I peer out the window on a sunny July afternoon, scanning right and left, and covering the full semicircle within view. All is quiet, and still. The scene is unsettling, like a dream that’s disturbing for a reason you can’t quite identify. Two bicycles lie on their sides in the driveway next door. A basketball has rolled under a parked car and appears to be wedged under the back bumper. There’s a single black crow glued to the roof of the house across the street.

I peer out the window on a sunny July afternoon, scanning right and left, and covering the full semicircle within view. All is quiet, and still. The scene is unsettling, like a dream that’s disturbing for a reason you can’t quite identify. Two bicycles lie on their sides in the driveway next door. A basketball has rolled under a parked car and appears to be wedged under the back bumper. There’s a single black crow glued to the roof of the house across the street.

Nothing moves.

If an alien spaceship were to hover over the block, activate its vertical vacuum system, suck all the people into a sealed compartment, and disappear without a sound, this is exactly what the result would look like.

Where is everybody? When did summer become a time of mass evacuation?

* * * * *

I’m twelve. It’s the last day of school. A little while ago, I leaped off the bus and said goodbye to the seventh grade. Our neighborhood is alive, swarming with dogs and kids, all trying to out-bark each other. There are no electronic devices, and the first text message is decades away. When you want to get someone’s attention, you cup your hands around your mouth and you scream. If they don’t hear you, then you take in a big gulp of air and scream louder. Or you throw something at them.

I stand off to the side and close my eyes. In my mind, I can imagine the entire vacation sprawled out in front of me, stretching away almost endlessly into the future. This is the best part of the best part, and I want to squeeze the moment, holding onto it for as long as I can.

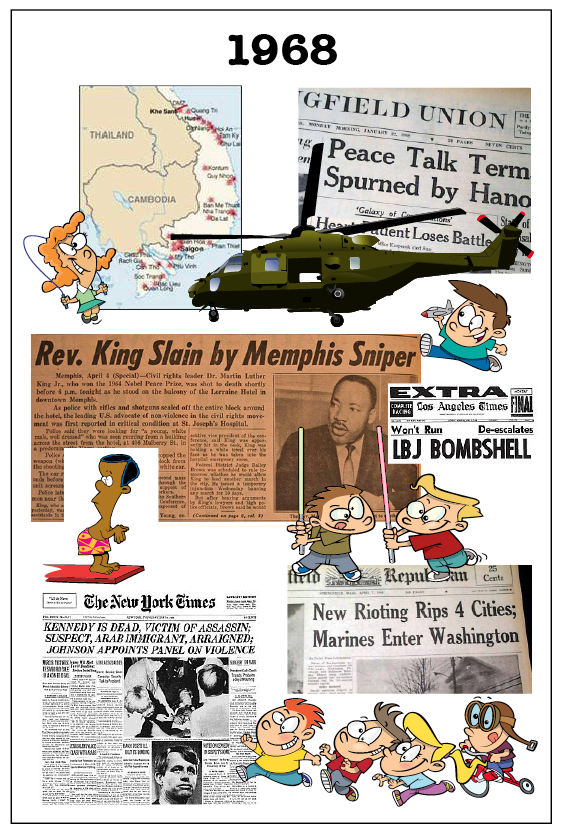

It’s 1968. We’re only six months in and it’s already been a terrible year. Actually, every year is terrible, but something happens to your brain when you turn twelve. You begin to look outward, and see things you hadn’t noticed before. You start to examine the differences between what you once believed about life and what seems to be the case in the real world.

The civil rights movement is riddled with violence as peaceful protests turn into battlegrounds, and the murder of its leader sparks national riots. The democratic process in the United States is marred by assassination and police brutality. American casualties in a far-off country reach a peak of more than sixteen thousand, while civilians there are massacred because sometimes “it becomes necessary to destroy the town to save it.” At the Nevada Test Site, no fewer than fifty-six nuclear weapons are detonated, with the force of each bomb measured in thousands or millions of tons of TNT.

Things are so bad that even the president, up for re-election, decides to head for the hills.

Meanwhile, on the suburban streets of New York, children employ less menacing strategies for dealing with conflict. Small factions of boys, divided by some pointless disagreement, launch missiles of stupidity back and forth across a demilitarized zone of empty pavement.

