I live in one of those places where tourism is a significant part of the economy. At this very moment, people all over the world are booking flights and reserving hotel rooms so they can devote a fraction of their summer to experiencing life in this exotic location.

I live in one of those places where tourism is a significant part of the economy. At this very moment, people all over the world are booking flights and reserving hotel rooms so they can devote a fraction of their summer to experiencing life in this exotic location.

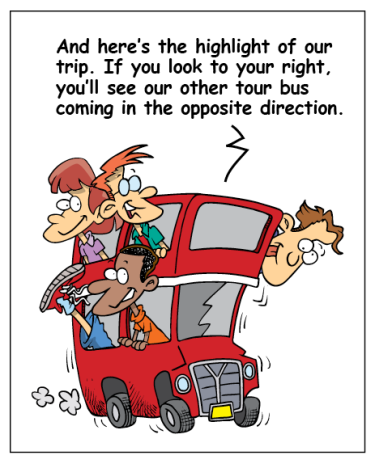

Not that this location is all that exotic. There are no snow-capped mountains, palm trees, ancient temples, or howler monkeys. Grilled cheese and tapioca are considered spicy foods. And one of the downtown bus tours slows almost to a stop so visitors can catch a glimpse of the indoor parking garage. “It was the first such facility to be built in the city, has hourly and monthly rates, and includes space for more than three hundred vehicles.” Many of the tourists crane their necks for a better view. Some take pictures.

The lesson, I suppose, is that the motivation to travel isn’t so much about what’s here. It’s really about getting away from there – the neighbors, the dog, those annoying commercials on the radio, that front-page story about upcoming pot-hole repairs – anything that’s familiar, and therefore uninteresting. We seek out what’s different and exciting.

But sometimes those things that are different and exciting can create problems. Local customs can be especially confusing.

Tipping, for example.

In Japan, and probably in other countries, it’s considered disrespectful to offer someone money beyond their regular fee for a service they’ve provided. It suggests to them that you believe they made a mistake on your bill, or that you think they don’t earn enough. Meanwhile, in North America, failing to leave a tip means that either you were extremely dissatisfied or you’re a complete jerk. But even here, tipping is appropriate in only certain situations.

When I was little, my father would take me to the barbershop, and after paying for my haircut, he would hand me a couple of quarters. I would take them over to the barber, who by then was already starting on his next customer. I’d tap him on the leg and he’d look down, pretending to be surprised at this unimagined gesture of generosity. Managing for a moment to ignore the thousands of tiny spears pinching my neck, as well as the useless powder he’d brushed over them, I’d find myself looking forward to my next haircut, when the barber would welcome me back as a most treasured customer who, all those weeks ago, had presented him with the riches of loose change.

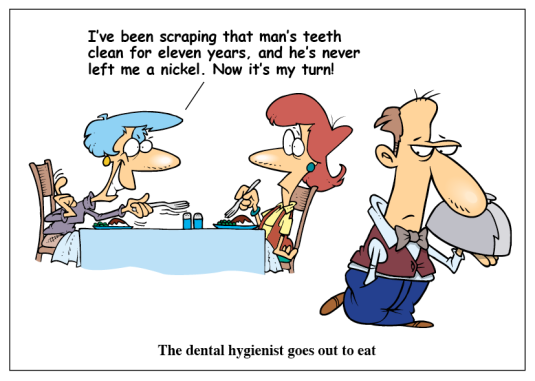

On some other Saturday morning, we’d go to the dentist’s office, a place of creaky floors and reluctant footsteps. Like the barbershop, it had an adjustable chair padded with cracked vinyl. Quiet, unidentifiable music seeped in from somewhere. The predominant sound came from a drill instead of clippers, and the sharp instruments produced a discomfort unlike anything a comb or scissors ever did. In my mind, though, the two had a common element in that they both aroused in me the wish that I could be almost anywhere else but there. And so it was easy for me to notice that at the end of the appointment, we never seemed to give the dentist any money. Thus began my education about tipping.

During the Mass in church, men would come around with long-handled baskets and we’d all drop small envelopes into them. The envelopes were pale pink, green, or yellow, and inside we’d tucked seventy-five cents, or maybe a dollar bill. I thought we were giving God a tip, although I couldn’t imagine why.

