I waste too much of my brain engaged in trivial thoughts. I’m frequently tempted to call the toll-free numbers on the sides of food packages, just to see if anyone is really there. I struggle to remember what ever happened to those poor people stranded on Gilligan’s Island. Mostly, I wonder how extension cords manage to tie themselves up in knots.

I waste too much of my brain engaged in trivial thoughts. I’m frequently tempted to call the toll-free numbers on the sides of food packages, just to see if anyone is really there. I struggle to remember what ever happened to those poor people stranded on Gilligan’s Island. Mostly, I wonder how extension cords manage to tie themselves up in knots.

Every so often, though, I experience a fleeting moment of perspective. This tends to occur when I’ve turned my attention to the night sky, that dark expanse filled with planets, stars, galaxies, and too many inscrutable mysteries to count.

How big is the universe? How did it begin? Will it go on forever, or will it end someday – and if so, how? And is there anyone else out there, or are we alone?

These are the questions science and religion have been trying to answer for thousands of years. If we knew where we came from, maybe we could figure out why we’re here and where we’re going.

The astronomy books tell us that right before the Big Bang, everything in the entire universe was packed into a point much smaller than the period at the end of this sentence. What the books fail to mention is that it must have been smaller than the period at the end of almost any sentence. It’s just one more quirk of nature that all periods are roughly the same size.

I may dwell on the diameter of punctuation marks for a while, but I can stall for only so long, and then I’m forced to return to the bigger issue, which is the universe and its infinite compression. It doesn’t seem possible, does it? The universe being that small, I mean. If you told me South Dakota was once the size of an English muffin, I’d have a hard time believing it, or that Baltimore could have fit inside a plastic sandwich bag. I can barely imagine a toaster oven ever being that tiny. Yet, the theory states that everything that has ever existed was once crammed into something called a singularity, a dot too minute to measure. I think about this idea whenever I try to hang another coat in the closet, or squeeze a container of leftover mashed potatoes into the refrigerator, or close my underwear drawer. You can get just so much stuff into a given space, and that’s it.

How is it that such limits don’t apply on the largest of scales? The universe has a lot of really big things in it. Heavy things. There are black holes, for example, that are forty billion times as massive as the sun. The Milky Way has a hundred billion stars, many with huge planets orbiting them. There are more than a hundred billion galaxies that we can see, and a lot more dark matter that we can’t. I accept the fact that atoms are mostly empty space, but that doesn’t seem like enough of an explanation. I’ve seen cars that were flattened to the size of a coffee table, but that’s as little as they would get.

I wish I could find an astrophysicist who would sit down and explain this to me, and who wouldn’t be allowed to leave until I understood it. On the other hand, I also wouldn’t mind if he admitted that he doesn’t get it either. That might be even more satisfying.

I wish I could find an astrophysicist who would sit down and explain this to me, and who wouldn’t be allowed to leave until I understood it. On the other hand, I also wouldn’t mind if he admitted that he doesn’t get it either. That might be even more satisfying.

After the Big Bang, the universe expanded quickly. So quickly that scientists try to describe what was happening after a millionth of a second, and then a millionth of a second after that. I don’t really know how anyone can talk that fast, but then, I’m not a scientist.

The universe in its present state is gigantic in a way that is impossible to fathom. And it’s getting bigger. Our galaxy is a hundred thousand light-years across. That means that a beam of light, traveling at 186,000 miles per second, would take a thousand centuries to get from one end to the other. The nearest star to our sun is twenty-five trillion miles away.

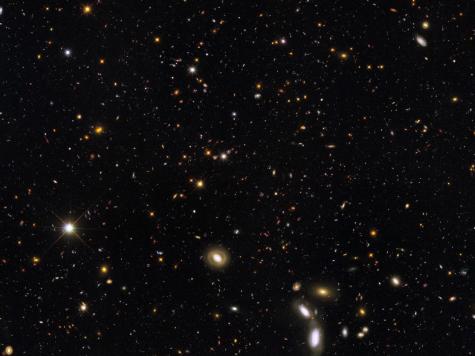

Here’s a photograph taken by the Hubble Space Telescope:

It shows a slice of the sky – a slice whose width is one-third the diameter of the full moon. That thin region contains more than seven thousand galaxies, many just like our own. If we could step back far enough, we would see clusters of galaxies, and clusters of clusters.

It shows a slice of the sky – a slice whose width is one-third the diameter of the full moon. That thin region contains more than seven thousand galaxies, many just like our own. If we could step back far enough, we would see clusters of galaxies, and clusters of clusters.