The fighting stops abruptly when someone announces, “Your mother wears army boots.” This silences everyone, not because it’s especially shocking or clever, but because nobody really understands what it means, and a careless reply could expose that embarrassing truth. During my childhood, I expend countless volts of mental energy trying to visualize the mother of one friend or another trudging up the stairs in oversize and clunky military footwear. The image eventually evaporates into a calming mist of nothingness, which, I now suppose, is just what it was.

When somebody does manage to say something genuinely cutting, we struggle in vain to respond in kind.

“Yeah, so’s your old man” is often the best we can do. If an action or comment is considered too far out of bounds, we offer up the vacant threat – “I’m telling” – which is just vague enough to be intimidating.

“You’re in trouble!” is equally effective, but only if the word trouble is stressed, with a sufficient gap between the syllables, and is delivered in a sing-song tone, as though it could just as well have been a dire warning chanted in Latin.

“You’re in trouble!” is equally effective, but only if the word trouble is stressed, with a sufficient gap between the syllables, and is delivered in a sing-song tone, as though it could just as well have been a dire warning chanted in Latin.

One day, an older girl sends a hush through the crowd. She’s done something ill-advised, and has been called on it. But rather than shrink away, she stands tall and defends herself by declaring, “It’s a free country!” We all shut up. We’ve never heard this before, and have no counter-argument. Four little words that seem to carry so much weight, and are uttered with such authority, that we’re sure they must have come from an advanced history class, or one of those thick volumes with no pictures I sometimes encounter at the library while I’m searching for books of jokes and riddles. It soon enters our language, and we use it to justify almost anything. In fact, we have a supply of stock answers to help us prepare for most situations.

When we’re caught by surprise, we say we weren’t ready, and ask for a do-over. When something gets in the way, we yell “Interference!” When we want to claim our preference, we do so with our voices: “I called the front seat.”

Somehow, it all works. No one is killed, or beaten with clubs, or dragged off to jail, or even expelled from the group. We keep the peace through verbal sparring sessions, and if there are emotional wounds, they heal quickly and are gone.

* * * * *

As I stare out the window on another sunny July afternoon, I wonder if emotions ever get wounded on this street. Do the kids who live in these quiet homes — and who have now been assigned to camps and soccer tournaments and other organized activities – ever learn to explore the boundaries and solve their own problems? Or will they simply re-assemble in early September, seated at their desks and secretly sending each other text messages, while their teachers attempt to explain war, discrimination, and the uncontrolled rage of mobs? And will they grow up, still not knowing how to be together?

* * * * *

Here’s one of the biggest songs from 1968.

* * * * *

nerdinthebrain

July 5, 2013

This post makes me sad for modern kids…and nostalgic for running around with a pack of kids all summer. (Oh, how I did enjoy a good game of Wall Ball!)

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 5, 2013

I never played wall ball, but we did play a variation of it — something like baseball, with the wall serving as the batter. We also played stoop ball. Now I really feel old.

LikeLike

Thoughtlife

July 6, 2013

What is wall ball? Is it like curby? We had a game called curby, to do with carefully judging distance and trajectory to make a ball rebound back to you from the opposing – your opponent’s – curb. This piece, reminds me of how long summer used to feel when I was a kid, and try to imagine what those hot eventful days in the sixties – things I’ve only witnessed through newsreel – could have been like to experience. Thanks for the read.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 6, 2013

We played curby, too, although we may have called it curb ball. If you managed to hit the corner of the curb just right, the ball would really take off.

LikeLike

Patti Kuche

July 5, 2013

Gosh Charles, I haven’t heard “I’m telling!” for years. That was the go to defence for everyone and everything. Our poor parents and teachers, or TMI as the SMS might say now.

LikeLike

Patti Kuche

July 5, 2013

And just the other day my son asked me about something historical that happened back in the day and all I could answer was “1968” because everything seemed to happen that year.

Including long haired bearded organists wearing fantastic psychedelic shirts, it really was the end of civilisation as far as my parents were concerned.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 5, 2013

Civilization has ended quite a few times since then, Patti. But 1968 was a memorable year in a lot of unpleasant ways.

LikeLike

jeanjames26

July 5, 2013

I think I hear “I’m telling” at least once a day from at least one of my kids along with “You’re not the boss of me!”

My dad saved The Daily news papers from 1963 Kennedy’s assasination and 1969 landing on the moon. I’ve framed them and hung them in my house as little pieces of living history for my children to hopefully understand some day.

Tomorrow I’m off for a road trip out west, making my street 3 kids quieter.

