Someone sends me a link to a video. I click on it, and within seconds I’m watching a man who seems to be striding on foot across the surface of the Thames River. Onlookers in the video are leaning over railings and peering from windows, pointing at him, astonished at the sight. I ignore the speed at which I’m able to access these images – or the fact that I’m able to access them at all — and immediately slide into a frame of mind that is both skeptical and critical.

Someone sends me a link to a video. I click on it, and within seconds I’m watching a man who seems to be striding on foot across the surface of the Thames River. Onlookers in the video are leaning over railings and peering from windows, pointing at him, astonished at the sight. I ignore the speed at which I’m able to access these images – or the fact that I’m able to access them at all — and immediately slide into a frame of mind that is both skeptical and critical.

“Do these people think he’s actually walking on water? Why are they so gullible? I’ve seen this trick before, and it never had me fooled.”

Even as these thoughts scuttle through my head, I’m analyzing them too, as well as the negative comments posted by previous viewers. When did we become so impatient, and so difficult to entertain? How did we grow so accustomed to the flashes of magic in our lives that we no longer recognize them?

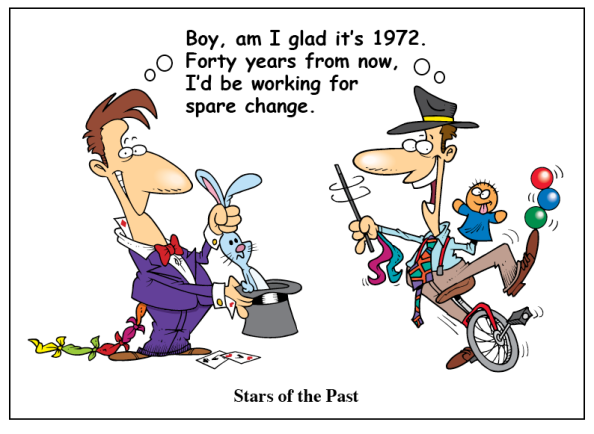

It was once easy to impress us. In fact, we were pushovers. I can remember spending a small chunk of my Sunday nights watching an overdressed hyperactive man spinning plates and bowls on live television. Professional magicians pulled flapping birds out of the air and sawed women in half. A guy juggled hats while riding a unicycle and playing the harmonica. A lady in tights emerged from a basket that was no bigger than a bowling ball bag. I sat there with my eyebrows going in one direction and my mouth in the other, and wishing it would never end.

In the decades before the Internet and DVDs, when attending a real show was no more affordable than a Cadillac or a self-cleaning oven, we were hungry for the tiniest morsel of amusement. That’s why we could appreciate almost any diversion from daily life.

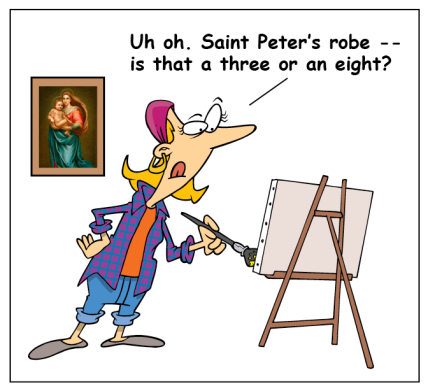

My mother used to crank out paint-by-number masterpieces that she later framed and displayed all over the house. These were mostly religious scenes, rendered in oil and with great precision: a portrait of Jesus, the Three Wise Men, the Last Supper. Until then, I had been familiar with only the paintings I saw hanging on walls at restaurants, or as postcard-size reproductions in school. My mother, I was convinced, would someday be as famous as any of the well-known artists. Although I didn’t realize it, there was magic in those hidden numbers. She had other tricks, too. Faced with a stubborn jar of applesauce, we’d all take turns struggling to pry it open. Minutes later, facial veins popping and hands bearing the imprints of our failure, we’d back away, mumbling something about not really being in the mood for applesauce. Then my mother would take a spoon from the silverware drawer and tap it around the lid, hard, the way they smacked prisoners of war who refused to talk. We’d witnessed the procedure a hundred times, and each time we were sure it wouldn’t do any good, even though it always did. She’d grasp the jar with one hand and twist with the other, and the lid would turn and come off without a fight, as if that’s what it wanted to do all along. To this day I don’t understand it, but the magic was in the tapping.

She had other tricks, too. Faced with a stubborn jar of applesauce, we’d all take turns struggling to pry it open. Minutes later, facial veins popping and hands bearing the imprints of our failure, we’d back away, mumbling something about not really being in the mood for applesauce. Then my mother would take a spoon from the silverware drawer and tap it around the lid, hard, the way they smacked prisoners of war who refused to talk. We’d witnessed the procedure a hundred times, and each time we were sure it wouldn’t do any good, even though it always did. She’d grasp the jar with one hand and twist with the other, and the lid would turn and come off without a fight, as if that’s what it wanted to do all along. To this day I don’t understand it, but the magic was in the tapping.