With that many stars and solar systems, some people believe the universe must be teeming with life. I think so, too, although I don’t care for the word teeming. It reminds me of a swamp filled with dragonflies and bullfrogs. I know astronomers would be thrilled to find dragonflies and bullfrogs on another planet, but I’m hoping for something with a little more aptitude for abstract conversation.

Here’s another Hubble picture, this one of the Horsehead Nebula:

Made mostly of hydrogen and dust, this object is about five light years tall – in other words, its height is greater than the distance from our sun to the nearest star. And it’s just a part of a much larger cloud. The Horsehead Nebula is fifteen hundred light years away, which means the photons that formed this image began their journey to Earth when Justinian the Great became Byzantine Emperor in 527 AD. I don’t know what was so great about Justinian, but I bet he never heard of the Horsehead Nebula. I also don’t understand why the universe needed to be so incomprehensibly enormous. It actually makes me angry sometimes, especially when I can’t find a place to park.

Made mostly of hydrogen and dust, this object is about five light years tall – in other words, its height is greater than the distance from our sun to the nearest star. And it’s just a part of a much larger cloud. The Horsehead Nebula is fifteen hundred light years away, which means the photons that formed this image began their journey to Earth when Justinian the Great became Byzantine Emperor in 527 AD. I don’t know what was so great about Justinian, but I bet he never heard of the Horsehead Nebula. I also don’t understand why the universe needed to be so incomprehensibly enormous. It actually makes me angry sometimes, especially when I can’t find a place to park.

Some mathematical models of the universe suggest there was a time when even empty space didn’t exist. Different theories say there’s no such thing as empty space. Others claim the universe is finite and has an edge, or that it’s infinite, and that if you could travel long enough in a straight line, you’d end up back where you started. Which is exactly what I seem to have done. I’m still curious: Has anyone ever called the toll-free number on the back of the Twizzlers package? And what did ever become of those seven stranded castaways? I spent the best years of my childhood caught up in their fate, and then missed the outcome. I was probably too busy staring at the night sky. Or, more likely, trying to untangle an extension cord.

Carol Deminski

July 14, 2013

The thing is… people also used to think the world was flat, but it turned out it wasn’t. People thought if you sailed past the line of the horizon, you’d fall off the edge of a cliff.

When you don’t know the world is round, it’s a logical thought, right? Past “over there” I can’t see, and normally when that happens there’s a cliff, therefore there’s a cliff over there.

The mind cannot comprehend a lot of things, and infinity is definitely among them.

I remember the first time I saw the Grand Canyon, and I was awestruck. In fact, I was so awestruck I almost felt like crying (I’ve heard many people weep when they see the Canyon for the first time, actually.) This is because the mind cannot comprehend the Grand Canyon. It’s too large, too deep, and too vast to comprehend. In fact, most times when you look at the Canyon, it looks FLAT! That’s because the eye does not have sufficient ways to process the depth perception.

Okay, speaking of the eyes, there is a blind spot in your eye… it occurs naturally. I believe it’s where the optical nerve is attached, but I’m not a doctor, I don’t remember. But the senses of a human being are limited, and we just have to accept that. We can’t see X-rays, or Gamma Rays, or the InfraRed spectrum, but it doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist.

Similarly, we cannot possibly imagine the infinite time that elapses at the edge of a black hole. We can’t imagine how we’d be squeezed into nano-molecules (a word I just created, I think) because of the pressure inside a black hole.

BUT… for those super-genius astro-physicists with a lot of math at their disposal, another language I don’t speak too well at all, they can try to show how the universe was likely a singularity, and the big bang and lots of other stuff that the human mind goes… huh? at when you don’t have the complicated spaghetti math they do up those ivory towers of theirs.

Still, it’s fun to think about these things, without the benefit of the math. Preferrably while eating Twizzlers and watching old episodes of Gilligan’s Island on TV….

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 15, 2013

Thanks for the thoughtful comment, Carol. Part of the problem is that we tend to assess everything through the filter of our own limited, human experience. Science tosses around huge numbers when discussing time and distance, but we have no context for those figures, and I think eventually the mind just bails out. Religion does the same thing when it describes a God who is everywhere, and who always was and always will be. It’s all incomprehensible.

LikeLike

Carol Deminski

July 15, 2013

Yep, there’s the rub.

LikeLike

chagrinnamontoast

July 14, 2013

“I also don’t understand why the universe needed to be so incomprehensibly enormous. It actually makes me angry sometimes, especially when I can’t find a place to park.” Excellent point! And very funny!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 15, 2013

Thanks, Misti. It does seem like a great waste of space, doesn’t it?

