Here’s the whole story about Willie Mays. But be prepared, because it’s a tale filled with drama and suspense. Okay, no it isn’t. Actually, it’s filled with stupidity and hurt feelings. And a sense of relief that caller-ID wasn’t yet available.

Here’s the whole story about Willie Mays. But be prepared, because it’s a tale filled with drama and suspense. Okay, no it isn’t. Actually, it’s filled with stupidity and hurt feelings. And a sense of relief that caller-ID wasn’t yet available.

Willie was a baseball player, if you didn’t know. One of the greatest, in a game that tosses that word around in much the same way it shovels money into the pockets of owners, agents, and third-basemen. He started his career in New York in 1951, and ended it there twenty-two years later. In between was a fifteen-year detour out to Candlestick Park in San Francisco, but we can pretty much ignore that part. His nickname, from his earliest days in the majors, was the Say Hey Kid.

My favorite player was Mickey Mantle, outfielder for the New York Yankees. Willie and Mickey had begun their careers at the same time and at about the same age. But by the mid-1960s, Mickey was in a steady decline, while Willie was still at the top of his game. Like a fool, I got into frequent debates about who was the better player. Somewhere in my mind, I knew the truth. Plagued by injuries and dragged down by heavy drinking, Mickey retired before the decade was out.

In 1972, the Mets finished third in their division. But the big story was that, through a surprise trade with the Giants, Willie Mays was returning to New York, and joining the team. Now approaching the end of his career, he was there to boost attendance, which would help the Mets see more revenue and allow Willie to play in front of bigger crowds at home games. He’d already hit 646 home runs, and would add fourteen more before he was through – and this long before anyone had figured out how to inject muscle power directly into the arteries. He deserved the attention.

Retiring after the 1973 season, Willie kept his New York residence and stayed with the team as a hitting instructor. He also continued to strive for a balance between his status as a baseball legend and his strong desire for personal privacy. I’d gone to a few games while he was with the Mets, but I can’t say we’d really crossed paths.

Until 1976.

I was a twenty-year-old, still in college, and working as a volunteer for the Leukemia Society of America. One of our activities was an annual marathon softball game. Held at a Little League field, it began at seven o’clock in the morning and ran until ten at night. In order to participate, we had to get people to sponsor us, pledging a specific amount for every inning played. We also accepted flat donations from spectators. As one of the organizers, I wondered: wouldn’t a celebrity attract more people, and more money? It seemed to work for car dealerships.

“I have the unlisted number for Willie Mays.”

I wasn’t sure I’d heard her correctly, but then she said it again. My sister-in-law worked for the phone company. She was offering to help me contact somebody guaranteed to pack the bleachers with celebrity-mad potential donors! I also considered what it would mean to be able to say I was the one who got Willie Mays to come to our little game. That wasn’t what mattered, obviously. But still.

“You’d give me his number?” I asked. This is the beginning of the stupidity part. She said she would, as long as I didn’t tell anyone where I’d gotten it.

I looked at the piece of paper and realized it was a combination of his uniform number, with the digits just repeated. What a coincidence, I thought. Later that afternoon, I slipped away from the family, went into my parents’ bedroom, and quietly closed the door. After, nine or ten false starts, I dialed the number and waited. It rang a few times. Then I heard his voice.

“Hello?”

It was Willie Mays. For some reason, I was surprised that when he answered the telephone, he said hello. That was how I answered the phone, too! We already seemed to have a lot in common.

I started to speak. “Mr. Mays…” That was weird, I knew, but to address him as “Willie” so early in our friendship would have been presumptuous. “I’m calling because I was wondering if you might consider appearing at a marathon softball game for the Leuk…”

“How did you get this number?” He sounded unhappy to hear from me.