Our house wasn’t filled with things. This was partly because most things didn’t yet exist, but also because there would have been no place to put them. We had no basement, attic, or garage. We had no vacuum-sealed pouches or stackable plastic crates with snap-on covers. Christmas ornaments, winter gloves, used baby clothes, and hundreds of black-and-white photographs were stored in cardboard boxes, high up on shelves in the hallway closet. Each box had four flaps that, when folded in the correct order, stayed closed without benefit of tape or cord. My father used this technique often, his hands moving in a blur that I attempted to follow, with scant success. Slow-motion instant replay would have helped, but we didn’t have that either. I close boxes this way myself now, although there’s an area of my brain that still can’t quite believe it works. Tying my shoes, wrapping a gift, and dialing a telephone all produce the same reaction. The magic is in the sequence.

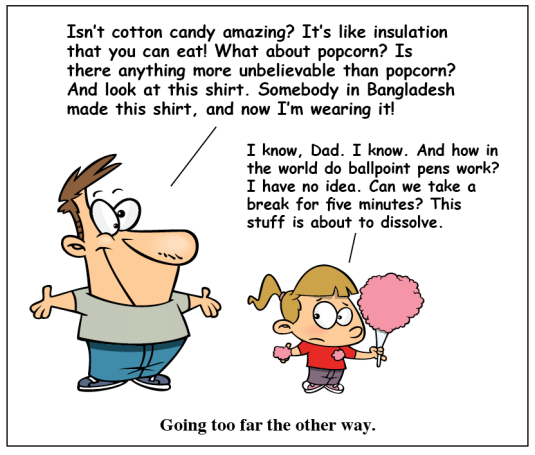

I’ve seen cotton candy being made, up-close, with my face inches from the operation. There are no discernible moving parts. Yet sticky pink threads appear from nowhere, collecting and building to a soft, fluffy bundle around a paper cone. And then, like ghostly particles that emerge and vanish in the quantum world, the cotton candy returns to nothing at the slightest contact with heat or moisture. The magic, I suppose, is in the machine. I don’t know exactly what’s happening in there, and I’m not sure I want to.

I’ve seen cotton candy being made, up-close, with my face inches from the operation. There are no discernible moving parts. Yet sticky pink threads appear from nowhere, collecting and building to a soft, fluffy bundle around a paper cone. And then, like ghostly particles that emerge and vanish in the quantum world, the cotton candy returns to nothing at the slightest contact with heat or moisture. The magic, I suppose, is in the machine. I don’t know exactly what’s happening in there, and I’m not sure I want to.

Sometimes it’s better to be left wondering, and to always have something within sight and within reach that will get us wondering again. I’m filled with that sense of surprise when I watch someone play the piano, knit a sweater, or fix a leaky pipe. There really is magic everywhere. But we have to know where to look, and how to look. Usually, it requires just slowing down and paying attention to details.

On the larger scale, however, I’m afraid we’re too easily disenchanted. Even the Apollo missions to the Moon couldn’t hold our interest for long, and by the third one we were already bored, treating them like summer reruns. And that was in the early seventies, so we were the same people who put up with The Newlywed Game for eight years.

There’s no doubt we’ll continue to grow more demanding. You can make the Golden Gate Bridge disappear? And you’ll do it while standing on the water in San Francisco Bay? That’s nice. But how many plates can you spin? Have you ever opened a jar of pickles with a butter knife? When was the last time you painted the Mona Lisa?

It was fun to see magic in the little things, and to allow ourselves to feel astonished. I liked being amazed that someone could juggle hats, stay up on one wheel, or play the harmonica.

I want to be a pushover again.

shoreacres

April 5, 2013

Nice post, that evoked three immediate thoughts, in no particular order:

1. Where has all the magic gone? It’s right here.

2. I’m afraid we’re too easily disenchanted. Even the Apollo missions to the Moon couldn’t hold our interest for long, and by the third one we were already bored, treating them like summer reruns. And that was in the early seventies, so we were the same people who put up with The Newlywed Game for eight years… As Tonto said to the Lone Ranger, “What’s this “we” [business], Kemosabe?”

3. There’s a soundtrack for your post!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 5, 2013

2. It was a collective “we,” as in “We went to war” or “We won the World Series.” Someone has to take the blame. Okay, I’ll admit it: I did see the show a few times. But that was back when there was one television in the house, and the people who paid for it got to decide what to watch.

LikeLike

Coyotemoonwatch

April 5, 2013

Triggers thoughts of National Geographic: When I was a kid, there were wild, untamed, newly discovered things and places written about and photographed in each monthly edition. Now it seems it’s all scenes of inner-city ghettos and oil-drilling landscapes and war zones. Same sort of sense of loss for it all.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 5, 2013

For the first time in my life, I just subscribed to National Geographic, and I’ve noticed the same thing. Where’s all that beautiful photography I remember?

LikeLike

architect of the jungle

April 6, 2013

Maybe the magazine is placing more emphasis upon depicting ruined beauty as a way to get us to stop abusing the planet…just a wild guess.

LikeLike

pendantry

April 14, 2013

It’s entirely possible that the beauty is actually being eroded away; we don’t notice it because it’s happening in slow motion. There’s a term for this, but it escapes me atm.

