There are these people called paparazzi. It’s a word that always makes me think of Italian police cars, or small deep-fried desserts. But, no, they’re actually human beings. They can also be thought of as punching bags with zoom lenses.

There are these people called paparazzi. It’s a word that always makes me think of Italian police cars, or small deep-fried desserts. But, no, they’re actually human beings. They can also be thought of as punching bags with zoom lenses.

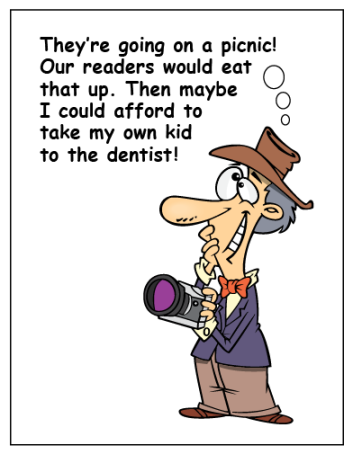

The paparazzi would prefer to be called photo-journalists, I imagine, but that makes it sound as though they’re covering major elections and summit meetings and tornado damage, and that isn’t what they’re doing at all. Actually, these people chase celebrities – mostly movie stars and famous athletes – for the sole purpose of getting a picture of them doing something irresistibly fascinating, like driving their kids to school or buying a loaf of bread. When they get some really good shots, they can sell them to magazines for thousands of dollars. If they happen to snag a popular actress, either holding her young baby or carousing on a secluded beach with a married politician, that can translate into millions.

Meanwhile, the subjects of these photographs try their best to elude the paparazzi, even as they crave the accompanying attention and publicity. One of the reasons for this seems to be that the very act of pretending to avoid the media glare causes even more of it. There’s little that arouses our curiosity like someone complaining about an invasion of their privacy. This is especially true for the idols of our modern culture, who seek to protect their personal lives by explaining, in front-page interviews and on late-night talk shows, how traumatic their recent psychotherapy sessions were in that awful rehab facility, an experience that forced them to re-live the horrors of a childhood filled with physical abuse and wild, drug-fueled parties.

The driving force behind all of this is the same thing that causes a coin collector to salivate at the sight of a 1916 Mercury dime, or a Russian oligarch to lose his mind and bid a tenth of a billion dollars for a painting of a man with bad posture seated on a wooden chair, or one of us to wait in line for six hours outside a Target so we can buy the latest iPhone. It’s simple supply and demand. If a thing is rare, or even if we just believe it is, we want it. And the more people want something, the higher the price will go.

In the case of the actress and her newborn, we’ll never get to see them in person. We weren’t even invited to the baby shower. But if some crummy magazine has a picture of them, we’ll shell out four dollars to see it, especially if we’re at the grocery store and feeling kind of delirious because we just found a coupon for a free box of Hamburger Helper. And it matters little if the image is black-and-white and out of focus, and was taken from under a pile of leaves. If the caption says it’s them, that’s good enough for us.

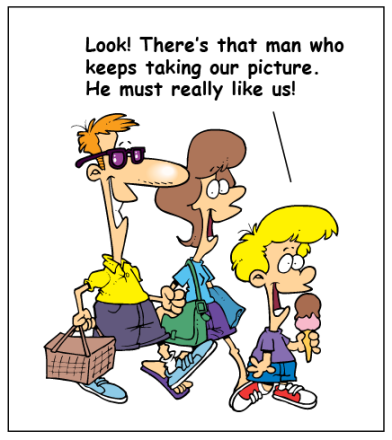

It isn’t hard to understand why this makes the celebrities mad. When I’m at a show with my family and some hack photographer takes our picture in the lobby of the theater, I get pretty annoyed. Okay, not so much that they took the picture, but that they now want me to pay sixty dollars for a blurry five-by-seven in a cardboard souvenir frame. Okay, not so much the price or the cardboard frame either, but the fact that I’m the only one in the group who doesn’t want it, and that I end up going back to buy the stupid picture out of guilt. I’m also afraid the hack photographer will leave the unwanted print taped to the wall, where hundreds of theater-goers will later stroll by and wonder why I have that irritated look on my face.