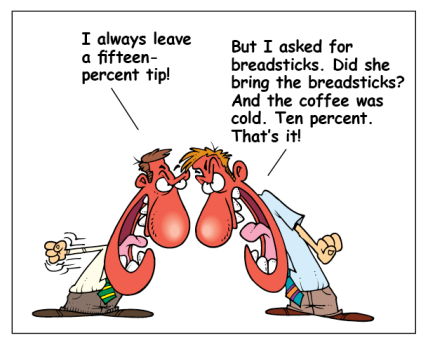

As we got up from our table at a restaurant, I’d listen while the adults discussed what to leave for the waitress. After a meal filled with disagreements, this was always the loudest and the most animated.

At baseball games, my father would slip the usher some money for helping us find our seats and wiping them off with a filthy rag, even though the tickets had the seat numbers printed right on them, and we’d spend the next few hours breathing in cigar smoke and getting covered with peanut shells and splashed beer.

The strangest part was that many of these people were expecting a tip. Yet for some reason, the butcher and the grocery store cashier assumed no such thing. Neither did the man who drove his truck down our street, selling fresh fruits and vegetables. Or plumbers, or firemen, or the nurse who stitched up my finger after it was pinned in a slamming car door.

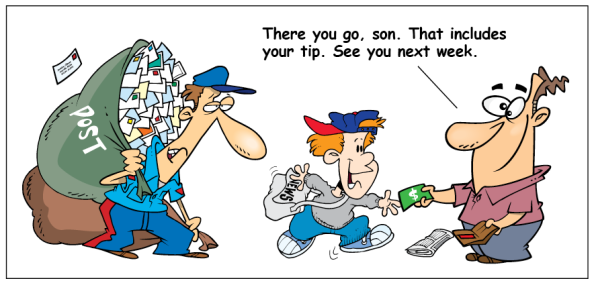

The mailman received a nice gift around Christmas each year, but so did the newspaper boy, who also got a tip every single week. We never got a telegram, but if we had, we’d be expected to show our gratitude with cash. Heaviest of all, the new telephone books showed up mysteriously, deposited at our front door in the middle of the night by invisible ghosts who apparently worked for free. When I got older, I’d occasionally go to some fancy place where they parked your car, hung up your coat, and handed you a towel in the bathroom. Office buildings had a person who sat on a stool in the corner of the elevator and pushed the buttons for you. The guy at the car wash always finished up by wiping down the driver-side arm rest, a convenient and conspicuous spot to be standing when the happy owner of the sparkling vehicle got in.

When I got older, I’d occasionally go to some fancy place where they parked your car, hung up your coat, and handed you a towel in the bathroom. Office buildings had a person who sat on a stool in the corner of the elevator and pushed the buttons for you. The guy at the car wash always finished up by wiping down the driver-side arm rest, a convenient and conspicuous spot to be standing when the happy owner of the sparkling vehicle got in.

But contradictions persist.

We tip the taxi driver, but not the train conductor. The chauffeur, but not the airline pilot. We tip for pizza delivery, but not for heavy furniture or heating fuel. We tip the person who cleans our motel room, but not the lifeguard at the beach. The babysitter, but not the teacher. The bartender, but not the pharmacist.

What’s the general rule, then? Is there a grand unified theory of tipping? I’ve managed to do little more than narrow it down:

We pay extra for food that’s cooked, rather than raw. (The exception would be a sushi bar, although not a sushi bar in Japan.) We pay extra for cosmetic enhancements, but not for medical services – shoe shines and manicures, but not eye exams or lung transplants. We pay extra when someone does something we could have just as easily done ourselves, like opening a door or carrying a suitcase, but not when someone has gone to school for eight more years to learn skills we will never have, like installing circuit breakers or neutering the cat. We pay extra for things we really want, such as flowers or a massage, but not for things we buy because we have to, like insurance or dry cleaning.

If I had to pin it down, I’d say the pattern is that we tip for luxuries, but not necessities. When we believe we’re treating ourselves in a special way, we also feel compelled to share our good fortune. Maybe that’s all there is to it.