WRT the magic: if you can’t juggle, I recommend learning the skill. I found that a terrific way to remind myself that there are still things around that appear to be impossible, but aren’t. As long as you believe it can be done, you can be juggling a three ball cascade within an hour… it helps if you can find a juggler to coach you while you try; the secret is not to worry about catching; the difficulty is in learning to let go.

LikeLike

architect of the jungle

April 14, 2013

I’d like to learn how to juggle. An older boy in college once tried to teach me how to do it with oranges in the sleepy motel lobby where he worked. I was terrible, my mind and body wouldn’t comply; maybe if there hadn’t been a curfew I would have had more time to learn to keep the oranges from falling to the ground. Then again, learning how to juggle in front of anyone, let alone your crush, might be a setup.

LikeLike

pendantry

April 14, 2013

the secret is not to worry about catching

Your hands know how to catch, they do it automatically. Forget about catching, just learn to throw the balls… at first it will be all over the place, until the rhythm comes, and suddenly it clicks.

There’s lots of juggling tuition stuff on t’innerwebz.

LikeLike

"HE WHO"

April 5, 2013

Charles, you never let me down. This post has inspired a surge of memories, I still tap around the lid (after running hot water over it for a few seconds) to open troublesome jars. I wish I could still eat cotton candy. I remember the jugglers and magicians on the Ed Sullivan show (and waiting patiently for Topo Gigio).. It was all magical! Of course, so was Gerald McBoing Boing on the radio, before we ever got a TV. I had almost forgotten my father playing “Lady of Spain” on his harmonica. Jerry and the Harmonicats had nothing on him. Thanks for the reminder. I do appreciate it.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 6, 2013

I have an entire DVD of Topo Gigio appearances. But now I’ll have to go find out who Gerald McBoing Boing was.

Thanks for the comment, HW.

LikeLike

Andrew

April 5, 2013

Yes, what happened to the plate spinners? I use to like watching them on Ed Sullivan but you just don’t see many around any more. Now if “American Idol” had a category for plate spinners or jugglers, I might actual watch that program…

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 6, 2013

Jugglers are still around, but even they have had to raise the bar. I saw a guy the other day who solves a Rubik’s Cube while he’s juggling it and several other objects. Show off.

LikeLike

scribblechic

April 5, 2013

My son once said, “Adults over think possibility.” Children are magicians, illuminating magic between the mundane.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 6, 2013

When my daughter was very young, I noticed that she could watch the same video a hundred times. In fact, she insisted on it. Eventually, I figured out that she was seeing something new every time. I think that must be the secret.

LikeLike

susielindau

April 5, 2013

I believed in magic when I was young along with Santa and the leprechaun, but as we age, we are told about the reality of life and something dies inside us. I think that part of me still longs to be re-lit as I tend to be one of the more gullible in the crowd.

I still believe in the power of positive thinking which is huge when your really embrace it. If you believe in that, then anything is possible!

BTW- I have seen jugglers on America’s Got Talent!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 6, 2013

I love reality, Susie. In fact, I think that’s where the real magic is. We just stop noticing it after a while. That must be one of the reasons people like to travel — the unfamiliar is automatically exciting.

LikeLike

icedteawithlemon

April 5, 2013

“How did we grow so accustomed to the flashes of magic in our lives that we no longer recognize them?” I wish I knew. Maybe in our attempts to focus on “the big picture” and not to “sweat the small stuff,” we have lost sight of all the little miracles, all the flashes of magic and magnificence, that surround us every day.

Great food for thought, Charles. And yeah, I want to be a pushover again, too.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 6, 2013

Karen, I think you’re one of those people who’s never forgotten how to pay attention and find those little miracles. It’s evident in every one of your posts.

http://icedteawithlemon.wordpress.com

LikeLike

icedteawithlemon

April 6, 2013

Thank you, Charles. You are very kind.

LikeLike

Diane Henders

April 5, 2013

Lovely post, Charles. I think I must be a throwback to another age, because I still marvel virtually every day at electricity.

I’m a computer geek and a science geek. I understand how and why electricity works in terms of electron transfer. I can (mostly) understand circuit diagrams, and I can talk (semi)-knowledgeably about resistance and capacitance and diodes and stuff… but it’s still magic that I can stick a metal prong into a hole in the wall and make a bulb light up.

And don’t even get me started on the miracle of this inert black box in front of me that makes it possible for me to communicate with people around the world.

Wow. Just wow. 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 7, 2013

I feel the same way, Diane. And it doesn’t have to be a mystery, either. On those rare occasions when I can understand how something works, it becomes even more amazing.

LikeLike

dearrosie

April 5, 2013

I’m glad you put my thoughts into words.

In the current photography show [at the museum where I work] there are some photos (taken in the 1950’s) of a remote snowbound Japanese village. The villagers are poor subsistence rice farmers, there aren’t any shops so most probably the children have never eaten candy, or seen a magic show.

My favorite photos of the show =

1.When a monk came to the village the children followed him around like the Pied Piper.

2. At New Year’s Eve the children sit in an ice cave and sing songs to their visiting parents.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 7, 2013

Rosie, I know you’ve also seen many photos on Betty’s blog, showing people all over the world who just light up at the slightest novelty. Abundance, it seems, can be very depriving.