It isn’t hard to understand why this makes the celebrities mad. When I’m at a show with my family and some hack photographer takes our picture in the lobby of the theater, I get pretty annoyed. Okay, not so much that they took the picture, but that they now want me to pay sixty dollars for a blurry five-by-seven in a cardboard souvenir frame. Okay, not so much the price or the cardboard frame either, but the fact that I’m the only one in the group who doesn’t want it, and that I end up going back to buy the stupid picture out of guilt. I’m also afraid the hack photographer will leave the unwanted print taped to the wall, where hundreds of theater-goers will later stroll by and wonder why I have that irritated look on my face.

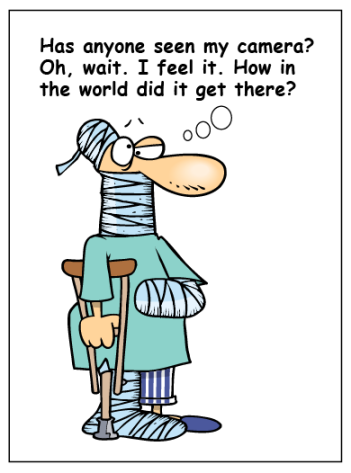

I wandered off track there. My point is that the celebrities claim they don’t want their pictures taken and published without their consent. They especially don’t like strangers following them to the bank, or hiding in the bushes outside their twelve-thousand-square-foot mansions. Many of them resort to violence, punching the stalkers and destroying their camera equipment. The result is the ridiculous spectacle of a red-faced actor swinging wildly at a man with a tripod, all recorded onto film by other photographers who had managed to maintain a slightly safer distance. And yet, it’s the self-promoting behavior of the celebrities that causes the demand for those pictures in the first place. After all, it’s difficult to get attention, and relatively easy to lose it. Most consumers get bored pretty quickly.

And that’s the solution to the problem of persistent paparazzi.

If there were an abundance of the photographs, they wouldn’t be worth anything. As a world-famous celebrity wishing to guard my privacy, I would flood the market. I’d take a few dozen pictures of family outings – trips to the hardware store, parent-teacher interviews, oil changes – plus some special events, such as weddings, birthdays, and school concerts, and I’d mail them to every newspaper and magazine in existence. I’d also send them, at my own expense, to television entertainment programs. I might even print up some flyers of our newborn – or just some newborn, because really, who can tell? – and nail them to telephone poles and hand them out on street corners.

Soon, and probably almost immediately, the recipients would ask me to stop distributing the unsolicited images. They’d put my name on a list of subjects they’re not interested in, and will no longer pay for. The increased supply would reduce, maybe even eliminate, the demand.

Then I’d be able to go out in public, free to roam the streets, undisguised and unbothered. There’d be no need to punch anybody, or make a scene. I could even go down to my favorite bakery and pick up a box of those delicious, deep-fried paparazzi. That is, if I really wanted to.

anthonymanson

January 6, 2014

Reblogged this on anthonymanson.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 7, 2014

Thank you, Anthony. I’m glad you liked it enough to re-blog.

LikeLike

ArborFam

January 6, 2014

I always feel a little like a celebrity when I go to an amusement park and have to fight off sweaty, desperate young people with cameras shouting at me to get my picture taken to memorialize this significant moment in my life. Even the Columbus Zoo has these young people prowling the entrances. I have often wondered if they get paid by photo taken, photo redeemed or on some pro-rated basis taking into account how beautiful the subjects are and how happy they look.

If you’re ever in the market for a picture of me and my family at an amusement park, I have a bunch I could let go of for way less than a million dollars.

Happy New Year, Charles!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 7, 2014

I would think they get paid only for the photos that are purchased.