The truth is, I don’t understand tipping any more now than I did after my first trip to the dentist. So if you’re one of those tourists headed this way, I have just one piece of advice. Take the downtown bus tour and give the guide a few dollars at the end of the ride. But if you use our world-famous indoor parking garage, there’s no need to tip the lady in the booth. I’m almost sure about that.

The Cutter

March 6, 2013

I get confused by when to tip as well. Nowadays, I usually just consult the internet. Of course, being the internet, there’s usually a lot of contradictory information.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 6, 2013

Back when gasoline was thirty cents a gallon, I used to tip the people who pumped the gas, especially if they also cleaned the windshield. I can’t remember the last time that happened.

LikeLike

Marie M

March 7, 2013

I can’t remember when gasoline was thirty cents a gallon. Are you sure we’re the same age?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 7, 2013

I underestimated a little — it was thirty-six cents a gallon. See:

http://www1.eere.energy.gov/vehiclesandfuels/facts/m/2012_fotw741.html

And, no, you’re older.

LikeLike

shoreacres

March 6, 2013

When I was a kid, my mom sometimes would ask my dad, “Are you going to leave a tip?” He’d say, “Buy high, sell low”. Then, he’d reach for his wallet.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 6, 2013

That’s my financial slogan, too. I developed it over years of buying and selling cars at a tremendous loss. If I ever had enough money to get involved in the stock market, I’d probably cause another crash.

LikeLike

morristownmemos by Ronnie Hammer

March 6, 2013

The way to tell is to offer a tip. If the recipient looks surprised you know it was not expected. If he takes it matter of factly you did the right thing. If he takes it and scowls, you know you under-tipped. If he clicks his heels and does a happy dance you may have over tipped.

Does that make it easier for you?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 6, 2013

Canada uses one-dollar and two-dollar coins. Giving someone a coin or two always feels inadequate, I guess because a folded bill could at least look like more than it is.

Thanks for the help, Ronnie.

LikeLike

bitchontheblog

March 6, 2013

Charles, if I tipped you for every time you make me laugh, giving me such pleasure reading your prose you’d be rich and I’d be begging on the streets to keep the coffer filled.

U

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 7, 2013

No need for tips, Ursula. A comment like that is priceless. Thank you.

LikeLike

Stacie Chadwick

March 6, 2013

If you’ve ever waited tables (and every man, woman and child should…but only after a certain age because of annoying things like labor laws), you’ll find yourself tipping any and everyone who’s willing to take your money. I agree with your witty essay, the when to tip/when not to tip makes practically no sense. I still can’t figure out why no one in my family tips me. Being a laundress/cleaner/chauffeur/food sanitation expert is a tough job.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 7, 2013

I’ve never waited tables, Stacie, but both of my daughters have. Some of their stories made me wish I’d been sitting in the restaurant when certain customers were there. I was continually shocked to hear how rude, demanding, and abusive people can be. But at least our families always appreciate what we do. They do, don’t they?

LikeLike

Stacie Chadwick

March 7, 2013

Here’s to hoping. =)

LikeLike

foodsnob86

March 8, 2013

I think having good manners is just as important as good tips. You can make that person’s day by being an easy, polite customer.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 10, 2013

It sounds as though you speak from experience.

LikeLike

Diane Henders

March 6, 2013

You’re brilliant, Charles. Tipping for luxuries but not necessities is the closest thing to logic I’ve ever seen applied to the whole tipping process. I’ll never understand it. I think the Japanese have the right idea.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 7, 2013

Why don’t we tip flight attendants?

I think it’s flow chart time again, Diane.

LikeLike

Cathleen Barnhart

March 6, 2013

Once, long ago, I tried to tip the steward on an airplane after he served me my little plastic cup of soda. I figured that he was providing a service akin to a waiter. He was actually surprised and I think more than a little miffed, and refused my tip. He told me he was a professional, so a tip wasn’t necessary. But what would that make waiters and waitresses? Unprofessional? It’s a puzzle.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 7, 2013

I just brought up this same question in response to the previous comment. That has to be one of the most maddening jobs around — pushing those bulky carts up and down those narrow aisles, dealing with cranky passengers. I’d last about three days.

