One day, when I was old enough to comprehend the words, but still young enough to be impressionable and immune to sarcasm, my mother made a startling announcement to me.

One day, when I was old enough to comprehend the words, but still young enough to be impressionable and immune to sarcasm, my mother made a startling announcement to me.

“I don’t have eyes in the back of my head,” she said.

She may have been washing the dishes at the time, or ironing shirts, or defrosting the freezer. Or maybe she was engrossed in the latest infidelity on Days of Our Lives, or trying to figure out which of the three contestants on To Tell the Truth was the real submarine captain. I was probably working in my coloring book, and asking her if I had picked the right shade of yellow for the canary, or an acceptable blue for Paul Revere’s hat. Whatever we were both doing, I had said something that compelled her to declare this physical limitation.

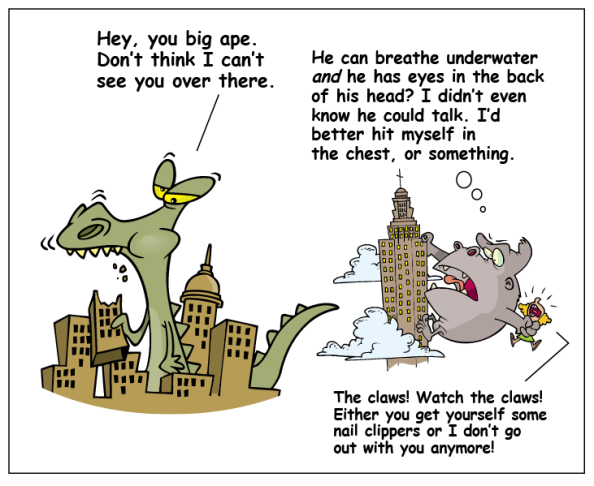

As usual, my struggle for a suitable reply was long and fruitless. I had never entertained the possibility that my mother might have another pair of eyes anywhere on her body; they certainly wouldn’t have done her much good beneath all that thick, black hair. In fact, it hadn’t occurred to me that anyone would have eyes in the back of their head. This was five decades ago, and I don’t think even the most terrifying monsters had such a feature. And that’s too bad, because it would have helped King Kong in his disagreements with Godzilla, who weighed fifty-thousand tons, had the ability to regrow lost limbs, and could exhale radioactive fire. Kong was tall for a gorilla, but he didn’t seem to have any special gifts, other than a tendency to beat his own chest — a pretty puny response to atomic breath, as far as I could tell. As with proofreading or searching for a dropped earring, when you’re up against a giant dinosaur that’s eating your city, a second pair of eyes can prove useful.

Some time after my mother’s unexpected admission, my teacher issued a related statement. However, its message was dramatically different, and was delivered more as a warning: “If anyone is thinking about trying anything funny,” she said, “remember that I have eyes in the back of my head.”

I believed her. For one thing, she was a nun, and nuns didn’t lie. For another, she was writing on the blackboard and was facing away from the class when she said it, yet somehow she seemed to sense that the girl to my right was bugging me to pass a note to the boy on my left. I didn’t know if Sister had thick, black hair because all the nuns wore a habit that covered their entire head. But if she said she had eyes back there, I had no doubt that it was true. I ignored the note. I’m sure that annoyed both the girl and the boy, but it also very likely saved me from the unspeakable throttling I would have gotten if Sister happened to be looking my way – or directly the other way.

* * * * *

Catholic school was a place where behavior was paramount. What you did and said, and even what you thought, could land you in big trouble – in this world, as well as in the next. The list of infractions was long, and somewhere near the top was the sin of swearing.

I have no memory of my classmates uttering a curse word. It was as though the tongue that formed the blessed prayers in Latin every weekday morning, confessed its transgressions on Saturday, and received Holy Communion on Sunday was incapable of sharing its place or function with profane language.

And then there was my aunt, an enormous woman who struck fear in our hearts, but who also brought us delicious pastries and cookies from the Italian bakery. She would sit at the kitchen table and tell stories about her life, punctuating every point with a string of words I wouldn’t dare repeat, even to myself. Sometimes she’d stop, glance over at me, and say, “Pardon my French.” This was more shocking than the actual swearing. I had heard people speaking French before, but had no idea there was any connection. When I entered junior high school and the guidance counselor asked me if I wanted to take French, I was still worried about my immortal soul, and said no, without hesitation.