LikeLike

bitchontheblog

July 14, 2013

Is that all it takes to engage you, Charles – for a long time: An astrophysicist? I shall forthwith drop everything and study my socks off. Giving me the edge. See you soon.

U

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 15, 2013

Thanks, Ursula. What I’d really like to know about is pulsars, which are extremely dense collapsed stars that can rotate hundreds of times per second. This doesn’t seem possible. Most descriptions of pulsars compare them to a spinning figure skater, in the sense that when the skater pulls in her arms, she spins faster and faster. I guess that works, except that a collapsed star has no arms. Or skates. I also wonder what kind of score the pulsar would get from the Martian judge.

LikeLike

Elyse

July 14, 2013

Astronomy is way over my head. But I do think that calling those toll free numbers should be required of all 5-9th graders. Because they can no longer do prank phone calls. I think this would be the next best thing.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 15, 2013

I agree, Elyse. Those operators who are standing by would appreciate the calls, too, I imagine. It might help them stay awake.

LikeLike

georgettesullins

July 14, 2013

What a quirk of fate if you have hit on something here…like the person on the other end of the 800 number may be, could be intelligent life from another galaxy. I have always been skeptical of intelligent life in other galaxies because it seems to me they would have have already found us…perhaps they have and are simply just an 800 call away. I’ll say “thank you” for the thought, and you can say “you’re welcome.” But then you may not see things that way.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 15, 2013

I’m not sure they would have found us, Georgette. It’s possible to be extremely intelligent — like dolphins, whales, and parrots — and have no way of leaving the planet or producing technology that would allow long-distance communication. On the other hand, maybe the universe really is teeming with intelligent life, and we just haven’t been invited to the party.

LikeLike

Lady from Manila

August 9, 2013

I agree with you, Charles. There’s no doubt the universe is brimming with various forms of life. What’s more, I have this strong suspicion said life forms are made up of stuff that are absolute deviations from our Earth’s physics. My mind has visualized of planet dwellers possessing of gas-like or liquid anatomy, or of something completely foreign to our senses. MInd-boggling, don’t you think?

And most likely, if we can’t find them, neither can they find us. 🙂

Religion versus science. That makes my head throb. But I’ll be up for it next time. Perhaps. 🙂

LikeLike

Andrew

July 14, 2013

I’ve never thought of calling the 800 number on the Twizzlers package but I’ve often wondered about what kind of person would take the job of answering that number. What kind of training do you need? Is there a school that trains people for this? And why does twizzlers need an 800 number? Seems just as complicated as the big bang theory to me.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 15, 2013

I have no idea, Andrew. It says on the package that you should call if you have comments or questions. I keep trying to come up with a question about Twizzlers that wouldn’t make me sound foolish, but no luck so far.

LikeLike

Sandra Parsons

July 14, 2013

Your initial picture had me say: Yeah! He’s hit the nail on the head! Because I once found a jar of apricot jam that had a picture of apricots on the tag and it actually said “serving suggestion” and I tried to come up with a creative way of molding jam up in the shape of apricots in order to serve it. Needless to say I ended up just putting the jar on the table with the lid open.

As to your underwear drawer, I find that this does not happen when I only buy new undies as soon as I have tossed an old pair. Which is exceedingly hard for me because I will rather mend them than throw them away, so I have a lot of really old panties. But at least my underwear drawer is relatively easy to close.

Now, since I don’t have anything intelligent to say on the topic of astronomy I will leave you here. I am, as always impressed with the quality of your writing and the thoroughness of your research. Nice read, thank you, Charles.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 16, 2013

Sandra, there’s a theory that if the universe stops expanding and begins to collapse, time will run backward — people will grow younger, and broken cups will re-assemble themselves. Then, I guess, that apricot jam will return to its original form as whole fruit. This is all starting to fit together, don’t you think?

LikeLike

strawberryquicksand

July 14, 2013

Did you ever consider that that period-sized (we call them full stops, by the way… much nicer) dot that contained the universe had to be inside something? Like… another universe? Like, what’s at the end of the universe? A convenience store? That sells full stop sized universes? I could go on all day!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 16, 2013

Yvette, that’s one of those mind-boggling concepts — where did the Big Bang take place? Maybe I really need to find a few astrophysicists and interview them. Remind me to mention your convenience store theory to them.