Where the heck have you been? Are you blogging again, I hope?

LikeLike

thepolkadotskirt

March 6, 2013

As a former waitress and bartender I consider tipping a must. However, if we paid folks a living wage, it would be so much easier! Great story as always.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 7, 2013

Why don’t restaurants put up signs that explain to customers why tipping is important? Some probably don’t realize that servers are being paid less than minimum wage. The people I don’t understand are the ones who go out to eat, then fail to leave a tip because they can’t afford it. And then there are those who leave without even paying for their meals — and the restaurants that punish the servers for it.

LikeLike

"HE WHO"

March 6, 2013

The duality (if we can call it that) of “tipping” you point out is something I’m sure George Carlin missed altogether but could have attacked with a vengeance. Personally, I am glad we don’t have to tip grocers or dentists, etc. Perhaps groceries are considered “take out”. I don’t know how the medical profession missed out, but it’s a good thing. I can’t afford them now!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 7, 2013

You’re right, HW: Pay scale is another factor. When doctors and lawyers start tacking on a fifteen-percent gratuity, we’ll be in big trouble.

LikeLike

Patti Kuche

March 6, 2013

Tipping at the hairdresser is a nightmare when I always think the cost is expensive enough. How much do I tip the person who washes my hair compared to that expected for cutting, styling etc etc? My hair is now much longer than it needs to be simply due to the trauma of the tipping calculation, compounded by the fact that I never seem to go back to the same place, because I feel marked and mocked at my poor (I think generous) tipping . . . .

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 7, 2013

Why can’t it be done anonymously? They could have a box set up at the front and you could drop the tip into that on your way out, along with comments about the service. And then at the end of the day, the owner or manager would divide up the tips in some appropriate way. Wouldn’t that be less awkward?

LikeLike

Tammy

March 6, 2013

I want to know where the 15% idea came from. Does that only apply at restaurants? So confusing!

Thank you for another great post!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 7, 2013

It probably started at a time when fifteen percent of the cost of a meal was about ten cents. What really confuses me is that in restaurants that charge exorbitant prices for mediocre food, you’re still expected to tip at the same rate. And if you order a glass of wine, that also drives up the tip, while a glass of water — which requires the same effort — adds nothing.

LikeLike

Sarah

March 6, 2013

Hmm, Charles. I’m suspicious that you know so much about the guided tour of your local parking garage. Anything you want to admit? Are you perhaps moonlighting as a tour guide? Or maybe, just for kicks on a rainy day, y’all pretended to be tourists yourselves and did touristy things?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 6, 2013

I do some freelance writing for the local tourism board, so taking the tour a few years ago seemed like a good idea.

LikeLike

The Retiring Sort

March 6, 2013

A clever and entertaining post!! Thanks for the smiles, and the education!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 6, 2013

Thank you, TRS. I appreciate the feedback.

LikeLike

subodai213

March 6, 2013

Sad to say, some states allow it, and some restaurant chains (can you spell Applebee’s?) only pay $3.50 an hour to their servers. The rest of a ”’liveable wage” is expected to come from the customer in the form of a tip, the same customer, who has already paid a lot for a meal. Quite literally, the customer pays the employee.

This is bull—- but it’s how Rich Americans get rich and stay rich…by making the poor schmuck who works in his restaurant work for wages that are on par with that of the Chinese. That has become the Rich’s target, and they’ve reached it: if you aren’t willing to work for the same wage as the lowest paid worker in China, then, go somewhere else……..they can always find someone who will work for it.

Point being, I always tip in restaurants. The servers work very hard for what little they earn. Besides, if you get a reputation for being a good tipper, they take care of you.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 6, 2013

I’ve never been able to understand how restaurants get away with paying less than the minimum wage. Doesn’t minimum mean minimum?

LikeLike

Stacie Chadwick

March 6, 2013

Did this, by chance, prompt your post?

http://shine.yahoo.com/work-money/what-kind-of-person-tips-10-dollars-for-85-pizzas–173851199.html

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 6, 2013

It looks like the Yahoo post was published four hours ago — so mid-afternoon. Mine went up this morning. They seem to have a few more comments, though.