* * * * *

On countless occasions, my mother felt the need to explain why she couldn’t help me untie the knots in my shoelaces – as I’d requested – at the exact moment she was putting away the groceries. Or why she was unable to adjust the vertical hold on the television for me while she hemmed a dress or fed the cat.

“I only have two hands,” she would say.

Again, I didn’t understand why that was a problem. Two hands seemed to be the limit for every person I had ever met. The octopus in my coloring book had eight, but there was a lot to do, even in the ocean. Maybe you could never have enough hands.

* * * * *

Once, I told my father that I couldn’t find my baseball glove. He asked me where it was the last time I saw it. This was an impossible question to answer. That was the very thing I didn’t know – where it was. If I knew where it was, it wouldn’t be lost. I had to conclude that I would likely never see my baseball glove again. And then my father said another one of those things that I hadn’t considered, but that would, from then on, subtly haunt the edges of my mind.

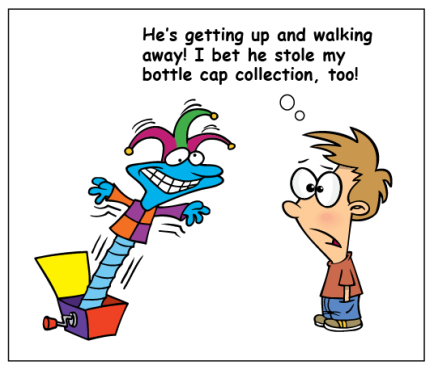

“Your glove didn’t just get up and walk away.”

“I know,” I said. But I didn’t know. I couldn’t recall ever seeing inanimate objects walking around, but things did disappear a lot, especially from my room. Armed with this new suspicion, I developed a technique for anticipating motion and then turning quickly, hoping to catch a favorite comic book sliding itself under a dresser, or fully expecting to spot my Slinky sneaking down the stairs toward the front door. I’d often attempt to get my mother to locate the missing item for me, but she was usually busy sewing curtains or sweeping the floor, and only had two hands. And while it might have helped if I’d had eyes in the back of my head, I had apparently inherited that deficiency, too. There was a single incident when, in exasperation, I tried speaking French. That didn’t work out so well either.

kalabalu

August 31, 2013

Hilarious 🙂 well done 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 1, 2013

Thank you. I’m glad you liked it.

LikeLike

kalabalu

September 1, 2013

All the best for future post 🙂

LikeLike

mizzpaw

August 31, 2013

I love your writing! Sharp, right on, hilarious!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 1, 2013

Thank you, mizzpaw. I look forward to reading your blog very soon.

LikeLike

Anonymous

August 31, 2013

My husband had a saying that our kids will surely remember: “I know you better than you know you.”

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 1, 2013

I had a teacher who said something similar: “I know what you’re thinking before you do.” Or something like that.

LikeLike

bitchontheblog

August 31, 2013

Oh, Charles. There I was, poised to shed a tear when you popped up. Now I am laughing.

My mother too had only two hands. I have four. As to eyes in the back of your head. It’s true. Mothers (hair colour immaterial) do have eyes in the back of their heads. Which is reassuring. A health and safety requirement. Whereas one’s father claiming to be all seeing is a catastrophe. And we weren’t even Catholic. No nun in sight. I remember the moment that belief and his authority toppled from its pedestal: My boyfriend, stoned out of his head, had a long conversation with my father and said father (a guy you can’t pull wool over his head) missed the signs. Oh, did I snigger. Silently. So much for investigative journalism.

As to your French, and where it all went wrong: Do not worry. The deadly delicious J (friend of my equally delicious son) told me that his French stretches to max three words, vital to get him what he wants in the South of France. Make that four: Merci.

U

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 2, 2013

Ursula, isn’t it possible that men also have the extra pair of eyes, but we just take more naps than women do? (I don’t know your father, but feel the need to come to his defense. I’m not sure why.)