LikeLike

Paula J

April 5, 2013

“Our house wasn’t filled with things. This was partly because most things didn’t yet exist…” I love that line. Great post.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 7, 2013

Thanks, Birdie. I’m looking forward to your next post. (Waiting impatiently, that is.)

LikeLike

John

April 5, 2013

There is magic in the mundane and, as you wisely observed, it is in the details.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 7, 2013

One of the great benefits of blogging is that we can keep reminding each other of that, John.

LikeLike

Mame

April 5, 2013

I definitely get upset with our monkey trajectory. Progress for progress’ sake has become seriously stupid. The world deserves–or should I say NEEDS–to hit the brakes a little. What’s the rush?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 7, 2013

Some of the best places to find magic are historical restorations. I’m always stunned by what people were able to accomplish centuries ago, with little more than their hands and some ingenuity (and the willingness to work hard). “Monkey trajectory” — I like that.

LikeLike

bobcomeans

April 5, 2013

Charles, I draw caricatures at a renaissance festival eight weekends a year. The magic is there but as an artist, or a stage performer, you definetly have to work at it. The patrons are so not used to live interactive entertainment that it makes your job twice as hard. You get alot of mindless staring. The village is set in the 1500’s with the name of Newcastle, England. The only thing I wish was cotton candy had been invented so I could gladly partake. Mead and ale will only take you so far. Bob

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 7, 2013

I used to work the counter at a Dunkin’ Donuts, Bob, so I’ve seen that mindless staring. Maddening, isn’t it?

LikeLike

Ruth Rainwater

April 5, 2013

I think believing in magic requires imagination, and that generally gets knocked out of us shortly after we start school. And that’s a shame. It has taken me years to get back that sense of wonder I had as a child. I think we, as adults, get jaded by the realities of earning enough to feed, clothe, and house ourselves and our families.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 8, 2013

I don’t believe in the kind of magic that we find in fantasy and science fiction. In fact, I never read that kind of story, and can barely make it through those movies. I prefer the magic that comes from real life — the things that seem impossible, but somehow happen anyway. You and I communicating this way, for example.

LikeLike

Val

April 5, 2013

It does seem that a lot of the magic we perceived as kids has now gone, but I think it’s just that we don’t spend enough time daydreaming about the alternative dimensions of anything. Think of it, as kids, our heads are in another place altogether. Sometimes as we get older they ‘come together’ (in adults terms) but ‘fall apart’ (in kids terms). I’ve a post in mind that is on similar lines to this, hopefully I’ll write it in a few days.

By the way, you know those packet flaps? I only sussed out how to close a breakfast cereal packet to stop it coming undone in the cupboard, a few months ago! I’ve been doing it wrong all my life!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 8, 2013

It’s never too late to learn, Val. Do you have packaging that comes with a strip of sticky tape that’s supposed to hold a bag of cookies closed? They never work for me. I’m probably doing it wrong.

LikeLike

Val

April 8, 2013

No, they don’t work for me either (our packets of Basmati rice have those), so I just pull them off!

LikeLike

silkpurseproductions

April 5, 2013

The walking on water video disturbed me as well, but I couldn’t put my finger on why. Perhaps I thought that was one trick that only one person should be able to do. As far as magic goes…I see it in my 3 year old niece’s eyes every time she discovers something. Her eyes get big, she gasps, points and then laughs with joy. Well, that, and cotton candy, I haven’t figured that one out either.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 8, 2013

Michelle, I wonder if we’re just too insecure to show our amazement. Being puzzled or surprised means we haven’t seen something before, or if we have seen it, we haven’t figured it out. As adults, we’re supposed to know everything. My experience has been that when I admit to being mystified, there’s someone there who feels compelled to explain it to me. Knowledge is good, and almost always preferable to ignorance, but I still like the feeling of being amazed.

LikeLike

silkpurseproductions

April 8, 2013

I don’t know. The same fellow did a couple of other tricks in the same video and I was surprised by them or puzzled as you say but the walking on water thing just creeped me out.

LikeLike

Danlynn

April 5, 2013

Reblogged this on ~*~ Danlynn ~*~ and commented:

Very nicely written!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 8, 2013

Thank you, Danlynn. I hope the semester is going well.

LikeLike

Bruce

April 5, 2013

I love the detail and the kid with his teddy, makes me laugh.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 8, 2013

Thanks, Bruce. It’s always nice to get your feedback.

LikeLike

strawberryquicksand

April 6, 2013

If you truly want to be wowed, check out Australia’s Cosentino… http://www.cosentino.com.au/index.php/home01 He came second on Australia’s Got Talent a couple of years ago and his death defying magical feats are unbelievable. And if you want to be awed, and have your mouth and eyebrows go in those different directions, check out Soul Mystique, who perform the old art of quick change. It’s just unbelievable. It truly is. Check out their video gallery. I dare you! http://www.soulmystique.com/home

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 9, 2013

I checked out both, Yvette, and they’re both great. I really liked Soul Mystique, I think because they’re so smooth and quick, and there are fewer explanations (that I can think of) for what they do. The huge, spectacle-type illusions that magicians such as Cosentino perform are impressive as well, but I prefer the simple, up-close sleight-of-hand stuff. The card trick he did with the newscaster was amazing. Thanks for sending those links.