I loved your song choice to wrap up your very entertaining post.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 5, 2013

Jean, I have quite a few of those old newspapers and Life magazines, too. Framing the covers sounds like a great idea. Of course, that’s right when their eBay value will skyrocket.

LikeLike

Allan Douglas (@AllanDouglasDgn)

July 5, 2013

Ahhh, wouldn’t it be wonderful if we could use “I’m telling” to defuse international stress and use rock, paper, scissors instead or bombs, bullets and gas to settle conflicts? I wonder if our techno-gadgets and the social fragmentation they cause will hurt our ability to resolve differences. I suspect so, since instead of shouting “Your mother wears army boots” or “So’s your old man”, now school kids tend to shoot one another.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 6, 2013

Sad but true, Allan. Regarding the “I’m telling” approach, I guess the United Nations was supposed to serve as the authority figure when countries stepped out of line. It doesn’t seem to be working.

LikeLike

Andrew

July 5, 2013

I remember my friends and I sitting around and doing the “So what do you want do?”

“I don’t know, what do YOU want to do?”

We could that for hours. We never had much conflict, it was more of a group indecision and often ended up just riding our bikes up and down the street.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 6, 2013

That reminds me of the scene from Jungle Book:

LikeLike

silkpurseproductions

July 5, 2013

Wow! You certainly have me waxing nostalgic. It was a different time. 1968 was the year in between my Mom’s illness (1967) and her death (1969). I vividly remember her reaction to all that happened in 1968. It must have been horrific for her to imagine leaving her children behind in the world that had gone mad. She couldn’t have known it could get worse.

We were roughly the same age you and I (I didn’t turn 12 until March of 1969) and I remember all the Rascals songs but I don’t think I ever thought about who sang them until now. Thank you for providing a musical interlude.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 6, 2013

It was a strange time, Michelle. The Cold War was the worst of the madness — because of what could have happened — but we seem to have replaced that nightmare with a lot of hideous reality. We’re just not smart in the right ways, are we?

LikeLike

earthriderjudyberman

July 5, 2013

The death of JFK in 1963, and the deaths of MLK and RFK in 1968 … ended my innocence. They were devastating and, I believe, changed our world forever. Vietnam! It’s no wonder that LBJ bolted and opted not to run for re-election.

Your thoughtful post, Charles, can be applied to adults as well. This quote of yours in particular: “Small factions of boys, divided by some pointless disagreement, launch missiles of stupidity back and forth across a demilitarized zone of empty pavement.”

If only we could get along and respect each other’s differences. Then we could all live to play another day – happily and safely – in our neighborhoods.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 6, 2013

Judy, I keep thinking most of our problems come from the fact that we tend to follow the wrong leaders. Could it be that simple?

LikeLike

earthriderjudyberman

July 6, 2013

Charles, when I read Douglas Adams “Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy,” a character in that book changed my thoughts about those in high office. Zaphod Beeblebrox made me realize that our leaders are only figureheads who respond to the whims of those in the smoke-filled rooms – not to those who elected him.

LikeLike

Wyrd Smythe

July 6, 2013

I don’t think so… because then the question is, “Well, why do we do that?” One thing does seem certain… it’s not our leaders… it’s us.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 6, 2013

Yes, it’s us — because we’re the ones who are too lazy or afraid (or ignorant) to see that we’re giving power to people who won’t use it wisely or generously. It’s bad enough that we’re dumb, but do we have to keep letting it surprise us?

LikeLike

Chichina

July 5, 2013

Such a thoughtful, yet entertaining blog. Your words always bring me back to my own childhood in southern Ontario. Strange how we grew up miles and miles apart in two different countries, and yet the colloquialisms and strategies for conflict resolution were the same. I just returned from my daughter’s home in B.C. where she lives on an acreage home to three goats, twenty or more chickens, three dogs and one cat. She runs a licensed day care for a number of children, which includes my two grandchildren aged five and three. The majority of her children are four and under. My daughter and her husband are growing their own vegetables, and also have a number of fruit trees and berry bushes. The chickens provide eggs as well as food, and the goats provide milk and cheese. I had the honor of observing her day-care which she advertises as an outdoor daycare, the premise being that children need to run and jump and play. Imagination is what guides their play and when they have a conflict she encourages them to use their words, explain how it made them feel, and resolve it on their own. These children dug in the dirt, made up games, rode their bikes and totally entertained themselves without complaint. The three goats hang out with them This is what children need. They don’t need virtually every aspect of their lives planned out to the minute. They don’t need expensive toys, and they don’t need to be seduced by electronic gadgets, or god forbid, anesthetized by TV. It’s a sad and empty world for children today, when the streets are bereft of the sound of their voices. What have we done?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 6, 2013

I don’t know what we’ve done. It seems that we’ve put up too many barriers — between individuals, but also between people and the natural world. We’ve become afraid of everything. I think your grandchildren, and the others in your daughter’s daycare, are very fortunate. You must have many reasons for wanting to be there, too.