At some amusement parks, they have cameras mounted at key positions on some of the rides, and the pictures are taken automatically. The results are always photos that you’d eagerly share with everyone you know, especially the ones that show you soaked, screaming, and biting your own fist.

Happy New Year to you, too, Kevin.

LikeLike

Chichina

January 6, 2014

OMG, I’m sitting at my desk with my door open and I guffawed out loud. You kill me.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 7, 2014

Thanks, and Happy New Year. I hope you’re doing well.

LikeLike

Kathryn McCullough

January 6, 2014

Brilliant! Why have the celebrities not come to realize this on their own? Flood the market!

And I, too, have lots of bad photos I’d be willing to share–with you, hell, with anyone. Give me a few bucks–they’re all yours.

LOVE it. Hilarious post!

Hugs from Ecuador,

Kathy

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 7, 2014

Kathy, I’ve given this topic very little thought, so I have to believe the hounded celebrities must have come up with this solution long ago. The successful ones know how to keep themselves in the spotlight — and they get to whine about it at the same time.

LikeLike

subodai213

January 6, 2014

You’ve absolutely put your finger on the celebrities. They want that attention-they’re Actors, for heaven’s sakes, and an actor (or -tress) is that because they are ‘self-promoting’ and, may I say, in most cases, narcissistic. The older and more famous they become, the more the seem to believe their own hype and publicists. So why do they become upset when paparazzi take their photos? Because they one, aren’t making money on it, and two, the photos shows them sans makeup, sans tight clothes, sans pretty arm candy, etc. It shows them as paunchy, balding men or droopy boobs and turkey necked women. Have you ever seen a paparazzi shot of Tom Cruise without his makeup? He looks like a leopard. He has freckles everywhere.

I treasure my anonymity. I don’t mind being just ‘another face in the crowd’. I don’t like being in someone’s camera range, but I also know that I’m not the subject of the photo, and will probably be cropped out when the photographer photoshops it. The nice thing about being nobody – in the movies, the actress or actor is always the one being chased by the bad guys or the T. rex. The rest of us nobodies ran like hell when they showed up and survived.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 7, 2014

Your last sentence reminded me of all the movie scenes in which the main character is being pursued in a high-speed chase. There could be a hundred-car pile-up, but as long as the hero survives, we’re not supposed to care how many innocent victims there are. It’s thrown right into our faces that the celebrity’s life is more important than ours, and we eagerly pay to see more.

LikeLike

Wyrd Smythe

January 7, 2014

Something I’ve noticed in the last five or so years: many chase scenes include quick shots designed to let you know that no one was (seriously) hurt. Watch for quick cuts of the cops in the overturned cop car gingerly climbing out, camera angles designed to show people quickly leaping out of the way, etc.

This does not include that mindless movie crap where entire downtown buildings are destroyed. Funny how quickly we forget Oklahoma and 9/11 and turn it into more grist for the “entertainment” mill.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 8, 2014

I get pretty bored with car chases, so I tend to avoid those kinds of movies. But I’ll have to pay closer attention when I find myself unexpectedly watching a chase scene. The downtown explosions always make me think, “Wait a minute, didn’t about a thousand people just get killed there?”

LikeLike

Wyrd Smythe

January 8, 2014

More and more I find myself thinking similarly. For me it really ramped up with the Lord of the Rings movies. Yes, it’s all CGI and stunts, but if I suspend my disbelief and believe in the story, then I’m watching a story in which many thousands of people (or in this case, beings) are being casually slaughtered… for my “entertainment.”

It’s one thing to read about a horrific battle scene in a book, or to have it sketched out in a live play or even to see it on-screen with cheesy effects. There’s a strong sense of disconnect that makes it a story (or history). But modern film technology can make it all look utterly real, and I think that’s part of the problem. It connects with us viscerally, and we end up living inside the violence.

And it’s well understood that that kind of exposure to violence absolutely desensitizes one to it and makes violence into part of one’s “language” for handling the world.