LikeLike

strawberryquicksand

July 16, 2013

Hahah rather it would be an inconvenience store, I would imagine, as not accessible to particularly many people… 🙂

LikeLike

icedteawithlemon

July 14, 2013

If astronomers ever discover a galaxy with inhabitants who have an “aptitude for abstract conversation,” I will be nominating you to serve as the earth’s liaison. Perhaps after you have dazzled them with your intelligent discourse, you can invite them over for popcorn and Gilligan’s Island reruns–and then teach them how to prank call toll-free numbers. Won’t that be fun?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 16, 2013

As usual, you overestimate me, Karen. But I’d be willing to serve as the Earth’s representative, as long as I don’t have to dress up.

LikeLike

earthriderjudyberman

July 14, 2013

I can tell you for certain – or at least as far as I’m concerned – that there is life out there. It’d be arrogant to think that out of all the galaxies, ours would be the only one to have life.

Other than that, thanks for the thoughtful post. I didn’t know the Horsehead Nebula was that impressively huge. Wow!

Serving sizes are another matter indeed. Some breakfast cereal makers think 1/2 cup is sufficient. Others, 3/4 cup. But if your pour out the amount you’d like to eat, without measuring, you will get about twice as much or more that the “recommended” serving size. That might be worth a call. 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 16, 2013

Those serving sizes seem designed to simply boast about low calories, Judy. And about life in other galaxies, or even in our own — I hate to say this, but I don’t think we’re ever going to find out.

LikeLike

morristownmemos by Ronnie Hammer

July 15, 2013

You may speak of galaxies and infinite numbers, but let’s get back to the Kellogg’s cereal for a second (a fraction of a light year). The answer to your dilemma involves whether the cereal is sugar coated or not. A quarter cup of Fruit Loops is far more dangerous than a quarter cup of bran flakes. But if you put them together and send them off toward the Horsehead Nebula there’d probably be a violent solar eclipse followed by a traumatic tsunami. And that will determine where Edward Snowden eventually gains citizenship.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 16, 2013

I don’t think bran flakes and Froot Loops have ever been combined, Ronnie. It seems far too dangerous — maybe even more dangerous than a violent solar eclipse. (And Froot Loops really is spelled that way. I called the toll-free number to check.)

LikeLike

Martin Tjandra

July 15, 2013

I’m just thinking, how it would be a wonder, if just can cram my wandering thought just as brilliant as you are in this article. I would have TONS of articles by now. haha! Nice thought. I often wondered about the space too. But as it’s outside of my reach, so I will only dream about it for now. 😉

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 16, 2013

Thanks, Martin. We all have something important to say, so just keep writing.

LikeLike

Allan Douglas (@AllanDouglasDgn)

July 15, 2013

I think they made it all up. Astronomy’s version of Sasquatch and the Loch Ness Monster. Just stories astronomers tell each other as they sit around a camp fire. Astronomers are an odd bunch.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 16, 2013

Yeah, but they sure can fill up a blackboard.

LikeLike

ShimonZ

July 15, 2013

A beautiful read. Thanks.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 17, 2013

Thank you for taking the time, Shimon.

LikeLike

reneejohnsonwrites

July 15, 2013

Maybe that’s where my trees went – Horsehead Nebula. Is there a person I can write to there to ask if they have been located?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 17, 2013

There is, Renee, but your life will have returned to its normal orbit — including some new young trees — long before the message arrives.

LikeLike

Amy

July 15, 2013

I’ve never called the 800 number on the back of a Twizzlers package, but back in the 90’s when OK Soda made its brief debut in the world, I called the 800 number listed on the can. I got what seemed like an infinite recording of calls from other callers who had called the 800 number on the can to document just how “ok” OK Soda had made their lives.

I, too, spend countless seconds turned into hours pondering over such things as you’ve voiced. If I had it to do over again, I’d call the 800 number on the OK Soda can and tell them I’m not actually “ok”; “I want answers, dammit!” But then, I think I would miss the time invested in my ponderings…

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 17, 2013

The lesson of OK Soda, I guess, is that telling people you’re mediocre doesn’t work, because they believe you. And nobody wants to settle for OK — not when Coke and Pepsi can fill your life with non-stop excitement.

LikeLike

The Sandwich Lady

July 15, 2013

A great read, Charles. I always wondered what was outside that period that eventually became the universe? Was it an 8 1/2 by 11-inch sheet of paper?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 17, 2013

I don’t know either, Catherine, but I’m going to find out. I’m just not sure who to ask.

