treasure – rather than up. I haven’t amassed any wealth to speak of, but I’m sure one day I will. 🙂

When my girls were young, I lost a $10 bill outside a Burger King we’d just entered. Thank heavens for the honest soul who returned it to us. It was my last $10 until pay day which was at least a week away.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 11, 2014

It’s interesting how a lost ten-dollar bill can become a happy story, yet not losing it would have produced no feelings at all.

LikeLike

stephrader

February 9, 2014

I always collected the spare nuts and bolts and “parts” I came across on the ground, convinced they would all come together and build an amazing gadget or robot one day.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 11, 2014

That still sounds like a good idea. I hope you haven’t given up on it.

LikeLike

reneejohnsonwrites

February 10, 2014

I like to find wishing stones – those cool grey rocks with white stripes around them. But you have to throw them as you make a wish. So they didn’t collect around the house although I wasn’t above saving one for just the right wish…

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 11, 2014

I’ve seen plenty of those, but I never knew they were called wishing stones.

LikeLike

reneejohnsonwrites

February 14, 2014

I bet you’ll be collecting them now! Your dreams could all be one wishing stone away! You never know.

LikeLike

ShimonZ

February 11, 2014

charming article

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 16, 2014

Thanks, Shimon.

LikeLike

rangewriter

February 14, 2014

If kids today could take scrounging as seriously as you guys did, we’d solve the litter problem!

This reminds me of the first weekend after my retirement. This happened to also be a home football game weekend and I live very near the campus.Early Sunday morning my friend and I bundled up to walk into town for brunch. As we approached the campus, I said, “Keep you’re eyes open, ya never know what falls out of the cold hands of drunks on their way home from the game.”

He was about to scoff at my notion, when my eye caught a bit of green poking out of the brown leaves in the gutter. I bent in glee and interrupted him, “just like THIS!” and I held up my $20 prize. He was astonished, to say the least. Even accused me of planting it. I frequently walk the streets between my house and campus and my eyes are always skimming the ground. I haven’t found any more twenties, but I’ve found lots of change and a few ones and fives. Nice little post-retirement bonuses. 😉

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 16, 2014

It’s interesting how we all remember these unexpected finds, Linda, no matter how recently or long ago they occurred.

LikeLike

anntogether.com

March 3, 2014

When I was no taller than my mother’s hip I found a half of a dollar-literally it was a dollar bill ripped in half. I rolled it up and attempted to purchase Crayola’s Box of 64 Crayons. I handed over the rolled bill and ran with my crayons. No sooner did I get to the glass doors then the cashier was after me and so was my mother. I took a beatin’ then my mom wacked me on the head too. 😉

Great blog – humor is the only power vitamin on the planet. Thank you for sharing.

AnnMarie

newbie blogger

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 26, 2014

AnnMarie, I apologize for the late reply to your comment, but I just noticed it. I remember occasionally finding half a dollar bill, too, and wondering if it would be accepted at stores.

Good luck with your new blog.

LikeLike

anntogether.com

March 26, 2014

No worries, I wonder how anyone keeps up with any of this blogging now that I’ve gotten my feet wet in the business that is blogging. Lots o’work. Thank you 🙂

AnnMarie

LikeLike