LikeLike

Stacie Chadwick

March 7, 2013

Good timing for tags!

LikeLike

Betty Londergan

March 6, 2013

I pretty much hate tipping in all its forms. I’d much rather just pay an extra mandatory $2-10 and be done with it … tipping feels like blackmail to me. Particularly when you get your hair done by the guy who owns the salon … and then have to tip him on TOP of the service fee? Please. I was a waitress for years so I always tip generously — but when I’m at a spa (oh so sadly infrequently) or getting a coffee, I feel like it’s idiotic to pay a 50% markup to reward the person to pour my $2.50 black coffee. But .. I do. I just comply rather than make anybody feel badly. But still — I resent it. Great thoughtful post!!

LikeLike

Vikki Sorensen

March 6, 2013

I so agree with Betty! I was a waitress also so I do tip generously. However, when I go to McDonald’s, I’m not expected to tip. Yet, at my local Starbucks, there’s a tip jar not only in front of the register but outside at the drive-up window. Subway has also started a tip jar yet my local Culvers doesn’t. So, I guess, if the quality seems better, I should pay for it AND leave a tip???? Confusing!!!!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 7, 2013

Vikki, I wonder if some of those places put their own money into the tip jar, just to get things started and make customers feel like cheapskates if they don’t add to it.

LikeLike

Vikki Sorensen

March 7, 2013

Could be however, as no real service is being presented, I don’t often feel obliged to tip.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 7, 2013

I’ve had the same thought when it’s the owner. If the idea of tipping is to make up for a meager salary, how does that apply to the person who’s taking home all the profits? Although I’d no doubt think differently if I were in the owner’s position. Some businesses are barely hanging on.

Thanks, Betty. It’s good to hear from you. I hope all is well.

LikeLike

Elyse

March 6, 2013

Just tonight as we paid the tow-truck driver to pull our son’s car out of the mud, we wondered how much was an appropriate tip for a tow truck driver/puller-outer. Then he charged 45% more than what he said he’d charge at the beginning.

Towing is hereby not a luxury.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 8, 2013

So he gave himself a 45 percent tip. Nice.

LikeLike

lostnchina

March 6, 2013

I think this is the second time in 3 months you’ve mentioned your hair, getting a haircut, and how getting a haircut bothers you, Charles. Maybe there’s some (not so) deep-seeded anxiety about that…and tipping?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 8, 2013

Not so deep-seated at all, Susan. Getting a haircut was one of those repetitive and slightly stressful events — like going to confession and visiting my godparents. They’ve all burned themselves into my memory, so that associated thoughts, feelings, and details crowd my brain and prevent me from remembering the movie I watched last night.

LikeLike

AIT's Fresh Beginning

March 7, 2013

Eternal dilemma!

Many restaurants here charge a mandatory ‘Service Charge’ apart from the Service Tax, Value Added Tax, Education Cess, etc, etc. The logic behind it, I am told, is that it is a pool of tips to be divided amongst all staff members (including the ones who work unseen – the chefs, assistants, cleaners n the like) at the end of the workday.

Sometimes, when the service exceeds our expectations, we additionally tip our waiter (with cash in hand, sneakily); as direct tipping is against the policy in places that bill a service charge.

I like your sneaking in some deep too….anything that’s familiar, and therefore uninteresting. We seek out what’s different and exciting.

Hello Charles 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 8, 2013

Restaurants in Italy do the same thing by adding a cover charge to the bill. Americans going there for the first time often fail to notice this and add on another fifteen percent (or more) for a tip. I speak from experience.

It’s great to hear from you, AIT. Your new blog looks great.

http://beginningafresh.wordpress.com

LikeLike

Sandra Parsons

March 7, 2013

Following your explanation I have finally found out why I hate tipping: I hate luxury. What, I am completely capable of lifting my own bag into the boot of your cab, thank you very much. Actually, I am completely capable of using public transport instead of a taxi. But I do understand that some people in “tippable” jobs hardly make a living on their basic salary. Which obviously isn’t quite true for the dentist, so maybe here’s your distinction criterion?