LikeLike

strawberryquicksand

April 9, 2013

My pleasure! I’m glad you enjoyed it. Soul Mystique are AMAZING. I have NO idea how quick change operates and even iuf it were possible to change that fast- what the heck do they do wtih the clothes!!!!!?

LikeLike

morristownmemos by Ronnie Hammer

April 6, 2013

You are so right. When my son was turning 6 we hired a magician to entertain the children at his party. The man arrived and asked me to give him some privacy while he “set up” his magic tricks. I was the adult, and was shocked that he wasn’t really doing magic, but tricks. I still think back about that and am amazed at how gullible I was: wanted to be…

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 9, 2013

Ronnie, have you ever watched a magician and been baffled by some illusion, and then discovered (or figured out) the secret? If so, did you feel completely let down? I always do. It’s a disappointment to learn the mundane explanation for what seemed so magical.

LikeLike

Philster999

April 6, 2013

I agree, “The magic is in the sequence.” Nice line — and obviously the secret to such engaging writing as well! PJ

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 9, 2013

Thanks, Phil. I’d never made the connection before between magic and writing. Both require a lot of behind-the-scenes trial and error before the finished product is ready to be shown. (At least we hope it’s ready.)

I really enjoyed your latest post:

http://philipjefferson.wordpress.com/2013/04/05/postcard-from-the-edge/

LikeLike

Patti Kuche

April 6, 2013

Your wonderful words bring back so many sweet memories, when as children we had the freedom to roam and share certain universal experiences such as the magic of music, from radios out on the streets, at the beach, everywhere! In absolute awe of the talent putting words and music together.

What happened to your mother’s paintings? We had the same gallery but they were always bought from the souvenir shop next to the church. More mysterious magic . . . .:)

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 9, 2013

I don’t know where those paintings ended up, Patti. My sister may have them.

The magic of music, yes, but the magic of the radio itself, too.

LikeLike

Tandi

April 6, 2013

One thing I love about being a doctor is the wonder, the magic and mystery about life. Who lives and who dies, and when. Science can’t explain it.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 9, 2013

Very true, Tandi. Medicine continues to make breakthroughs and treatments become more effective all the time. But despite what the science magazines keep telling us, the mystery of death is still here, and probably isn’t going away.

LikeLike

architect of the jungle

April 6, 2013

It’s much easier to grow magic from ignorance, I think. Perhaps this is why people always long for beginnings. At the start, when we know so very little, our imaginations rule the school. Then little by little, when we begin to glimpse just the edges of the way things really are, we get taken down a notch or two and are required to adjust our self-perception. I suppose this is what growing up is; it used to be a more merciful process in that it was incremental – this was the way it was in the analog world. You couldn’t move too fast through these developmental stages. But the digital world destroyed that pace, and now we are forced to learn lessons we are not yet ready to learn, forced to absorb imported knowledge that isn’t native to our own experience.

Maybe this collective loss of ignorance is what is making us more demanding. Maybe we are demanding something our psyches require – we are demanding a world that relieves us of the responsibility of understanding too much too soon. In a way this makes me feel compassion for us as demanding spoiled children. We didn’t know what we headed for, and only when we got there did we see what had been left behind.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 10, 2013

Your description made me think of a hot air balloon with a big hole in it. As the hole gets bigger, more and more air is needed just to keep the thing inflated. Maybe the wisest course of action is to endure the inevitable crash, and then start all over. (With a smaller balloon.)

I especially liked this: “Then little by little, when we begin to glimpse just the edges of the way things really are, we get taken down a notch or two and are required to adjust our self-perception.”

LikeLike

hemadamani

April 6, 2013

” we need to slow down and pay attention to details” how true!! I’m amazed when I see a beautiful bird or a butterfly. I still stop to see a plane flying overhead. And recently I’m enjoying watching the Disney movies with my grand- daughter again and again, and enjoying every time. Have seen ‘Cinderella’ almost twenty times and have enjoyed every time. Great post as always and evoked so many memories, of times when the littlest things held magic for us!! Thanks for reminding!! 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 10, 2013

Thanks, Hema. Hanging around with your granddaughter sounds like a good idea. She’ll give you plenty of reminders.

LikeLike

hemadamani

April 11, 2013

🙂 🙂

LikeLike

Tom Marshall

April 6, 2013

I think the magic is right there in front of us but we’ve been programmed to watch this show or buy this product as a substitute. It has been commercialized because capitalism won. I remember being amazed by the commercials as a boy, but when the product was in my hands it didn’t perform at all like the commercial. It was a disappointment.

I watched a flock of geese land in the field behind our house, their honks floating across the open space towards me; and I saw two seals, their noses thrust upward into the air, as they watched the gulls float overhead. The magic was there. I agree with you. I want to be a pushover.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 10, 2013

You’re definitely a pushover, Tom. Your eye for detail wouldn’t let you be any other way.