LikeLike

Sarah

July 15, 2013

Since I’m not that intelligent and therefore can’t speak to your larger-than-life quandaries, the best I can do is tell you what happened to the castaways on Gilligan’s Island. They spent 15 years there, then were rescued. It was a made-for-TV movie, appropriately called Rescue from Gilligan’s Island (1978). Here’s a link:

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 18, 2013

Fifteen years? Just where was this three-hour tour? And how hard would it have been for someone to trace the intended route and figure out where these people were? The Howells were millionaires, for crying out loud. Weren’t their financial advisers worried? I think it was a conspiracy. Did you ever notice how, just when they were about to be rescued, someone would look the wrong way or do something stupid to mess things up?

LikeLike

charlywalker

July 15, 2013

Yes I have called the Toll free line on many products as my daughter has a peanut allergy and needed to get specifics on their product; made my first call over 22 years ago re: peanut residue on their cookie presses. Called numerous companies after that ,ergo the result of the addendum added on the ingredients: “may contain traces of peanut”….

Yes I was responsible for that. & Yes there are real people there, especially if you mention Law Suit…..

As far as the castaways? Gilligan..the skipper too….. the millionaire and his wife, are deceased. The Professor AND Maryann are out of rehab, The movie star and the rest ..are alive and well on the Island of Manhattan……

Great Post..got a Bang out of it!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 18, 2013

I’ve seen that peanut warning on products that would seem to have no reason to be anywhere near peanuts. I guess the threat of a lawsuit really works.

Thanks for the comment, CW.

LikeLike

Anonymous

July 15, 2013

The castaways were rescued, except for Ginger. Tina Louise wanted too much money. Oh, and the Professor was the hotness back in the day. Nobody could turn a coconut into a radio like he could.

As for the rest… my head hurts.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 18, 2013

I’ve always wanted to know this, and I have a feeling you’re the person to ask: Was Mrs. Howell’s name really Lovey, or was that Thurston’s pet name for her? I’d research it myself, but I don’t trust Wikipedia.

LikeLike

scribblechic

July 15, 2013

This reminded me of a childhood game where I would hide in plain sight, convinced my form could be sheltered by the space of a thumb as I blocked out the world around me with a stubborn squint. Of course this sounds ridiculous now (I can only imagine how I must have appeared to my mother), but back then I felt indulgently powerful.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 18, 2013

I did something similar. I’d put my hands over my eyes, because I was sure that if I couldn’t see them, they couldn’t see me. It’s a good thing we’re a lot smarter now, isn’t it?

LikeLike

tlnokia

July 15, 2013

Reblogged this on tlnokia.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 18, 2013

Thank you.

LikeLike

silkpurseproductions

July 15, 2013

My filter of my own limited, human experience seems really small. This whole thing is too big for me.

As for Gilligan and the gang. They got rescued in a really bad movie. Just know it didn’t end well…or anything else well for that matter.

I have called the number on the back of my liquorice package it just wasn’t Twizzlers. They were in New Zealand and they were really helpful and very nice to chat with.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 18, 2013

I’ve had the Australian licorice, but never any from New Zealand. What exactly did you chat about, Michelle?

LikeLike

silkpurseproductions

July 18, 2013

I have a thing about licorice and have tried it from every where. RJ’s is the absolute best. This is their website.

http://www.rjslicorice.co.nz/ It is very hard to find and when a store gets a shipment of the black licorice in it sells out very fast. When I called them I hadn’t expected to get a real person because some disaster had just happened in NZ. I can not remember what it was for the life of me, it could have been fire or flood or earthquake…I just can’t remember. Anyway, we did chat about that for a bit. I told the woman how much I enjoyed her licorice and what a freak I was about it and how hard it was to find. I wanted to know what stores carried it and if you could just order directly. Apparently it is easier to get on the West Coast. She looked up the distributor for the GTA and gave me his information so I could contact him directly. I had mentioned that I was in the US frequently if there were places that carried it there. We had talked for quite awhile and she finally said, “You know, Michelle, you can order it online in the US and have it shipped to a US office.”

Crazy! Right? We just kept talking. She was pretty determined to help me find some licorice. I even wrote a blog about this licorice.

Aren’t you glad you asked? 😉

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 19, 2013

I was just thinking what a great job that must be, to answer the phone and talk to people about licorice. It would be like being the flower delivery guy — everyone is happy to see you.

LikeLike

lostnchina

July 15, 2013

The enormity of the Universe eludes me about as much as real live people answering those 1-800 numbers on the cereal boxes. I remember when they used to have contests on the boxes way back when (ie. Mail in a piece of the box for a prize, or some such thing), and I remember calling to ask why they never sent me the *thing* (probably a coupon towards a future purchase). It’s a recording, Charles. It’s a cereal conspiracy, and I think you should address this in a future post. We should refuse to be treated shabbily by the Fruit Loops/Lucky Charms/Trix/Cap’n Crunch people!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 18, 2013

I fell for the scam, too, Susan. You had to mail in five box tops, or something. I usually received the item, but it was always a big disappointment.