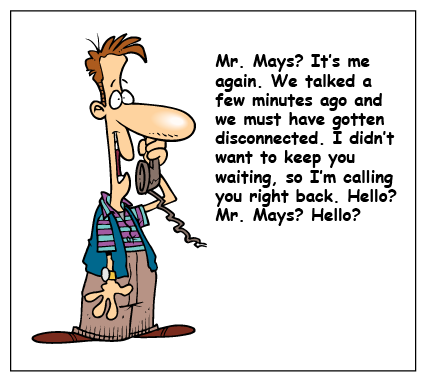

With my brain doing cartwheels inside my skull, I began to explain that someone I knew worked for the telephone company, and then tried to switch over to my pitch about raising money for leukemia research. He wasn’t interested. He said he’d find out who gave me his unlisted number and have that person fired. Then he hung up. I hung up, too, but only after fifteen seconds of stunned silence.

“What a jerk,” I thought. But I couldn’t decide if the jerk was him or me. Looking back, I now realize that I had invaded his privacy, just as telemarketers disrupt mine on a daily basis. I didn’t know – and never considered – what might have been going on in his life at the moment I called. Maybe he wasn’t feeling well, or was in the middle of an argument with his wife. Maybe he’d just received some bad news, or had smashed his knee against the coffee table as he reached for the phone. All I knew was that Willie Mays had hung up on me, and that he probably wasn’t coming to the softball game. And that my sister-in-law might lose her job.

A couple of weeks later, I sent a letter to the Mets, asking that they forward it to one of their newest players. His name was Mickey. He’d been traded earlier that season, and he, too, was nearing the end of his career. Mickey Lolich had been an excellent pitcher for the Detroit Tigers. He’d even hit a home run in the 1968 World Series – an unusual accomplishment for a pitcher, and something Willie had never done. He answered my letter, and said that he’d try to come.

At the end of September, on a cloudy Saturday evening, a big man in a leather jacket rode his motorcycle to a small field in Congers, New York. He played a couple of innings, signed autographs, then rode back off into the night. It was a memorable thing to stand at home plate, holding a bat and facing a major league pitcher. I even managed to hit a home run off Mickey Lolich. True, he was throwing underhand, and he was dressed in street clothes and boots. And the fences were at Little League dimensions. But it was still a fine ending to a story that had begun with stupidity and hurt feelings. I’d had enough drama and suspense to last me for a while.

And say hey, one more thing: Nobody got fired.

* * * * *

Willie Mays was such an incredible fielder that he once made a play in the 1954 World Series that is still known simply as The Catch.

ankushmehta

August 15, 2013

Reblogged this on Icanbeatit.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 16, 2013

I’m glad you liked it.

LikeLike

ankushmehta

August 16, 2013

🙂 🙂

LikeLike

Hippie Cahier

August 15, 2013

Well, your heart was in the right place. It was just attached to a 20-year old brain.

Another grand-slam post!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 16, 2013

Thanks, Hippie. I hope my brain has matured since then, but sometimes I’m not so sure.

LikeLike

White Pearl

August 15, 2013

Lol this was such a nice funny story 😛 Love your sense of humor 😉

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 16, 2013

I appreciate the kind words, White Pearl. And see? Your comment arrived here without a problem.

LikeLike

White Pearl

August 16, 2013

Yes I am glad it arrived 🙂 Thank you !

LikeLike

Elyse

August 15, 2013

What a great story. I’m assuming your sister-in-law now works for Booz Allen?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 16, 2013

I think she’s retired. But she did stay with the phone company for a quite a few more years. Almost everyone there knew the unlisted number, so they would have had to fire everyone.

LikeLike

Stacie Chadwick

August 15, 2013

It’s funny how a negative can be turned into a positive. I love that about life. I also love that you got to speak with Willie Mays, however brief and you know, slightly hostile.

Great post as always. =)

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 16, 2013

Stacie, I had no way of understanding how he felt at the time. I was focused only on how I felt. It must have been frustrating for him to go through all the trouble of trying to maintain some level of privacy, and then have people barging in anyway.