LikeLike

ShimonZ

April 6, 2013

It could be that a large part of the magic was the innocence of childhood. There is still that magic. But now it’s directed towards modern technology. Now young people can text sweet nothings for hours on their cell device… it’s not really that they have something to say. It’s the magic of the instrument. They are totally overcome with admiration. Beautiful peace. I enjoyed it. Are these fine illustrations your work as well?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 10, 2013

Shimon, I wish I could say the artwork is mine, but that would be lying, and I only lie when I know I can get away with it. The original cartoons were all done by Ron Leishman, whose work can be seen here:

http://www.toonclipart.com

LikeLike

earthriderjudyberman

April 6, 2013

Our interest in space launches was rekindled, unfortunately, by accidents that claimed the lives of several astronauts. Like you, Charles, I’m astonished that many are so easily bored by the extraordinary events in our lives and yet are hooked on mundane shows like the Kardashians.

Cotton candy! I loved watching that stuff being made – and really enjoyed eating it. Thanks for reminding us how wonderful it can be to rediscover everyday things … to see things again thru the eyes of a child.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 10, 2013

Thanks for the kind words, Judy. You’re right about our interest in accidents: there was a blip when Apollo 13 almost didn’t make it back. By the very next mission, astronauts were reduced to hitting golf balls on the Moon. On the rare occasions when I see what’s on television these days, I always think, “Man, we’re in trouble.”

LikeLike

rangewriter

April 6, 2013

I find the magic each time I find a new post from Mostly Bright Ideas in my Reader. And…I’m still baffled by the flap order required to close a cardboard box. All my old box flaps are bent to a fairthewell from my fumble-fingered failures to flap in the correct order.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 10, 2013

Believe it or not, Linda, I actually closed a box using the overlapping flap thing and then took a picture of it — but then I forgot to include it in the post. Here it is. Please be sure to notice how I’ve mastered this skill.

LikeLike

rangewriter

April 10, 2013

Wow! Well done! And you didn’t even have to mark each flap, 1,2,3,4, under/over. Impressive, Charles.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 10, 2013

It’s like I always say: Everybody is good at something.

LikeLike

Wyrd Smythe

April 6, 2013

This is why I love science! A world of unending awesomeness and exciting discoveries.

I find it impossible to be jaded in a world where a spacecraft is exploring Saturn and sending back amazing photos. Or upon (recently) learning about how freezing water in the Antarctic generates trillions of gallons of brine which sinks to the ocean floor and drives ocean currents worldwide. Or in following the latest progress at CERN. Or so many other things.

LikeLike

Sandra Parsons

April 7, 2013

I second this, WS, science is a neverending source of amazement and wonder for me with the added benefit that, the more secrets are unveiled the more open questions are generated to fill us with that sense of magic. The collective “us”.

LikeLike

Wyrd Smythe

April 7, 2013

Exactly so!

It might be good to use the word “wonder” rather than “magic” due to the unfortunate freight associated with “magic.” And I expect that what people usually mean is “wonder” anyway. (Such as when people talk about a “magical” relationship. What they’re saying is that it’s wonderful.)

Harry Potter is pure fiction; there is no actual magic. There is, however, an amazing world of wonder and beauty and awesome astonishingnessousity (so much so it deserves a special word).

Fiction is tons of fun, but reality can seriously blow your mind!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 10, 2013

Once again, we’re spoiled, and it’s made us lazy. Centuries ago, scientists spent their entire lives studying, cataloguing, and revising theories that eventually allowed us a glimpse into the mysteries of the natural world. Today it’s all there on a plate, waiting for us, and most people would rather hear about the latest celebrity romance, or divorce.

LikeLike

Wyrd Smythe

April 10, 2013

The thing that mystifies me is, after dealing with the real world all day long, why would watch more of it on your “off time”?

Meanwhile I just spent a fascinating couple hours reading the blog articles of a chemist. It was a series of articles under the category, “Things I won’t touch!” and involves some of the nastiest chemistry you can imagine. Stuff that can burn sand!

Sooooo much more interesting than, “Stupid things people do.”

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 10, 2013

There you go again, WS. Now I’m going to spend half my day trying to imagine trillions of gallons of brine. It’s a big world, isn’t it?

LikeLike

Wyrd Smythe

April 10, 2013

Incredibly so. For comparison, Niagara Falls, during peak season, has a flow rate of about 202,000 cubic feet (1,511,064 gallons)…

PER SECOND!

A trillion (American trillion, the one with 12 zeros) is hard to visualize. A stack of 1,000,000,000,000 dollar bills would be over 60,000 miles and could wrap around the equator twice and then some.

I’ll say it again… how do people not find this stuff utterly fascinating?

LikeLike

Margo Karolyi

April 6, 2013

Technology – ‘magic’ in and of itself – has, unfortunately, taken the ‘magic’ away from our daily lives. If we don’t understand something, we simply ‘google’ it to figure it out. So sad. I still think some things simply defy explanation and are, indeed ‘true magic’. You just have to believe. Great post (as always).