LikeLike

creatingreciprocity

July 5, 2013

Best thing I read all day.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 6, 2013

Thank you, Trisha.

LikeLike

subodai213

July 5, 2013

You’re right, In a lifetime of good years, bad years, 1968 stands out as perhaps the worst. I was 14-old enough to understand the horrible assassinations of men who didn’t have it coming, dealing with the aftermath of riots in Detroit, when entire neighborhoods were burned to the ground (which happened in 1967-but which spurred the white flight to the suburbs, of which we were merely one family) and trying to grasp what my older cousin, just back from his second tour in Viet Nam, meant when he kept saying “goddamn it, Tet. Goddamn it, Tet.” It was such a horrible year.

And yet, as you said: it was still a lovely summer, even though it was full of things like moving vans and finding oneself an utter stranger in a suburban sea of kids.

as for the ‘your mother wears army boots”…having lived in combat boots for 21 years, I can tell you, they’re good, comfortable boots. Ugly, yes. Having to spit shine them was the worst. Never having had kids, I never got the opportunity to hear that. Although we had one young kid in the ‘burbs with a funny accent who used to say “your mother swims out to the troop ships.” THAT was incomprehensible at the time, but now……..whew.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 5, 2013

We left the Bronx for the suburbs in 1966. Entire neighborhoods in the South Bronx burned down, too, but that was mostly in the early ’70s — when I was back there for college.

Oh, wait. I grew up in Detroit, didn’t I?

LikeLike

subodai213

July 6, 2013

You did. I remember you. You were that cute altar boy who could run faster than I could..;-)

LikeLike

subodai213

July 5, 2013

Oh, yeah, I forgot, because at the time it didn’t strike me: but wasn’t the Kent State massacre in 1968? Jeez, what a horrid year.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 5, 2013

Kent State was actually 1970, but definitely the same era.

LikeLike

Sue

July 5, 2013

Our reply to any of those old taunts was – I know you are but what am I….it could be repeated til the cows came home.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 6, 2013

“It takes one to know one.” We used that a lot, too.

LikeLike

Wyrd Smythe

July 5, 2013

I think it’s one of the great questions of our age. All this “Global Village” technology, all this connectedness and information… Is it, as so many feel, a destructive force in society? Or is it just change? What comes out the other side of all this?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 6, 2013

It seems likely there will be a range of results, WS — some good, some terrible, and a lot in between.

LikeLike

Wyrd Smythe

July 6, 2013

I tend to agree (when I’m not feeling particularly dark about things). I suspect we’ll do what we always do: muddle through. I still worry about what kind of society we’ll create. Have you ever seen Mike Judge’s Idiocracy?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 6, 2013

No, but I just read about it, and it sounds like something I’d like. I’m going to look for it. Thanks, WS.

LikeLike

Wyrd Smythe

July 6, 2013

I suspect you’d like it. It takes the “Marching Morons” concept (from Kornbluth’s 1951 SF story) and extends it to its logical future conclusion.

One thing that struck me when I watched it the first time: “Ah, ha! I’m not the only one who thinks so!”

LikeLike

kasturika

July 6, 2013

I remember my friends screaming from outside… And I remember memorizing phone numbers of friends, when phones still had wires attached to them, and it was usually their parents who picked up the phone… They say technology has led to connectivity… really?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 6, 2013

We’re more connected to people in far off places, and with people we would otherwise have no chance of ever meeting — you and me, for example. But that connection too often comes at the expense of those right around us. I think we need to try harder to find a balance.

LikeLike

cat

July 6, 2013

1989 was my year to remember … for ever … “kids mature so much earlier these days” … my mumme used to say back then … ya … mature, alright … by 1972 my family intended to marry me off, as the custom was in our culture … I was mature enough to run … just some snippets of thoughts of mine … sorry, probably doesn’t make too much sense to you, Mr. Bronx Boy … thanks for stopping by my blog a while a go as well … Love, cat.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 7, 2013

That handful of years between childhood and adulthood are always a confusing jumble, cat. I’m glad you did what you needed to do back then.