LikeLike

marymtf

July 15, 2013

Civilians are always asking, ‘where do you get your ideas’. Ideas are easy, I’m always explaining, it’s what you do with them that’s hard. I always look forward to seeing what you’ve done with your ‘little’ ideas. PS. What is it that we loved about Gilligan’s Island all those years ago? I watched a couple of episodes on Foxtel recently and couldn’t pick it.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 18, 2013

I’m not sure, Mary. One of my favorite shows when I was a kid was Bonanza. I watched an episode recently and couldn’t believe how bad it was. I think even the trees were fake.

LikeLike

Aakash Adesara

July 16, 2013

Your freelance writing is absolutely fantastic. I enjoy the way you incorporate humor and information into your posts. Could you please visit my blog at http://www.aspiretheninspire.com and give me some tips/advice on how to improve my post quality?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 19, 2013

Thank you for the kind words, Aakash. I just visited your blog, and thought it was well done. I hope you’ll both keep up the great work. People hear so much bad news. They need inspiring stories, too.

LikeLike

Aakash Adesara

July 19, 2013

Thanks for your compliment! People like you keep me going!

LikeLike

Stacie Chadwick

July 16, 2013

Dear Charles,

You should be writing for someone, like the New York Times. You’re that good.

=)

Stacie

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 19, 2013

Thank you, Stacie. Maybe we should promote each other, since we’re so pathetically bad at promoting ourselves.

LikeLike

Philster999

July 17, 2013

I think the universe HAS to be expanding. That would explain why my waist line seems to be getting a little bit bigger every year. Hey, it’s science — who am I to argue? (Pass the donuts, would ya…)

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 19, 2013

It’s just another part of the paradox that the donuts themselves seem to be shrinking. Have you noticed that?

LikeLike

shoreacres

July 17, 2013

You know, all the way through this I kept thinking, “I’ve heard this discussion before”. I just couldn’t remember where I’d heard it. Now I know. At least cranky old Job got himself an answer!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 19, 2013

Linda, the discussion sounds familiar because it’s part of our ongoing struggle with unfathomable mysteries. Through science and religion, we’ve created explanations that — to me — are equally incomprehensible. If we feel compelled to latch onto a solid answer, it’s because the brain we happened to be born with sifts through the facts (or what we perceive to be the facts) and tips the scale in favor of one side or the other. I’ve said this before, but I don’t think we decide what to believe. If the Bible clears away the chaos and provides the relief of certainty for some, I’m glad. For me, the questions will always outrace any answers our minds can contrive.

LikeLike

shoreacres

July 19, 2013

It was the timelessness of the conversation that caught me, not the certainty of the answer(s) – which, after all, aren’t answered even in the Bible. Besides, I just like Job. 😉

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 21, 2013

He is a relatable guy. And after reading about him, it’s easier to feel grateful, and lucky.

LikeLike

Sue

July 17, 2013

Charles you gave me a smile this morning…thanks. I was late reading your post due to the flood damage in my basement from the Toronto storm last week. Needless to say I called several 1-800 numbers this past week and talked to people all over the world. The first was to my insurance company and my call landed in Montreal after a 40 minute wait. The next was to Direct Energy because my water heater died. A wonderful lady in Sarasota Florida solved my problem and I had a new heater the same evening. The next call was to Sears to find out how old my washer and dryer were and a nice young girl in the Philippines answered.

The poor thing had a cold and was working the night shift…..I think I woke her up so please don’t call any of those numbers. You never know where they will answer or at least ask where they are located. It might be Mars the next time..

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 19, 2013

Sue, I’m sorry to hear about your troubles. It seems there are problems with flooding from one end of the country to the other. The fact that you were willing to wait on hold for forty minutes to talk to your insurance company is no doubt a reflection of how bad things must have been. It’s also a sign of the times that we can contact people all over the world to help us with our local situation. I hope things continue to improve for you. And thank you for the nice comment.

LikeLike

Bruce

July 19, 2013

An entertaining read. I’m one of those that thinks the universe goes forever; I only wish I could be on a ship finding out. Down to more earthy matters; I had a good laugh with you sometimes being angry at the enormity of the universe. Thanks for that Charles. Your post also brought to mind Dr Seuss and his story, Horton Hears a Who. An elephant called Horton lives in a jungle and discovers a city (Whoville) existing on a speck of dust. Sort of a double perspective.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 19, 2013

Bruce, I remember seeing Horton Hears A Who on television many years ago. The movie that came out more recently was also very good. I’d gladly go along with you on that ship, but it would have to travel faster than the speed at which the universe is allegedly expanding. As with most things concerning life here on Earth, I’m afraid we would just keep falling farther behind.