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 10, 2013

You might be right, Margo, but I don’t think it has to be that way. Technology can let us see so many things that were hidden from us before. I’m thinking of something like the Hubble Space Telescope, as well as the Internet that gives us access to the telescope’s images and discoveries. As with many areas of life, it seems to come down to our ability to resist laziness.

LikeLike

Sandra Parsons

April 7, 2013

I think there might only be so much magic around, and as it moves on to fill our children with wonder it naturally has to leave us. The other day I was delighting in my little monster playing with my husband. Daddy would hide a small toy in his hands, then distract the little one (“look, what’s this over there!”) and move the toy to a different place when he wasn’t looking. At almost 4 I’m afraid the little monster may not be fooled much longer but for now he is still flabbergasted at where the toy went when he blew 3 times on Daddy’s fists. Or maybe he is just playing along to keep the magic going. I find that’s all the magic I require these days. Silly mother’s brain.

LikeLike

Wyrd Smythe

April 7, 2013

Not silly at all! Your own story shows that the “magic” (wonder!) hasn’t left you at all!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 10, 2013

The magic isn’t over yet, Sandra. The four-year-old may be catching on, but there’s still a littler monster who’s getting ready to step into that role.

LikeLike

marymtf

April 7, 2013

Even freckles that suddenly appear on his arm are food for thought for my four year old grandson. Everything is fresh and new and magic when you’re young. Wish I had my magic back.

I’ve worked the tapping on the lid trick but haven’t impressed anyone with it.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 11, 2013

Maybe part of the problem is our ability, as adults, to take in so much information. Young children are focused on the small, so they can spend hours or days on something that we take in all at once — and eventually fail to notice.

About the lid trick: have you ever asked someone to explain how it works?

LikeLike

marymtf

April 11, 2013

You’re darn tootin’, Charles, I know how it works. As a grandmother and before that as a mother of young children I made sure I was prepared for any and all questions, except of course the one sthat came left of centre and constantly tripped me up.

LikeLike

jeanjames26

April 7, 2013

My kids are still little, so magic prevails…for now. For me there is nothing more magical than the computer. I really don’t understand how it works, and I don’t care. I just know that when I turn it on the world is at my fingertips, that is something my children will take for granted, and perhaps be bored with, but not me, I will be in awe to the end. I love your posts they are always so thought provoking and inviting.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 11, 2013

I think you’ve nailed it, Jean. We’re captivated by things that are dramatically different from what we’re used to. When your kids were born, computers were already part of the world, just like trees and toasters. But we remember typewriters, which were helpful but not all that mysterious. The computer isn’t just some modest improvement; it’s a huge leap, and one that most of us don’t understand. I don’t, anyway.

LikeLike

Elyse

April 7, 2013

I think the magic for me died when cotton candy turned to belly fat each time I had some. It’s black magic.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 11, 2013

I wonder if anyone has invented cotton candy with zero calories. Actually, if they have, I think I’d rather not know.

LikeLike

Elyse

April 11, 2013

Pink spun saccharine just doesn’t have the same panache.

LikeLike

saraaftab02

April 7, 2013

LOL Parents were supposeed to be smarter

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 11, 2013

They were smarter. It was just hard to tell sometimes.

LikeLike

Allan Douglas (@AllanDouglasDgn)

April 7, 2013

Coincidentally, I just watched a video clip (OK, it was yesterday) where a magician posed as a store clerk and tried to sell Insta-chicks to the stores patrons. Just drop this chicken shaped pellet into a cup, add water and pour out a live baby chicken. It was surprising how many of them “had to have some of these”. I think it originally appeared on the Tonight Show. I enjoy watching “magicians”, but gave up trying to figure out how they do it. And yes, cotton candy is magic. Have you watched them make that stuff? Definitely magic.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 11, 2013

Allan, I’ve watched a lot of magic tricks in settings in which the magician is selling a product. After you buy the trick from them, they tell you how it’s done. Almost always, when I learn the secret, I can feel my entire nervous system deflate a little, and I think, “Really? That’s it?”

LikeLike

Betty Londergan

April 7, 2013

I want to be a pushover again, too! My mom used to literally be brought to tears by the vision of hyacinths poking up out of the cold spring earth — and a snowfall would have her in ecstasy. Some days it seems I barely notice the weather around me when it’s the source of near constant miracles. I appreciate your suggestion that it’s all there for us, if we just really open our eyes to the magic (and cotton candy?? It’s like sucking on insulation but yeah… how delicious!!!)

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 11, 2013

You’re a pushover if ever there was one, Betty. Both of your amazing blogs (What Gives 365 and Heifer 12×12) are filled with the evidence.

I haven’t caused you to feel misbegotten, have I?

LikeLike

Marusia

April 7, 2013

Up to now, I still love the magic in automatic doors, magnets, facsimile machines and shared photos using whatsapp… oh. – and in your posts!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 11, 2013

I’m with you, Marusia. I’ll never understand wireless printing, or how radio waves make it through walls without becoming totally distorted. And I wasn’t kidding in that last cartoon: I’m really amazed by ballpoint pens.