LikeLike

Akshita

August 31, 2013

This was downright hilarious! Terrific post! 😀

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 2, 2013

Thank you for taking the time, Akshita. I appreciate the kind words.

LikeLike

reinventionofmama

August 31, 2013

I loved this! Mostly because I say the same silly things to my girls.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 2, 2013

It’s funny how, as parents, we say the very things to our kids we swore we’d never say.

LikeLike

subodai213

August 31, 2013

Oh, yes….that was my experience, too.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 2, 2013

You mean they said these things in Detroit, too?

LikeLike

mariceljimenez

August 31, 2013

Too funny! Somehow I’ve managed to, not grow them, but somehow make my eyes do a 360 and turn all the way around. Unfortunately my catholic school upbringing did NOT hold back the cursing. That’s probably why God refuses to give me 8 arms… something I pray for daily.

I wonder if my kids are just as confused… I keep reminding them I’m not an Octopus.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 2, 2013

Your comment made me think harder about what it might be like to have eyes back there. I’ve been in cars that have video cameras pointed toward the back, with a monitor that shows the driver what’s behind the car. It’s very confusing.

LikeLike

cat

August 31, 2013

Another superb write, Mr. Bronxboy55 🙂 … another gold star for you … thank you for making me smile today … Love, cat. (http://catsruledogsdroole.blogspot.com/)

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 3, 2013

Thanks for the gold star, cat. You always have something nice to say.

LikeLike

susielindau

August 31, 2013

I remember being very literal in translating adults, but I was pretty young. Today’s kids seem so much more sophisticated.

I could picture your Aunt and am Jonesing for those pastries!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 3, 2013

I have a feeling you live closer than I do to anything like those pastries, Susie.

LikeLike

rangewriter

August 31, 2013

It’s a wonder you never got diagnosed with Tourette’s syndrome, as you herked and jerked your head trying to keep track of your slinkies and your comic books. Another delightful look back at the peculiarities of childhood. Or would that be of adults?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 3, 2013

It’s all one big peculiar life, isn’t it, Linda?

LikeLike

Andrew

August 31, 2013

My mother couldn’t read minds. She would tell me, “What do you want? I can’t read minds.” Which is likely a good thing. There are some thoughts I wouldn’t want my mother to read.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 3, 2013

My mother said something similar, Andrew. Sometimes I wonder how many of these expressions our parents used, and how they got passed around from family to family.

LikeLike

nerdinthebrain

August 31, 2013

My mom used to inform me of a couple of things: she wasn’t Wonder Woman and she wasn’t made of money. I found these things to be obvious, but she wanted to tell me pretty often anyway. 😉 Thanks for sharing another great post!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 3, 2013

Yes, the “made of money” phrase always stopped me in my tracks. I’d immediately wonder if there were people out there who were made of money. And now that I think about it, I believe there are.

LikeLike

Kate

August 31, 2013

Love this! Definitely going to share this with my class when we talk about figurative language and euphemisms! Excellent!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 3, 2013

Thanks, Katie. I think our parents used that figurative language in order to get their message across, quickly and clearly. It’s amazing how often that failed to work with me.

LikeLike

greenroomgallery

August 31, 2013

I will no doubt spend my Sunday having random reminders of the ‘literal confusion’ I struggled with then, still does and what I myself has passed on to my unsuspecting offspring. Thanks for mostly brightening up my morning 🙂 Love your art!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 3, 2013

Thanks, Charlotte. I hope you’re doing well.

By the way, the original art for most of the cartoons on my blog were drawn by Ron Leishman: http://www.toonclipart.com.

LikeLike

Alex Rodrigue

August 31, 2013

It’s a very basic grammatical rule of the French language to apologize in English after each sentence uttered.

Bonjour Monsieur, pardon my french. Comment allez-vous, pardon my french?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 3, 2013

I don’t know. Something tells me she wasn’t really speaking French.

LikeLike

Alex Rodrigue

September 3, 2013

Are you sure? I sure didn’t quite understand that.

LikeLike

Damyanti

August 31, 2013

I don’t know about eyes on the back of your head, but the inside of your head must be a wonderful place, both as a child, and now.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 3, 2013

Have you ever wondered what it would be like to visit another person’s mind, even for a few minutes? I don’t think we could handle it.