LikeLike

Bruce

July 19, 2013

Who knows Charles; we might get lucky and hitch a ride on some Star Trek ship with a blinged warp factor which can get us to the edge. Fingers crossed and we could blog on the way. Meanwhile, the mention of the universe allegedly expanding seems to confirm what is common sense to me. For anything to expand there must be space (is this a pun?) around it.

LikeLike

Wyrd Smythe

July 19, 2013

“I also don’t understand why the universe needed to be so incomprehensibly enormous. It actually makes me angry sometimes, especially when I can’t find a place to park.”

ROFLMAO!! For me, that was the best, funniest line in a very funny piece!

I’m no astrophysicist, and any real one will tell you there is much we don’t understand (so I surely don’t), but I’ll take a stab at it. (Although, Charles, I always feel like I’m somehow spoiling the joke when I step up with some science here. I’m never sure I shouldn’t just sit down and shut up.)

The laws of physics are the same everywhere and at every scale. That’s actually a central tenet of physics. Simple mechanical machines can’t crush a car past coffee table size, but if they did have the technology to remove all empty space, the car would end up too small to see. The reason scientists think they know what happened moments after the BB started (and ever since) is because we assume the physics was the same. It’s through using physics as we know it to calculate what must have happened that we think we understand the BB.

Atoms, as you say, are almost entirely empty space. Imagine a sphere large enough to contain a 20-story building. If that were an atom, the electrons would be the size of dust motes, and the nucleus would be a grain of sand at the center. That’s all the substance atoms have. (And that’s effective size. As far as we can tell, elemental particles (electrons, neutrinos & quarks) have no physical size; they are truly dimensionless points.)

The singularity behind the BB was pure energy, no particles (they came later when stuff “cooled” and the particles “froze out”). Certain particles (electrons, for instance) obey the Pauli Principle which disallows more than one with the same state. Being in the same place is part of being in the same state, so the PP is one reason everything doesn’t all just collapse into itself. Energy doesn’t follow the PP, so there is no restriction on how much energy you can pack into one spot.

As for Gilligan and friends, I think we can let the truth out. They were very clearly CIA agents cleverly inserted to a tropical island to monitor our enemies during the Cold War. Their high-tech gear was disguised with coconuts and bamboo to allay suspicion. Now you see why they brought so much gear. Code name “Gilligan” was their leader and mastermind, an agent of such genius that he fooled everyone. Of course, Mr. Howell was the money man. Code name “Skipper” was their enforcer. “The Professor” was their “Q” and of course the young ladies were Mata Hari-types.

Clearly all their attempts to leave the island had to fail if they were to remain in place to carry out their mission. Success was obtained only through Gilligan’s brilliant “fumbling”. (As you may recall, the island was several times visited by foreign agents, which is why the “castaways” had to remain under deep cover.)

Next time you watch an episode, keep all this in mind, and things will make a lot more sense!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 21, 2013

I’ve been waiting for your comment, WS. In fact, I was thinking about you while writing this post — although I didn’t expect such a thorough analysis of Gilligan’s Island. I never trusted the Howells, but couldn’t imagine that even Mary Ann was up to something.

Your description of the atom is a perfect example of how difficult it is for our brains to understand reality on the very large and very small scales. Our experience takes place on our human scale, and so when I try to imagine an atom the size of a building with electrons as dust motes and a nucleus the size of a grain of sand, my mind insists that everything should just collapse like cotton candy. And then, I can’t close my suitcase because I threw in that extra pair of pants.

About that infinite energy packed into the singularity: believers in a creator will continue to ask, “Where did all that energy come from?” There was a time when I might have turned to the Professor for answers, but now I just don’t know.

LikeLike

Wyrd Smythe

July 21, 2013

That is one of the challenges of science: our daily experiences can be a poor guide to understanding some of what goes on in the very large and small scales. Just consider how, across a very broad spectrum of electro-magnetic energy, we directly perceive only that very tiny slice we call “visible light.” It does tend to make science a bit abstract, which is part of what makes it hard for many to grasp.

The off-the-cuff answer to your question about energy has to do with Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle. That’s the one that says, for one, that you can’t accurately know both the position and momentum of a particle. It also says that space and energy are mutually exclusive. The more you know about space, the less you know about the energy of that space. How do you “know” about space” By localizing. The smaller you localize space, the less you know about how much energy is in that small space. If the space gets “infinitely” small, then energy is allowed to be “infinitely” big.