LikeLike

nerdinthebrain

January 6, 2014

Another fine idea you’ve had! 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 7, 2014

Thank you, Nerd. Glad you liked it.

LikeLike

shoreacres

January 6, 2014

And then we have the “selfie” – the last refuge of the celebs, politicians and once-famous now ignored by the paparazzi. No matter how vehemently the ones being followed complain, attention is a high, and when they’re deprived they’ll do whatever it takes to regain the spotlight. When they begin protesting about all the attention they’re receiving? I’m with Shakespeare – methinks they doth protest too much.

LikeLike

subodai213

January 6, 2014

You’ve got that right. They’ll do anything to keep that spotlight of attention on them, good or bad. Witness that girl who used to be with Disney…I’m waiting for her to do something nasty with an armadillo on stage, no matter how low taste it may be. Oh, yeah, Miley Cirus.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 7, 2014

Paris Hilton seems to have disappeared, and I still haven’t figured out who she is. Maybe a short attention span has some value after all.

LikeLike

perspectivesandprejudices

January 6, 2014

Haha! Hilarious post and so true! 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 7, 2014

Thanks for the nice comment.

LikeLike

ranu802

January 6, 2014

Yes Paparazzis do make a lot of money by taking pictures of celebrities. I think what they do is terrible. I wonder who pays thousands of dollars to get those pictures. These guys are useless.

Once again Your post is hilarious.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 7, 2014

But the consumers are the ones who determine the value of those pictures. Ultimately, the thousands of dollars come straight out of our pockets.

LikeLike

Betty Londergan

January 6, 2014

Now I know exactly what to do when I get obscenely famous and everybody is dying for any and all photos of me …. or my family …. How ridiculous is this paparazzi thing anyhow?? Have you seen the column that says … Celebrities are just like you & me — and then they proceed to show them buying bread or crossing the street. Like somehow, we never KNEW that. But do I pick up the magazine and thumb through it anyhow?? Of course. What a hypocrite I am!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 7, 2014

Fame seems to have become a goal in itself, Betty. I think that’s why we’ve lost the real concept of scandal. Being a household name — for almost any reason — now comes with rewards too alluring to resist.

LikeLike

silkpurseproductions

January 6, 2014

This does seem like a really good solution. It even seems like a fairly simple solution. So what would become of all those out of work really lousy example of human beings, the Paparazzi? Would they find some way even more despicable to earn money? Hopefully nothing that would harm non-celebrities.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 8, 2014

Maybe they could be hired to finally get some clear pictures of UFOs, ghosts, and Bigfoot.

LikeLike

icedteawithlemon

January 6, 2014

Excellent point! I wonder how many of those celebrities started out on “reality” TV shows–people who became famous for being famous . . . and can we hope the same philosophy will soon result in the demise of those shows as well? The demand was there for reality TV (although I certainly didn’t demand it–did you?), so the supply was increased, so much so that the market was flooded. And now, hopefully, this increased supply will also “reduce, maybe even eliminate, the demand.” And if not, maybe they can be deep fried in the same vat as those decadent paparazzi.

(And I HATE being made to feel guilty for not wanting those souvenir pictures in their cardboard frames. I’m usually the only one with my eyes closed, spinach in my teeth, and tea stains on the front of my shirt.)

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 8, 2014

The thing that always gets me about those souvenir photos is that they position you in front of a bad, flat mural of the place you’re visiting. If I want a picture standing in front of Niagara Falls, there should be some depth, and at least a little mist.

LikeLike

earthriderjudyberman

January 6, 2014

There are times when I think the paparazzi go too far … like using a telephoto lens (or whatever) to get shots of private moments while they’re up a tree outside the bedroom. Seriously, I also think of Princess Diana. That fatal crash was the result of overzealous paparazzi chasing after the car she was in.