LikeLike

cecilia

August 15, 2013

God darling. I am so sorry but none of this meant anything to me. How very naughty of your sister in law. And how very delightful for you to be able to find another Mickey. Um. Are those the right things to say. I don’t know terribly much about rounders, I mean baseball. It is baseball isn’t it? Where you hit somebody at a run. Hit a run? What does that mean anyway to Hit the Run. Is it a man. Is there a man called the Runs, I mean The Run? And you hit him? That hardly sounds fair. Just not cricket really. Maybe Micky 1 thought you were going to make him The Run Man. Well i am off into the garden to roust out a naughty pig. I will smack her fat bottom as she runs.. Just for you..c

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 17, 2013

You sound exactly like I did when I tried to learn about cricket. It seems to make no sense, doesn’t it? And after your comment, I’m not sure I understand baseball anymore, either.

I hope you go easy on that pig.

LikeLike

icedteawithlemon

August 15, 2013

Great story! And congrats on the home run–even if it was off an underhand pitch and landed on the other side of a Little League fence.

As you know, most of my Major League baseball knowledge is limited to the accomplishments of St. Louis Cardinals, so I Googled Mickey Lolich and found this Wikipedia entry of particular interest: “[Lolich] is best known for his performance in the 1968 World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals when he won three games, including a victory over Bob Gibson in the climactic Game 7.”

So, in other words, you hit a home run off a pitcher who out-pitched THE Bob Gibson, ONE OF THE GREATEST PITCHERS OF ALL TIME. Way to go, Mr. Gulotta, way to go.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 17, 2013

Thanks, Karen. I’d never thought of it that way, but I guess you’re right. I have a feeling Gibson would have been slightly more competitive. He probably would have brushed me back a few times — maybe even plunked one off my head, just to send a message.

By the way, out of respect for your feelings, I didn’t mention that the Tigers had beaten the Cardinals in ’68. It was very big of you to bring it up yourself.

LikeLike

Experienced Tutors

August 15, 2013

You caught me again with a baseball story. I watched the video so does that qualify me for knowing something about baseball? A few more like this and I’ll be telling you about Babe Ruth – he was a famous baseball player by the way, that’s before you ask! 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 17, 2013

I’ll try to leave baseball out of future posts — at least for a while.

LikeLike

Experienced Tutors

August 19, 2013

No. Go ahead. See it as a mission to take civilisation across the pond. . .

LikeLike

Rick@RomanticHusbands.com

August 15, 2013

Thank you for sharing. You brought back so many fine memories. I too was a Mickey Mantle fan. It wasn’t easy rooting for a Yankee growing up in the shadows of Ebbets Field, (not literally). I too spent many dog days of summer debating the virtues of Mick the Quick and the Say Hey Kid. Of course, back in the days before Google, everything was a debate. Now you just pull out your phone and find the right answer in seconds…

Now…don’t get me started on Joe Pepitone.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 17, 2013

Do you remember the big deal it became when the media found out Pepitone was using a hair dryer in the locker room? It was a huge story.

LikeLike

Rick@RomanticHusbands.com

August 17, 2013

I do remember that story. Joe Pepitone was competing with another flamboyant Joe, Joe Namath. It was a transitional period in sports and how we perceived players. I’m not sure if it was the players who were changing or the media coverage. Gone was the quiet dignity and respect for the players of the 40’s and 50’s.

LikeLike

Patti Kuche

August 15, 2013

So Mickey Mantle had a vanity telephone number! I am sorry for your discomfort Charles, but this story goes in so many wonderfully slapstick directions!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 17, 2013

No, Willie Mays had the vanity telephone number. I doubt players today would do the same, because it would take a computer about twelve seconds to figure out the correct combination.

Thanks for the comment, Patti.

LikeLike

Betty Londergan

August 15, 2013

I love this story SO much — and just because you shared, I have to, too. In November 1979, I was moving out to San Francisco from Denver and was scared to death to go to the big agencies to look for a job. I was interviewing at an agency by the wharves, and had 1/2 hour to kill, so I went in to a little cove bar by the agency with my big portfolio and asked the bartender for a Coke. The elegant, silver-haired gentleman a few stools down asked me about my interview, talked to me a little bit about jobs and life, wished me luck, and offered to buy my soda. I was going to refuse when the bartender looked at me and said, “You know that’s Joe DiMaggio buying you a drink, right?” So … yeah. It was. And then he invited me to his 65th birthday party — which of course I didn’t go to because my broke-ass artist boyfriend was coming in and I had to pick him up at the airport. Ahhhh, youth! Loved this post!!!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 17, 2013

Your story tops mine, Betty. It’s not even close. But what do you think he was up to, inviting you to his party — that sixty-five-year-old baseball immortal and part-time coffee maker spokesperson?