When I visit your blog, I’m never sure if my comments are making it through.

LikeLike

Elyse

July 6, 2013

I do feel, too, that never letting kids just figure things out — how to relieve boredom, how to get along with different sorts of people, stepping in and solving all their problems, is bad for the kids and bad for the country. We’ve only taught them dependency.

Great post, as always!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 7, 2013

I know every generation in history has complained about its children, but I do think we’re becoming less able to tolerate boredom, time alone, inactivity, and any kind of discomfort. I remember noticing, when my kids were little, that if the temperature was above 73, they complained that it was too hot. If it dropped below 68, they said they were cold. Their comfort range, then, was a narrow five degrees. This seems to apply to many areas of modern life. We’re gradually losing our stamina.

LikeLike

Wyrd Smythe

July 7, 2013

“I do think we’re becoming less able to tolerate boredom, time alone, inactivity, and any kind of discomfort”

Head. Nail. Hit!!

LikeLike

Strings 'n Things

July 6, 2013

I have the same worries for the young people of today (30 and under!). Will they know how to relate? Thanks for bringing back memories of the 60’s— you were a mature 12 year old it sounds like, noticing all the unrest of those times.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 7, 2013

It was hard not to notice, Rae Ann. Making sense of it was another matter.

Thank you for the comment.

LikeLike

Snoring Dog Studio

July 6, 2013

I came back to the U.S. from Japan in 1968. I had spent three years away being oblivious to the world – my world – the U.S. 1968 was a grueling year for me. We had moved to Texas, which was fairly godforsaken then as well. Life kept changing and I couldn’t figure it out. No one in my family seemed to be able to figure it out. We just struggled in the long hot summers of Texas. I remember a lot of violence then that year and for a few years afterwards. Was it Texas? Or was it the world?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 8, 2013

I don’t know that anyone ever managed to figure it out. After the JFK assassination, it seemed as though everything was doomed. The war in Vietnam was a hopeless mess. The Apollo 1 fire killed three astronauts. Johnson decided not to run, then Nixon and Agnew resigned from office, then Ford lost the election, then the hostage situation in Iran, then Carter lost his bid for re-election. Mixed in there were the MLK and RFK assassinations, the Democrats’ convention in Chicago, Watergate, Kent State, riots all over the country, and a lot of other really terrible things. It’s like we got pushed down a hill and we haven’t been able to regain control yet.

LikeLike

Snoring Dog Studio

July 8, 2013

Sigh. Yes, it does seem that way.

LikeLike

rangewriter

July 6, 2013

“You begin to look outward, and see things you hadn’t noticed before.” This is so true! I wondered if it was just me or everyone who began thinking outside the ‘hood around this age. Perhaps it was the unrest of the 60’s that got us looking outside the ‘hood.

I really like the way you flesh this out by demonstrating the slow turning of the 12 year olds’ vision from inside the playground to the larger world. Really nicely done.

I worry that today, without those street encounters that you remember, kids come home from camp armed with new ways to hack and electronically bully their classmates. We all recognize how much more powerful a written slam can be.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 8, 2013

I guess after the smug decade of the ’50s, we thought we were unstoppable — kind of like how teenagers have no sense of their own mortality. So we never even saw the wall before we slammed into it.

You’re right about electronic bullying. So much more damage can be done these days, with much less risk to the person causing the problem.

LikeLike

Jennie Upside Down

July 6, 2013

🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 9, 2013

I still have no idea how to do those smiley faces.

LikeLike

Earth Ocean Sky Redux

July 13, 2013

I was just having this discussion with friends Maineiac – of letting kids out to play. That’s how many of us grew up – out the door, saying bye mom with be home for dinner the typical response. We were on our bikes to far away places, climbing trees, making forts, wading through streams, swimming in a neighbor’s pond. My mother could whistle like crazy, the four-fingers to the lips loud type, and we knew that meant we better get home! That was the extent of our supervision and we never thought our parents were neglecting us.

Today’s kids, or maybe it’s more accurate to say today’s PARENTS, don’t let that freedom ring much anymore. Out of fear, real or perceived, that children having fun will actually bring about harm. Sad.