Brilliant title by the way, as always, Charles.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 8, 2013

I guess when it comes to transportation, the people who carry a small number of passengers (taxi and limo drivers), expect tips. Airline pilots, train conductors, and bus drivers are hauling around dozens or hundreds of passengers, so tipping — while lucrative — would take too much time. And, yes, salary is also a criterion. I’m having an EKG done today, and probably won’t tip the technician.

And thank you for being so encouraging, as always, Sandra.

LikeLike

winsomebella

March 7, 2013

Luxury is somewhat in the eye of the beholder and therefore drives the debate as to the accurate tipping point :-).

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 8, 2013

That’s true, Stacia. Some things are clearly on one side of the line or the other. But the line itself can be fuzzy.

LikeLike

dearosie

March 7, 2013

trying to leave a message on a computer without my WP password is almost as difficult as climbing the Andes.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 8, 2013

I’ve been having similar trouble, Rosie. I have to log in over and over when leaving comments, and even when replying to comments on my own blog.

LikeLike

laughatmypain

March 7, 2013

Great site! Part of my blog is also comedy, but with serious subjects too (latest one is just a review of survey sites, but that’s just a one time post. Also stuff about living with Aspergers). I’m following your site now and check me out at http://laughatmypain.wordpress.com/ (shameless plug!)

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 8, 2013

Thanks for subscribing, and for the kind words. Good luck with the new blog.

LikeLike

dearosie

March 7, 2013

ah hah I did it!

Great post Charles! Its me rosie… I lost my comment…

I saw a program on PBS that explained the sad story that restaurant workers who stand all day preparing delicious meals for us cannot afford to feed their own families.

Shame on us that we allow the owners of restaurants to pay their workers $2 or $3 per hour and if we don’t tip generously they go hungry!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 9, 2013

Given the right setting and circumstances — a busy, high-priced restaurant — a server could earn a wage that’s many times what the average worker makes in most other industries. But using that possibility to justify underpaying all servers is wrong.

LikeLike

Barbara Rodgers

March 7, 2013

Ah yes, the mysteries of tipping etiquette – you were an observant little kid to notice that not all services received on an adjustable chair padded with cracked vinyl called for a tip.

Only once in our lives did we require the services of professional piano movers, to transport my great-grandmother’s baby grand piano 150 miles to keep here for our daughter. After the movers installed it in our home they kept hanging around after we had paid the thousand dollar bill. It was only days later that it occurred to us that they might have been expecting a tip…

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 9, 2013

Why didn’t you call me? I would’ve done it for nine hundred.

LikeLike

Allan Douglas (@AllanDouglasDgn)

March 7, 2013

This is hilarious and enlightening. While reading it I was reminded of a movie I saw – don’t remember the title exactly; Blue something – Steve Martin played a New York gangster in the witness protection program who is sent to some burg-town to hide. He tries to tip the cashier at the grocery store and has the place in a furor before it’s all over with. What an odd society we live in…

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 9, 2013

And getting odder all the time, Allan. I’m starting to feel guilty that I never tipped the lunch ladies in my high school cafeteria.

LikeLike

nailingjellotoatree

March 7, 2013

The other stressful tip time is when you get to the airport, check your suitcase at the curb and the man says, “I checked your bag all the way through to your destination, so you won’t have to carry it anywhere.” AND then he repeats it. Oops, he’s trying to ask for a tip (In my mind, for doing his job) Shoot. Didn’t plan for that comment, Don’t have anything smaller than a $20 and I need that! At that moment I “get busy with the kids” and try to nod absently and shuffle off pretending I didn’t understand. Seems like everyone is expecting tips now. Our local mall food court has tip jars at the front counter….I’m getting old and not cool with that.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 9, 2013

It would never occur to me to tip the guy at the airport. But then, air travel these days does little to put me in the tipping mood.

LikeLike

nailingjellotoatree

March 13, 2013

Well unfortunately it never occurs to me in advance so that I can plan accordingly. And usually by the time I’ve gotten myself, 3 kiddos and 6 suitcases to the curb at the airport, I’m just ready for the curb check guy to do what the curb check guy does. And, thankfully, I have 3 young’uns I can get distracted by and pretend I didn’t hear him asking for his tip.