LikeLike

marymtf

August 16, 2013

Nice one, Charles. But then your stories always have layers to them. It’s not primarily about baseball, is it? 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 17, 2013

No, of course not, Mary.

But what is it about?

LikeLike

marymtf

August 17, 2013

You know, Charles, that once you send your children out into the world you’re no longer in control of your words or how people interpret them. I’m thinking how sweet it is to remember a time when you and your world were so innocent. It’s an essence that should be bottled and cracked open now and again when you’re wanting to revist that foreign country.

That’s the best you’ll get out of me at the crack of dawn. I’m sitting in the computer room of a youth hostel and some young thing downstairs is serenading us all with Bob Dylan’s Knockin on Heaven’s Door. Being the only other person properly awake I think I’m the only one appreciating it.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 19, 2013

The trick, I think, is to write about something specific and detailed, but in a way that’s general enough to remind people of their own experiences.

It’s always good to hear from you, no matter what time it may be.

LikeLike

marymtf

August 19, 2013

Thanks for your kind words, Charles, you’re always kind.

You do ‘specific and detailed, but … general enough to remind people of their own experiences’ really well.. Not everyone can. I haven’t any specific memory of my own, just a bunch of blurred ones I’d rather not remember. What touched me about yours was that your younger self hadn’t understood about consequences, of accessing a private phone number. Nor had you understood (back then) that someone with a public persona can also be a private person. This is where I’m tempted to say, ah, youth, but I won’t.

That young man sitting in a stairwell only understood it was the best place other than the shower to showcase his voice. He didn’t understand the catcalls coming from the various rooms. Perhaps he’ll write a song about it one day.

LikeLike

Phone Insurance Australia

August 16, 2013

Well…. glad nobody got fired.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 19, 2013

I doubt I would have told the story if it had turned out that way.

LikeLike

Philster999

August 16, 2013

I always love your unique combination of understatement and pathos: “It was Willie Mays. For some reason, I was surprised that when he answered the telephone, he said hello. That was how I answered the phone, too! We already seemed to have a lot in common.”

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 19, 2013

Actually, Phil, I was surprised that he answered the phone at all. I don’t know why, but I’ve always assumed the rich and famous have people to perform those menial tasks for them.

Are you back?

LikeLike

Arindam

August 16, 2013

Sir Charles, I have to confess, I have no knowledge about Mickey Mantle and Mickey Lolich. And all this happened with you, much before I was born. My ignorance could not stop me from enjoying this post.

The story was very engaging and interesting. I always enjoy stories those end with a happy note; after all happiness is something we search at the end of everything.

I just wonder, if your sister in law ever dared to give you number of another person while she continued with her job. 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 19, 2013

Arindam, I would have been shocked if you’d have ever heard of either of those two ballplayers. You’re too separated from them by time and distance. But I’m glad you could still get something out of the story. My sister-in-law never offered to reveal anyone else’s telephone number. I guess we both learned a lesson.

LikeLike

Snoring Dog Studio

August 16, 2013

What a wonderful tale. I am so surprised you got up the nerve to call Mr. Mays! What an awful couple of minutes that had to be. Your intentions were good. Just remember that. There’s a wonderful lesson in here, too – sometimes reaching for the stars isn’t a good thing – you can make a difference by opting for the smaller gesture.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 19, 2013

It was just too tempting, Jean. The very possibility.

LikeLike

Sarah

August 16, 2013

I never knew of this brush with greatness, Charles. Or should I say these two brushes (i.e., Willie and Mickey). See, the reason your life has gone the way it has is so that you have plenty to write about in your blog! Thanks for another great post, with myriad layers and lessons (as per your usual).

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 16, 2013

Not exactly a brush with greatness, Sarah. More like a brush-off. But Lolich definitely came through. He seemed like a nice guy.