Happy to hear YOUR children get the freedom to explore, be imaginative, and as I heard Ward Cleaver say the other day, “if you have to tell your mother where you are going, it would take away all the fun of going”.

LikeLike

She's a Maineiac

July 6, 2013

This summer I was thrilled to have nothing planned for my kids. No camps, no sports, no play dates. We just kinda wing it from day to day. I do hear “I’m bored” plenty but I do what my mom did to me, I shoo them outside. So far it’s working because they come back completely exhausted, happier and calmer.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 9, 2013

I think you’re onto something there, Darla.

LikeLike

Earth Ocean Sky Redux

July 13, 2013

FYI: My comment above was a reply to Maineiac July 6th comment but I clicked the wrong reply button and it posted farther above where it makes no sense.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 14, 2013

Thanks, EOS. I sometimes have trouble getting a comment or reply to land where I want it.

LikeLike

Paula J

July 7, 2013

I like your writing so very much. It really takes me back.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 9, 2013

Thanks, Paula. I’m glad to hear that.

LikeLike

Stacie Chadwick

July 7, 2013

Charles,

Your post gave me chills. Literally, because I mourn the loss of long summer days with my friends where the whole world seemed to stretch out in front of us…everything and nothing to do day after day. Our kids don’t run up and down the street, a virtual band of brothers, like I used to with my friends back in the day. They’re in camps and art class because every kid on our street is in camp and art class. It’s sad.

Thanks for writing such a thoughtful post. Love it.

Stacie

P.S. How did you know that my dog and kids are constantly trying to out bark each other? =)

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 9, 2013

Stacie, I wonder if those days and experiences are gone forever, or if we’re in the middle of some kind of pendulum swing. Maybe sometime soon, parents will discover that kids can come up with ways to fill their own time and make their own decisions. Meanwhile, the kids — like my son — who don’t go to art class and camp, will spend a lot of summer vacation time feeling lonely and bored.

LikeLike

lolarugula

July 7, 2013

Oh, for the days when the summer stretched out forever before us! Great memories here, along with some funny and sad recollections of my own that were conjured up. Wonderful post.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 9, 2013

I try to remember why the summers seemed so long back then, and I can’t. Was it because we were thinking more about what to do, so we were more aware of the time? I find now that weeks and even months go by in a blur.

LikeLike

icedteawithlemon

July 7, 2013

“Small factions of boys, divided by some pointless disagreement, launch missiles of stupidity back and forth across a demilitarized zone of empty pavement.” There you go again, so vividly describing scenes from my own childhood–except our demilitarized zone was someone’s brown grass front yard.

I really enjoyed this post, Charles, not just because you evoked fond memories but also because you identified what was always a key concern of mine while sitting in my principal’s chair–parents micromanaging their children’s lives (scheduling every free minute, making every decision, fighting every battle) instead of allowing them “to explore the boundaries” and learn how to organize, decide, and solve on their own. In our quest to give our kids the best of everything, too often we have failed to give them the most important gift of all–the ability to think for themselves and to learn from their mistakes.

Stepping off the soapbox . . . love the song, too! I’ll be singing it the rest of the day, which isn’t a bad thing.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 10, 2013

It must have driven you crazy to see so many parents hovering over their kids, as well as the ones who were completely uninvolved. Why is it so hard to find a balance that works?

LikeLike

estherlou

July 7, 2013

I graduated from high school in 1968. I couldn’t remember the song until I went to listen to it. Then, I thought it was pretty lame, and remembered it sounding better than it did! LOL

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 10, 2013

It was written in response to the band’s witnessing some pretty serious racist behavior in the late ’60s, which makes it one of those songs that, unfortunately, is still meaningful.

LikeLike

shoreacres

July 7, 2013

You know what else happened in 1968? The 5.4 Illinois earthquake on the New Madrid fault. I was sitting in my kitchen outside Cedar Rapids, Iowa, when I heard a slight jingling and then watched my water glasses walk off their shelf. When I think back, it seems somehow appropriate that the earth should have moved actually as well as metaphorically that year.

There’s increasing evidence that children who are kept in an antiseptic bubble, never exposed to germs, never allowed to get cuts and scrapes and never given the chance to learn how to pick themselves and their bikes up off the ground and go on – by themselves – are at increased risk for asthma, allergies, and terminal whining while they wait for someone else to come and “make it better”.