The Big Bang supposedly happened when an infinitesimally small piece of space decided it had a whole universe worth of energy. KABOOM went space, and the rest, as they say, is cosmological history. And apparently due to “negative” energy, when you consider the universe in the right way, the negative and positive energy cancels out, so there really isn’t any energy at all. Just seems to be.

Yeah, I know. I don’t get it either.

I see Mary Ann had you completely fooled! 😀

LikeLike

greenroomgallery

July 20, 2013

Hi Charles, Yes, I also think of all those things interchangeably. When it comes to electrical cords of any kind, it puzzles me that I always tangle them in with random objects. But what really shut me up a few years ago was Canis Majoris. I include a link and some info for your perusal.

http://www.tumblr.com/tagged/vy%20canis%20majoris

VY Canis Majoris is the largest known star and one of the brightest. It is about 3 billion km in diameter and 4,900 light-years from Earth. It is relatively unique when it comes to stars in that it is a single star, rather than multiple star systems. VY Canis Majoris is so large, that if an airplane traveling 900 km/h were to circle it, it would take over 1100 years to make one journey!

As always, you cheer up my day, thanks for that. 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 21, 2013

Thanks for that link, Charlotte. The comparison of Canis Majoris to our sun reminded me of the recent and somewhat ongoing debate about poor little Pluto. It was stripped of its status as a planet, in part because of its relatively small size. Can you imagine a scientist insisting that the sun should no longer be considered a star?

LikeLike

Betty Londergan

July 21, 2013

I spent a day at the Adler Planetarium in Chicago in March, and I felt like my head was going to explode. But what really fried my chaps was when I read that all those gorgeous photos from the Hubble had the COLORS ADDED — they’re actually just all in black and white! Boy, if that didn’t make me want to give up on understanding String Theory and stick to cereal boxes instead….. Great post, Charles!!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 22, 2013

And then there’s the fact that our eyes and brains can interpret just a sliver of the electromagnetic spectrum (see Wyrd Smythe’s second comment, above). What’s black and white to us would look completely different to some other species that can see (or perceive) in other wavelengths. Uh oh — I think my head just exploded.

Thanks, Betty.

LikeLike

Wyrd Smythe

July 22, 2013

Those false color photos allow us to “see” the universe in ways that would be impossible (and really boring) with just visible light. Assigning colors to invisible wavelengths brings out the incredible beauty of the cosmos.

Speaking of how our eyes see, check out the Mantis Shrimp:

http://theoatmeal.com/comics/mantis_shrimp

LikeLike

Lady from Manila

August 4, 2013

Boy am I glad I chose to read this awesome post on my Sunday afternoon as it is the subject I don’t mind pondering about for hours in one sitting. You see, there’s a certain book titled “Modern Earth Science” I earnestly carried around with me everywhere in junior high school – primarily for its chapter on astronomy. Sky-watching is a cherished activity I can’t get enough of, too. And visiting the city’s Planetarium remains as a favorite childhood memory of mine.

I’ve expressed my offbeat notion in another pal’s blog that our universe could just be a part of a much larger something. Or that our universe may not be alone. I don’t know. That’s what makes it so darn exciting. Nobody is absolutely sure about anything out there – yet everything is so breathtakingly beautiful.

All things come to an end. Will the universe be one of them? Probably. Though I hope it never will.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 7, 2013

It’s strange, isn’t it, how much we care about the fate of the universe? Whatever is going to happen is probably billions of years in the future. Chances are, we won’t be around to see it. Yet the idea that it may all dissipate into nothing upsets us somehow.

LikeLike

Lady from Manila

August 11, 2013

That it could dissipate anytime is unthinkable yet dreadfully possible. 🙂

I’d like to take this opportunity to express the fact you’ve never ceased being instrumental to my happiness in our blog universe. Maybe I unintentionally tried your patience with my silly nonsense and our differing convictions in the past. The truth remains clicking on your blog and seeing you consistently writing your heart out on the subjects that you care about are enough to keep me feeling contented whenever I spend time in this blogosphere.

I hope everything’s well with you, Charles.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 11, 2013

All is well. There’s nothing to worry about. Please let me know how you’re doing.

LikeLike

whatsapp

September 24, 2013

Thank you for another informative blog. The place else

could I get that type of info written in such a perfect means?

I’ve a undertaking that I am just now running on, and I’ve been on the

glance out for such info.

LikeLike