But, Charles, you do make an excellent point. Flooding the marketplace with photos of yourself in every situation would certainly dampen the enthusiasm when there are no “exclusive” shots to be had. I think you ought to slap a patent on that and corner the market. 😉

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 8, 2014

I guess there will always be a market for the scandal shots, Judy — the blurry pictures of some governor prancing around with the blonde bombshell. (I don’t know why, but the woman is always described as a blonde bombshell. I think it raises the price by forty percent.)

LikeLike

Elyse

January 6, 2014

The paparazzi is completely responsible for the failure of my acting career. I couldn’t bear the idea of them in my face (and my life) at all times. Except for the delicious fried ones, they’re delish!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 8, 2014

Not to mention all those autographs you’d have to sign. It just isn’t worth it.

LikeLike

Julie

January 6, 2014

1) I think you should always buy the cheesy family photo especially if you are someplace special like the Great Barrier Reef (just do it) even if it will end up in your wife’s underwear drawer . . . forever, and 2) I always LOVE reading your posts!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 8, 2014

That picture of the GBR on your blog — did you take that? And what about sharks? (Who’s the worry wart now?)

LikeLike

Julie

January 9, 2014

Yes on GBR, but there were tears when I wanted the $16.00 cheesy photo of our whole family and everyone said it was a waste of money. Of course I got my way. Thanks for the reminder; I really need to get that family photo out of my dresser and into a frame.

LikeLike

Allan Douglas (@AllanDouglasDgn)

January 7, 2014

Your method of handling the invasive press (I use that phrase because i can’t spell paparazzi) is a great idea. Sadly it is not one I personally can employ. Well, I could, but there is no need. But should anyone I know ever complain about those guys I can’t spell, I’ll pass your suggestion along. Thanks for brightening my morning.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 8, 2014

Allan, maybe one of us should start a blog devoted exclusively to photos of paparazzi at work. We could get the celebrities to fund us and help us pay huge fees for the shots. Then the paparazzi would ignore everyone else and just take pictures of each other.

That’s it. After this, I’m never saying the word paparazzi again.

LikeLike

eobonyo

January 7, 2014

That’s a great solution right there. All celebrities should probably read it; but I bet the paparazzi won’t allow them to.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 8, 2014

We see the same faces over and over, even if we don’t want to. Obviously, many celebrities have figured out how to handle it, or somehow avoid the whole thing.

LikeLike

thewaywardsoldier

January 7, 2014

I love your blog! You have a delightful humour that is quite tongue in cheek !

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 8, 2014

Thank you. I appreciate that.

LikeLike

desertdweller29

January 7, 2014

I especially enjoyed when you went off track…

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 8, 2014

It’s one of those sneaky tricks of writing: You can get away with something if you’re the first one to point it out.

LikeLike

Barbara Rodgers

January 7, 2014

Great idea! I love the crooked eyeballs on the photographer in the last cartoon…

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 8, 2014

Thanks, Barbara. The original artwork for the cartoons was all done by Ron Leishman. Check out his website: http://www.toonclipart.com.

LikeLike

Diane Henders

January 7, 2014

I totally cracked up at the caption on that last cartoon! And I love the way you’ve analyzed the whole situation – it makes perfect sense to me now…

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 9, 2014

You may not believe this, but I thought of you when I was working on that last cartoon. I imagined you could have come up with something better.

LikeLike

Diane Henders

January 10, 2014

Aw, thanks! But nobody could top that – it was truly masterful!

LikeLike

cat

January 7, 2014

While you are going to your favourite baker, I’ll be going to my favourite butcher … meet you at the corner … then we’ll go to our favourite candle stick maker … Love your blog … Have I wished you Happy New Year yet? … Happy New Year, Mr. Bronx Boy … Love, cat.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 9, 2014

Happy New Year, cat. It’s always good to hear from you.

LikeLike

Diane Holcomb

January 7, 2014

Very funny. I especially like the line about deep-fried desserts.

As an actress, I understand wanting to be “known” (in my case) onstage. But offstage, personally, I don’t want to be the center of attention. It’s a strange dichotomy…many actors are actually shy. But give us some well-written lines to spout, allow us to emote onstage where it’s acceptable, and we shine!