LikeLike

Thoughtsfromthesummerhouse

August 31, 2013

A couple of days ago I wrote in my blog about paranoia, your BRILLIANT post took me back to my childhood and now I know where my inclination to be constantly looking over my shoulder comes from. Whenever I went out to play my mum would say ‘Don’t do anything naughty, I’ll be watching you’…….!!!!!!!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 3, 2013

It’s scary enough to have your mother watching. We also had the nuns, Jesus, Mary, all the saints, and Satan, too. Quite an audience.

LikeLike

nickyab

August 31, 2013

Excellent post! lol I quote ‘ Once, I told my father that I couldn’t find my baseball glove. He asked me where it was the last time I saw it. This was an impossible question to answer. That was the very thing I didn’t know – where it was. If I knew where it was, it wouldn’t be lost.’ This is what my hubby says to me at times even though I’ve told him not to..for obvious reason!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 3, 2013

It can be an exasperating question, but it can also be helpful. Sometimes retracing our steps triggers a memory that lets us switch tracks, and suddenly remember the missing action. But I never did find that baseball glove.

LikeLike

Chichina

August 31, 2013

I`m still trying to figure out how tall I was when I was

knee high to a grasshopper.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 4, 2013

I guess it would depend on the grasshopper, but probably pretty short.

LikeLike

earthriderjudyberman

August 31, 2013

A very humorous post, Charles, and one I can relate to. I was convinced my Mom did have eyes in the back of her head. Just HOW did she know what I did or was about to do? Spooky.

This week, I told one of my classes that I had eyes in the back of my head. My comment did follow someone doing something they shouldn’t. But I think they’re on to me. 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 4, 2013

It takes only one sly move on your part to get them wondering, Judy. But I’m sure you figured that out a long time ago.

LikeLike

morristownmemos by Ronnie Hammer

September 1, 2013

What a delightful post, Charles. How do you remember all those things that grown ups said?

When my mother was waiting for me, if I answered, “I’m coming” she always responded “So is Christmas!”

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 4, 2013

My mother said that, too, Ronnie. There must have been a handbook they all studied from while they were raising us.

LikeLike

climbing bean

September 1, 2013

I caught myself saying to my children, ‘If I see you do that again…’ and then realised it implied that they were free to do it, just as long as I didn’t see them!

Great post.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 4, 2013

That’s how I probably would have interpreted it, too: as a suggestion that I learn to be sneakier.

LikeLike

hemadamani

September 1, 2013

I look forward to your post and once again, it has left me laughing and thinking, ” I say that too” . I love the way you portray the mundane childhood memories so brilliantly. 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 4, 2013

Thank you, Hema. I always like knowing that we’ve discovered another common experience from childhood.

LikeLike

Robin

September 1, 2013

Very funny post. I think my parents favorite was “money doesn’t grow on trees!”. My son is very literal, and we were told to work with him on idioms because he really doesn’t get them at all. For instance, when I ask him to “crack the window” in the car, he is totally perplexed; or when I want to “give him a hand” with something. Every time I catch myself saying one, I now know to explain it…. We borrowed a dictionary of idioms from the library this past spring, with the the history behind all these sayings and had a good laugh as we heard all about where they originated.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 4, 2013

I wish my parents had thought to elaborate a little, Robin. It would have saved me years of pointless wondering.

LikeLike

Philster999

September 1, 2013

Merde! C’est un blog merveilleux.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 4, 2013

Give me a break, Phil. You know the only French I’m familiar with is on the back of cereal boxes. Source de 6 elements nutritifs essentiels!

(Okay, I copied that.)

LikeLike

vgfoster

September 1, 2013

Great post! I used to tell my daughter that both of my hands are busy right now, you’ll have to figure out how to do it yourself or wait until I’m finished. She figured a lot of things out on her own that way.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 4, 2013

That sounds like a much better approach, Vanessa. Thanks for the comment.