LikeLike

Stacie Chadwick

April 7, 2013

I learned that jar opening trick from my grandmother and still use it to this day. Works every time!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 11, 2013

I know it works, but why? And equally confusing, why are food companies using a torque wrench to put lids on jars? Sometimes I think they’re glued on. How do elderly people with arthritis ever get those things open?

LikeLike

Stacie Chadwick

April 11, 2013

I have an answer to that question. Don’t become an elderly person with arthritis. =)

LikeLike

Harry Watson

April 8, 2013

I grew up in Scotland in the 60’s and 70’s and when I was very young I remember shop keepers would stack cans in a pyramid on the shelves behind the counter and the top can would always be stood at an impossible angle on one edge , did you ever see this done where you were ?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 11, 2013

I’ve never seen it, but I’d like to. Was it some kind of trick?

LikeLike

Harry Watson

April 11, 2013

I think it had something to do with the rim off the cans being more pronounced than they are now , but it was some sort of mysterious magic to a six year old

LikeLike

reneejohnsonwrites

April 8, 2013

I can instantly smell the foul scent of the tiny paint pots that accompanied the paint-by-number sets at your mere mention of them. And the scent of the sticky-sweet cotton candy that we got at the beach. I suppose that is magic! Nice memories!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 11, 2013

Memory itself is definitely magic, Renee. How do we store and recall sounds? I’m not sure we’ll ever crack that mystery.

LikeLike

Lady from Manila

April 9, 2013

Charles, your sentiments above didn’t surprise me much as you’ve repeatedly said you’ve got the inquisitive mind and attention span of a boy. I’ve realized as well long ago that expectations could only lead to disenchantment. Just the same, our human nature could only crave for the newest, the latest, and what apparently seems more exciting. One more truth – the magic of anything man-made is evanescent. People, including me, have yet to learn the lessons.

I’m afraid of losing the wonders of life I’ve been holding onto all my life. Hopefully, my simple mind will sustain me in finding joy in nature and what’s real. True friendships included.

I’ve been missing you, my dear pal. I hope you’re doing fine.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 12, 2013

I think that as long as you worry about losing that wonder for life, there’s less chance you’ll actually lose it.

I hope you’re doing fine, too.

LikeLike

She's a Maineiac

April 9, 2013

I think if we really discovered how cotton candy was made, we’d stumble onto the meaning behind the universe.

This post made me giggle because I remember vividly last summer you pointing to your wife’s cell phone and whispering, “How in the world does the sound from her voice travel up to the phone when it’s way up near her ear?” I’m constantly in awe of things like phones, that our voices can travel across wires. I’m especially blown away by TV in general. My son and I were discussing how bizarre it is that we can sit in our living room and view other people, their images and hear their voices on a little box. It’s really spooky.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 12, 2013

And how do those voices travel through wires and not get completely garbled along the way? I always wonder how someone from the 1700s would react if they could see television or a computer. I think they would be terrified.

LikeLike

winsomebella

April 10, 2013

We complain a lot about air travel—-but hey, we’re flying!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 12, 2013

Stacia, I’m still stunned every time I see a commercial jet get off the ground and climb into the sky. It just doesn’t seem possible. And I complain, too.

LikeLike

Chichina

April 10, 2013

I figured the name in your email would lead me to your blog………………….I love what I’ve read so far.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 12, 2013

It was great to see you here. And I’m enjoying your blog, too.

http://risingsun1blog.wordpress.com

LikeLike

aunaqui

April 16, 2013

THE SPOON-TAPPING MAGIC PART IS SO RELATABLE! My mom always did that, too.. and it always, always worked. Great post, I love your thoughts.

Aun

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 17, 2013

I just came from your blog, Rose. I’m glad we’re back in touch.

LikeLike

aunaqui

April 18, 2013

Me too! 🙂 I’ve missed writing and keeping up with your blog.. your posts are ALWAYS amusing, relevant and inspiring. Writing seems to come in seasons for me. I’m usually a pretty consistent reader, but after I read through the entire Harry Potter series for the first time two months ago (in record time: it took me just a little over a month!), I went into a sort of literary-depression. Silly, I know, but I’m definitely back — back to reading, and back to writing (for my blog and my novel – I’ve taken a very long break from the latter, but I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing).

🙂 Your fan and friend, Rose

LikeLike

Rufina

June 29, 2013

Oh my! I have some blog catching up to do! I am looking forward to a two and a half week cottage vacation north of Toronto, where I will do just that. I wonder if I can find a summer fair nearby for cotton candy (which for me must be pink, not blue or green or yellow)…I know that there really is magic everywhere, but a summer fair seems a fun place to remember how easy it is to find it.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 29, 2013

Two and a half weeks in a cottage sounds pretty magical to me. Have a great time. As far as catching up on blogs, I don’t think it’s possible.

LikeLike

veenusingh

October 2, 2013

Nice 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 3, 2013

Thanks!

LikeLike

Anna

October 8, 2014

It is all, because we are being realistic.. Start losing your religion, and the magic is gone. Lose your friends and family and the magic is gone. In this world there is no magic. Only when you close your eyes, thats when the magic starts.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 10, 2014

I don’t know, Anna. I stood at the base of a waterfall the other day, and it was pretty magical.

LikeLike