LikeLike

Wyrd Smythe

August 16, 2013

Dude, that was a great story!!

I’m sure you take heart in that there was just no way that phone call was going to go your way. I do love the image… you should have called him back! 🙂

(I’m starting to feel one of my greater regrets is not having been a serious baseball fan until well into adulthood. I’m envious of those who grew up following it!)

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 16, 2013

You know what I think? Because you didn’t grow up with baseball, you get to experience it with all the enthusiasm of a little kid — but through the eyes and with the experience of an adult. I envy that. I’ve become somewhat disillusioned by what the sport has become.

LikeLike

Wyrd Smythe

August 16, 2013

Ha! Good point… Once again we see that, yes, the grass does seem greener on the other side of the fence!

LikeLike

cat

August 16, 2013

Have to admit, I did not get it … base ball, ok, explain the rules to me … foot ball, explain … soccer, ya … still, love your writings a lot, Mr. Bronxboy55 … Always, cat.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 22, 2013

I understand completely, cat. I used to watch curling because it’s pretty big in Canada, as you know. The basics were pretty clear, but the scoring remains a mystery. Also, the sweeping part.

LikeLike

subodai213

August 16, 2013

I’m not a baseball fan, but it was hard not knowing something about it. My mother was a diehard Tigers fan, and both my brothers played semi pro. I grew up in Detroit. Mickey Lolich (and Denny McClain) were the pivotal players in beating the Cardinals in the 1968 World Series. The Cards didn’t give it away, either…both teams played HARD. It was a Very Big Deal in Detroit AND in Michigan. And from what I remember, Lolich was that kind of guy…someone who’d show up at a Little League game and sign autographs, not because he was conceited, but because..well, little boys have heroes.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 22, 2013

I later learned that Lolich didn’t want to leave Detroit, and had little interest in going to New York. He was hurt when the Tigers traded him, which only makes his generous gesture all the more impressive.

LikeLike

earthriderjudyberman

August 16, 2013

I’m not so sure your encounter was isolated. I told you once about my run in with him when I was a reporter and assigned to cover him at the airport. I tried to be generous and write off his brusqueness to jet lag. Sure, he probably got inundated with requests for appearances, etc. But I still prefer warm and fuzzy.

Thank heavens for players like Mickey Lolich who know what a really BIG deal it is for kids – and the public – to see them up close and personal.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 22, 2013

Lolich was definitely a good guy, Judy. And maybe Willie is, too, and I just didn’t go about it the right way.

LikeLike

Bruce

August 17, 2013

Great catch and post Charles. I wonder if Willie Mays would remember your call? How good would it be if he read your post and called you? Perhaps he is warm and fuzzy as earthriderjudyberman prefers.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 22, 2013

I think it was a matter of limited time and a desire for privacy — competing with an almost endless stream of people who wanted something from him. I really should have tried the written letter approach first.

LikeLike

Terri S. Vanech

August 17, 2013

Can always count on you to make me smile. And now I’m thinking of all my many boneheaded moves over the years. Funny … I can’t always blame youth! 😉

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 22, 2013

I guess we have to blame it on our flawed humanity. That seems to last well beyond youth.

LikeLike

Terri S. Vanech

August 22, 2013

And some of us (ME!) have those flaws in spades!

LikeLike

Tom Marshall

August 17, 2013

I can hear the beginning of a story/play here. Guy calls famous person to help a charity. Famous person is really nuts/or fed up and begins stalking the guy to give him a taste of what it’s like. Showdown is the charity benefit. Reverse the roles and make it a comedy.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 22, 2013

Let’s add that to the list.

LikeLike

souldipper

August 17, 2013

Since you tagged him, Charles, bet this confession has been read by the Say Hey Kid. Watch it…he may sic one of his staff onto finding you so he can make amends. Bet you wouldn’t call it an invasion!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 22, 2013

I’m not holding my breath, Amy. He couldn’t possibly remember the incident.