That said, there are an annoying number of egotistical actors who crave the spotlight 24/7 and who keep the paparazzi in business. What a strange itch, our desire to spy on others!

Another five-star post! (out of five…er…stars)

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 9, 2014

I’m guilty of generalizing, I think. Many celebrities are no doubt shy, as you said, and it does seem to be the same few who are constantly shoved down our throats. Every time I see another magazine with Jennifer Aniston on the cover, I think she must be getting close to Joe DiMaggio’s hitting streak by now.

LikeLike

Wyrd Smythe

January 7, 2014

You may be seriously underestimating the public appetite for new photos and, in particular, specifically photos the famous people would rather you didn’t see. Humans are voyeuristic, gossipy, looky-lou busybodies, and there’s little else in the world so beloved as someone else’s troubles. Keeps our minds off our own!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 9, 2014

We’re definitely doomed. And that reminds me: I have to renew my subscription to People Magazine.

LikeLike

Stacie Chadwick

January 8, 2014

You’re right, who CAN tell when it comes to newborns? Before I read this I thought my child-bearing days were long gone, but your post got me thinking. Maybe I can have another baby and rent it out to C- level stars who don’t but totally do want to be chased by photojournalists. My baby could be the bait and I could pocket some serious cash for that mega-mansion. Or I could just take a nap.

Great read, as always, Charles. =)

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 10, 2014

Good idea, Stacie. But why not just buy some baby pictures from a stock photo company? A little less expensive, and a lot less painful.

LikeLike

rangewriter

January 8, 2014

Quick! Patent that idea! Surely it’s worth bazillions to the paparazzi beset! I love that last cartoon!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 10, 2014

It would only work if the supply goes up and the demand goes down. Given our celebrity-crazed culture, I don’t see that last part happening anytime soon. There are just too many of us willing to lavish our attention on the few who don’t need it. I compare it to sending a cash donation to Bill Gates or Oprah Winfrey.

LikeLike

rangewriter

January 10, 2014

That’s a really funny analogy!

LikeLike

Snoring Dog Studio

January 9, 2014

Loved this. And it is a brilliant solution to their problem. Or, “problem.” If they’re out in public, they’re fair game.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 10, 2014

Maybe it’s human nature to want all the benefits, without the drawbacks. All in all, their problem doesn’t seem that unbearable.

LikeLike

marymtf

January 10, 2014

Papparazi is a euphemism for ‘scum of the earth.’ One may avoid the magazines, but we have online blurb and photos now. Good thought, Charles but there’s no totally getting away from it.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 10, 2014

I know, Mary. You’re right. And it’s only going to get worse. But it was fun to think about.

LikeLike

You'll Soon Be Flying

January 10, 2014

You kill me! Ok, no really, you don’t. But if you were the paparazzi and I was a famous actress I’d let you hunt me down and snap a photo of me eating yogurt. That’s how much I love your blog! Great read, again!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 14, 2014

Thank you again. I appreciate the kind words.

LikeLike

charminghealth

January 14, 2014

Reblogged this on Wealthy Healthy Lifestyle.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 15, 2014

Thank you. I hope your readers like it.

LikeLike

Bruce

January 24, 2014

A good read Charles. I especially liked the part of the hack photographer in the theatre lobby selling by guilt. It may have been off track but it sent me back years to first time restaurant dates. Visiting rose sellers and photographers walked the tables spreading guilt on those who couldn’t stretch their teenage money to impress their girl. I didn’t like it then or now.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 24, 2014

The pressures and insecurity of young love. At least we’ve outgrown that. Haven’t we?

LikeLike

Sandra Parsons

February 6, 2014

I am glad you found the perfect way of dealing with paparazzi. It will come in handy when you are famous. (Note I didn’t say ‘if’!)

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2014

I’d have no idea how to become famous, Sandra, or what to do with fame if I ever found it. But thanks for the sentiment.

LikeLike