LikeLike

jeanjames26

September 1, 2013

I once sensed my little guy doing something behind my back and called him on it, and I overheard him say, “How did you know that?”, when my older son responded, “Mom has eyes in the back of her head she knows everything!” Well, not everything, but I do know with the eyes in front of my head what a great post this was!!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 5, 2013

You’ve taken the parents’ shorthand one stop further, Jean: you have your kids doing it for you. That’s brilliant.

LikeLike

zeuz3000

September 1, 2013

hehe!! awesome post…

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 5, 2013

Thanks, William. And I like your poetry.

LikeLike

John

September 1, 2013

Once again brilliant, funny and oh so true.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 5, 2013

Thank you, John. By the way, I thought your latest post was great:

LikeLike

kasturika

September 1, 2013

🙂 The teachers in our school had eyes behind their heads alright. But there was something wrong with their ears – must have traded an extra pair of eyes for an ear. They told us that they had two ears but one was of no use as they could hear only one student at a time. We never figured out which of the ears was defective…

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 5, 2013

I’d never heard of that saying, but it makes sense. I find that if two people are talking, I can’t really understand what either one is saying.

LikeLike

Hippie Cahier

September 1, 2013

I did not attend Catholic school, but I assume it would not have been wise to ask Sister if you had chosen the right shade of yellow for the canary you were coloring.

As always, a masterfully crafted piece!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 5, 2013

You assume correctly, Hippie. We were pretty much done with coloring after kindergarten. In school, anyway.

I’m glad to hear you had a good birthday.

LikeLike

Val

September 1, 2013

I missed reading your posts. Oh and hey – nuns don’t have eyes at the back of their head, they have periscopes.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 5, 2013

Funny you should say that, Val. Sometimes the teacher would be out in the hall talking to someone, but she could still see what was going on inside the classroom. At long last, you’ve given me the explanation.

LikeLike

reneejohnsonwrites

September 1, 2013

I love your recollections about Catholic School. Who knows what the nuns might have been hiding under those robes. An extra pair of eyes would be the easiest to believe.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 5, 2013

My older brother used to tell me that the principal had a machine gun under her habit. I believed it at least until the fourth grade.

LikeLike

sarahillariouslytwisted

September 2, 2013

This post made me travel back to my child hood when I had to listen the same things. Parents are all same.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 6, 2013

I agree. On some level, most parents are dealing with the same issues, and tend to say the same kinds of things.

LikeLike

Snoring Dog Studio

September 2, 2013

I’m convinced, and no one will convince me otherwise, that my two pairs of black eyeglasses walked off. After all, they each have two leg-like ear pieces. I just don’t understand why they’d decided to take that journey away from safety and sustenance.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 6, 2013

I think that’s why you’re supposed to wear only rose-colored glasses. They tend to love their life, and don’t go looking for something better. If they happen to show up here, I’ll let you know. Meanwhile, please tell me if you see my favorite gray T-shirt. It’s been gone for twenty-three years now, and I’m beginning to lose hope.

LikeLike

thomascmarshall

September 2, 2013

My aunt was a chain smoker and she had a gravelly deep voice that made it easy to find her in the dark as we sat outside during those family get togethers. I don’t remember any of them speaking French but I was more interested in my own world after all. I’d exchange the gravelly deep voice for some pastries, and also the bar tricks. My all time favourite dealt with turning the camel around on a pack of Camels without touching the pack. Great to know but eating a cannoli would have been better suited for my tastes.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 6, 2013

That’s a great image: finding your aunt in the dark. I hope you’re saving it for one of your stories.

LikeLike

Office Bird

September 3, 2013

Thank you for a great and very funny post! Ha ha – your boyhood self is right, these (very common) sayings actually are odd information! 😀

I look forward to check out more of your writing.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 6, 2013

Thanks, Office Bird. I hope you’ll stick around.

LikeLike

icedteawithlemon

September 3, 2013

Delightfully entertaining–as always. My sons knew I had eyes in the back of my head, although they frequently chose to risk the consequences anyway. I don’t remember ever telling my students that I had eyes back there, but I had them convinced that I could hear every word, sometimes before it was even muttered. If I had been a nun, I could have been wickedly good at it! (And only a single incident when you tried speaking French? I’m impressed.)