LikeLike

shoreacres

August 18, 2013

The moment I most loved about this is the moment he picked up the phone and said “Hello”. I’ve had that experience twice in my life. In my case, I wasn’t using unlisted numbers, but I certainly expected layers upon layers of executive assistants to be my conversation partners. Instead, with nothing but pure chutzpah on my side, I called and made contact with a couple of people I really shouldn’t have been able to get to, but there they were, just answering their own phones.

It was a shock – as you say, who expects legends to be answering the phone? I suspect that kind of experience is nearly impossible today, what with smart phones, caller ID and such. But it surely was fun back then!

Of course, today we could just ask the NSA to pass on our messages for us. 😉

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 22, 2013

I once called a magazine to discuss postage costs to Canada, and the publisher — who was also a well-known author and speaker — answered the phone. Assuming they had the same huge staff, I expressed my surprise, and he said, “Actually, I’m the only one here right now.”

LikeLike

Chichina

August 19, 2013

Such a great story……. I loved everything about it……

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 22, 2013

It was a sort-of-happy ending, wasn’t it?

LikeLike

Chichina

August 22, 2013

It was indeed. You done good…… lol

LikeLike

reinventionofmama

August 20, 2013

I was hooked on this blog before I even read the article. Mostly Bright Ideas – what a great name!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 22, 2013

Thank you. I like your blog name, too. The mama part is hard enough — almost impossible, really. To add the process of reinvention to that is daunting. I hope you’re doing well.

LikeLike

reinventionofmama

August 22, 2013

It’s a process! If it gives me a chance to do something I love I am going to go for it. My little brother used to tell me “you only live once, go for it”. Wise for a kid. Maybe I’ll write about him today. Thanks for the comment.

LikeLike

silkpurseproductions

August 21, 2013

Great post! I imagine you had great fantasies of making that call and Willie showing up at your event and the two of you becoming BFFs. That’s how it would have been playing in my head. Then reality hits you square in the face and you realize people are just people and they can get caught off guard which can lead to them reacting harshly or rudely which may be out of character for them.

I like that the other guy was willing to help you out and, although I don’t have a clue who he is I’m sure he made more than one young lads day.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 22, 2013

I can certainly relate to Willie’s response much better today than I could when I was twenty.

By the way, I saw a tee-shirt yesterday that made me think of He Who. It said “I put ketchup on my ketchup.”

LikeLike

silkpurseproductions

August 22, 2013

That’s hysterical! He would love that.

LikeLike

Antonio Cruz

August 21, 2013

Great story and I loved the title.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 22, 2013

Thanks, Antonio. I appreciate the feedback.

LikeLike

happykidshappymom

August 22, 2013

Hi Charles, what a great story. This part here, that you saved for the end, “At the end of September, on a cloudy Saturday evening, a big man in a leather jacket rode his motorcycle to a small field in Congers, New York. He played a couple of innings, signed autographs, then rode back off into the night,” would make a fine opening to a book. So full of imagery, of questions, and perfectly concise.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 24, 2013

Thank you, Melissa. You’re one of my favorite bloggers — and writers — so that kind of feedback means a lot.

LikeLike

micagaleano13

August 24, 2013

Reblogueó esto en micagaleano14.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 24, 2013

Gracias.

LikeLike

ThePeopleIHaveSleptWith

September 11, 2013

good read! I enjoyed it, made me laugh!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

September 12, 2013

I’m glad. Thank you for saying so.

LikeLike

Nectarfizz

September 20, 2013

I sort of think you let him off a little easy. I mean, he was kinda rude. I don’t know many occasions where I would say “When I find out who gave you this number I will have them fired” You gave him the benefit of the doubt so..It’s cool. I still think that the conversation says more about your heart and it’s good places, than his, but then that’s cause I know and adore you. One thing to want privacy, another to threaten to have someone fired, but then, I am not hounded daily..still I am stubborn and refuse to think he couldn’t have been nicer. Since, my grandpa raised me to be nice even if I am totally ticked.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 3, 2013

My understanding attitude has come with age, Bekki. For years after the conversation, I couldn’t see the guy’s name or face without recalling that hurt feeling. As an adult, I can relate better to his reaction.

LikeLike