It seems to me that’s the same dynamic you’re talking about, albeit in a slightly different context. If I were the Queen of the World (a thought that actually goes against my better judgment, but never mind) the first thing to go would be participation trophies. Next would be the ban on best friends in grade schools. Then, we could deal with reinstating dodge ball. You get my drift.

Life is tough. Sometimes it hurts. Sometimes it’s no danged fun at all. But when I was a kid running loose with the pack in the neighborhoods on summer evenings, it wasn’t tough at all. It never hurt, and it was a good bit of fun. When the street lamps came on, we all ran to our homes, still laughing (or in some cases, pouting or crying). But no one ever had to call us, and someone always was there.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 10, 2013

Linda, in addition to the asthma, allergies, and terminal whining (I was tempted to substitute attitude there to complete the alliteration), children seem to be taking much longer to grow up. I know parents who are waiting for their thirty-year-old kids to move out.

They’ve banned dodge ball?

LikeLike

blackgirlsurvival

July 8, 2013

Great post! My mother really did wear army boots.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 10, 2013

I think the effect of the statement came from the fact that all verbal assaults had to include something about the other person’s mother. It almost didn’t matter what it was.

LikeLike

marymtf

July 8, 2013

As I remember it, Charles, and my memory isn’t what it was, the Cold War was about a stalemate. The US and Russia were at a stalemate and neither dared to move, which is why it was a cold war (actually my memory is what it was only it’s getting worse than it was). Now that both sides are providing the makings for WMDs to two other sides of another conflict, the cold war is readying itself to heat up. You delivered the goods yet again.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 14, 2013

You’re right, Mary. The stalemate was fed from both ends by a constant replenishment of newer and bigger nuclear weapons. It’s happening again, just without the terrifying headlines.

LikeLike

aynotes

July 9, 2013

Reblogged this on aynotes's Blog.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 14, 2013

Thank you.

LikeLike

Damyanti

July 11, 2013

As usual, your post gives me a lot to think about, Charles. I keep bookmarking your posts on my phone, meaning to comment later from the laptop, and by the time I get to it, I forget what I wanted to say. Oh, well.

This post does remind me of my own Indian childhood of playing on my street with kids in the neighborhood, and negotiating my way through those years relatively unscathed. I don’t know what kids in Singapore do. The ones in my condo play an occasional game of basketball, but remain otherwise invisible.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 14, 2013

I’m not surprised, D, that your childhood was similar to mine, and that things are pretty much the same today in Singapore as they are here. The world has changed, I guess.

It’s good to hear from you. I hope you’re doing well.

LikeLike

Bruce

July 12, 2013

Great post Charles, worry with a smile. I kind of hope that a bit of ‘everything old is new again’ will happen, especially with the kids. So many kids and ‘grown ups’ seem to be together more than ever from eyes open in the morning till eyes closed at night. I couldn’t handle so much company. The cyber world allows this but prevents them from dealing with each other face to face. The Rascals video isn’t playing by the way; some copyright issue is to blame. I’m telling.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 14, 2013

Sorry about the video, Bruce. That happens to me all the time, with copyright issues preventing replay in Canada.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 14, 2013

I just checked and now I can’t even watch it. Nice.

LikeLike

scribblechic

July 12, 2013

This was my first read upon returning home. I share similar concerns and consciousness for the dramatic differences between my childhood experiences and my children’s. Still, you have a lovely gift for framing awareness by the light of nostalgia.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 14, 2013

Thanks for the kind words. I hope you had a great trip.

LikeLike

winsomebella

July 12, 2013

I am reminded how universal the childhood experience can be—though you and I are the same age, I spent my early years in Kansas—reading this made me feel as if I grew up a block over from you :-). My mom would stand on the front porch at dark and whistle for the four us. She was a good whistler—-we could hear her five blocks away, signaling to us it was time to head home quick.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 14, 2013

My mother used to open the front door and yell for us. Each mother had her own unique call, so the kids knew who was being summoned home.

LikeLike

Marusia

July 14, 2013

Here, in Brazil, people are on the streets, protesting against corruption. There are many students, most of them had never participated in a demonstration before. Some results started coming, some laws, some public policies. I want people to be proud of the accomplishments, but actually I hope they can vote right next elections. I believe that voting is the most powerful (and effective) kind of demonstration.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 14, 2013

I agree about voting, Marusia. Still, it’s good to hear that some people are still passionate enough to go out and voice their opinions.

LikeLike