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 6, 2013

I’m sure you would have been an excellent nun, Karen. But your path allowed you to torment your students and your sons.

Hey, did I ever tell you that the nuns’ favorite team was the Cardinals? Well, a few of them liked the Angels, but most preferred Saint Louis.

LikeLike

icedteawithlemon

September 9, 2013

So, was their favorite football team the New Orleans Saints? 😉

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 10, 2013

My Catholic school career ended in June 1966. I don’t think the Saints were around until the following year. But if I had to guess, I’d say yes, that would have been their favorite team.

LikeLike

silkpurseproductions

September 4, 2013

You certainly have a way of bringing back childhood memories. I think all our parents and teachers (even the Nuns) had the same book of sayings to scare the crap out of us. Thanks for making me laugh today.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 6, 2013

Scare us or keep us guessing. Either way, it slowed us down.

LikeLike

Christiana Pilgrim

September 5, 2013

Wonderful and relatable, as always! When I read your title, I thought it was going to be a reaction to the news that Webster’s has allowed the slang definition of “literally” into their new dictionary, which confuses me no end. This was delightful, though, because I remember my mother telling me all these sorts of things. And, of course, when I did take French, the first thing my friends and I did was look up all the English swearwords in the dictionary so we could say them at home and explain we were practicing for class.

As to the eyes thing, I was floored when I started teaching and saw a film that explained that nuns would have the picture of the pope on the board just so, such that its glass would reflect the classroom. My mind was blown by the simple brilliance.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 6, 2013

Our classroom had a framed picture of the Pope on one side and another of our Monsignor on the other. The two reflections probably created a hologram of the entire class. It was hard to get away with anything, although I guess it didn’t help that we weren’t that smart.

Thanks for the great comment, Christiana.

LikeLike

Elizabeth Sharrod

September 6, 2013

I used to try and whiz my head round to see if things were walking but I blame Toy Story for that! I did see a monster with eyes in the back of its head… it was on Angel! I must admit, even though I know it isn’t real, it really did freak me out!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 6, 2013

Toy Story just confirmed what every kid already knew.

Thanks for the comment.

LikeLike

lostnchina

September 8, 2013

I’m convinced that my mother had not only eyes at the back of her head, but an extra set of ears and a nose that was out of this world. Her school friends used to call her Nosey. She could walk into a room, sniff around and say, “Something going on in here that I should know about?” – and we weren’t even smoking, or anything, just goofing off. But in later years we realized that eight times out of ten *something* was going on, the odds were in her favor. Maybe this was the case of your mother, Charles. Thanks for another trip down memory lane.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 9, 2013

Susan, there’s no doubt that the phrase extra-sensory perception came from motherhood, not the supernatural.

LikeLike

Lorraine Gouland

September 9, 2013

Great post. Glad your parents didn’t explain and left you wondering …

When I complained that I couldn’t find something, my mother would always say, ‘look with your eyes and not your mouth.’

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 9, 2013

That’s a great line, Lorraine. I’m surprised my mother never said it.

LikeLike

Lorraine Gouland

September 9, 2013

I give you permission to confound small children everywhere with it

LikeLike

chocolatecakeandheels

September 15, 2013

Great! Keep up the good work. ^_^

LikeLike

chocolatecakeandheels

September 15, 2013

Reblogged this on malaikalazar6.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 3, 2013

Thank you for both the comment and the re-blog. I appreciate your feedback.

LikeLike

aunaqui

October 14, 2013

“I developed a technique for anticipating motion and then turning quickly.”

I love it! I see it, I get it. I’ve missed your writing, friend! It is always so relatable and effortless to read. Really enjoyed this post!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 17, 2013

How did I overlook this comment? Sorry! I’ve missed your writing, too!

LikeLike

Choosing

December 13, 2013

I guess I am also guilty of using that kind of phrases with my children. They are getting used to them though. A few days ago, when I said something like “oh, this is really great!” in an annoyed voice about some kind of traffic situation, my younger son (5), stopped munching his cookie for a moment and then said “You are being ironic, mum, aren’t you?” 😉

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 17, 2013

Don’t you wish you could record your children when they say things like that? Hard to do when you’re driving, though.

LikeLike