Sorry curb check guy, gave my last dollar to the airport shuttle bus driver who I definitely knew would be standing there holding their hand out! Oh and BTW, the airport shuttle driver at least lifted all 300 lbs. of luggage twice, double what I can say for you since I loaded them on your cart and pushed them to your conveyor belt and you slapped a tag on them.

Sorry for the rant!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 16, 2013

It’s okay. Just thinking about my last few airport experiences makes me want to rant.

LikeLike

Val

March 7, 2013

Food for thought here, Charles. Growing up in England as I did, tipping was regarded as a way to say thank you either to people who didn’t get a good wage or who were following in a tradition of some sort. Of course, later that deviated in England as it has in North America and elsewhere. Times change. Personally I think it should be done away with altogether and people should be paid what they need to live. But then I suspect that even tipping with money were made illegal, then there would be some other version of it.

You mentioned that dentists don’t get tips, but in fact I wonder if this is true? For instance, as a doctor’s daughter I know that doctors do get ‘tips’ but just not in the form of money. Some of their patients thank them beyond the wages they earn, with gifts of food, for instance.

Where I used to live in London, there were always the ‘Christmas boxes’ as they were called, for various people and most particularly the dustmen (trash collectors). Latterly I think we stopped giving money and instead gave them a pack of beer instead! (And hoped they didn’t drink and drive or the mess would have been worse than usual!)

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 9, 2013

I suppose part of the reasoning behind the emphasis on tips rather than a decent wage was that it would motivate servers to work harder for their customers. The flaw in that logic, of course, is that it presumes those customers will respond fairly, and they often don’t.

Do you think patients in Britain are still giving gifts to their doctors? I’ve never heard of anyone doing that on this side of the Atlantic.

LikeLike

Val

March 9, 2013

Yes, almost certainly. I’d think that it’s more common in rural areas – farm produce, for instance – but yes, there will always be people here who do it. Whether the doctors these days accept gifts gratefully or impose some sort of rules on their patients, I don’t know. I do know that it was a nice gesture and made the patients feel good.

LikeLike

Rufina

March 7, 2013

And tipping in a smalltown vs. tipping in a big city is also a point of disparity!

Service is service no matter where you are, good or bad. But yet, it’s related to the overall price of the original bill, and we are expected to tip accordingly. I waitressed for many years, in different venues from coffeeshops to fine dining restaurants. Those tips helped put me through school, so I of course am happy to tip wherever I go, when it’s warranted. I do agree though, it can all still be a bit mystifying.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 9, 2013

It is baffling. A waiter or waitress working in a slow-paced expensive restaurant could make a lot more money than someone who’s running themselves ragged in a diner or coffee shop.

LikeLike

Margo Karolyi

March 7, 2013

I wrote a post a while back (http://theothersideof55.wordpress.com/2011/05/29/does-tipping-insure-promptitude/) that covered the history of tipping and asked some of the same questions you’ve posed here (why do we tip for some things but not others, and who makes the rules?) I got some interesting comments back, especially from people who work as servers in the U.S., where the pay is much worse than in Canada. I guess tipping is just one of those things we’ll never fully understand.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 9, 2013

You raised several points I hadn’t thought of, Margo. The poor UPS and FedEx drivers never even entered my mind. I did wonder about librarians, but only after I’d published the post. And I was recently shocked to learn how much higher minimum wage is here in Canada compared to the minimum wage in many states in the US.

LikeLike

rangewriter

March 8, 2013

Great post, as always Charles. I’ve been in and around all sides of tipping, and yet the protocol still confuses me. I’m always stumbling into situations where I realize that other people having been tipping, while I’ve simply paid my bill and walked out the door.

So, where are these places you stay where “they parked your car, hung up your coat, and handed you a towel in the bathroom?” ;-).

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 10, 2013

There are a lot of places in New York, and in other big cities, where they have valet parking. You pull up to the door, someone takes your car and drives away, and you spend the rest of the evening hoping that guy really works there. When he brings your car back, you’re so relieved you hand him two or three dollars. There are restaurants that have a coat check booth. It’s the same thing: You leave your coat with the person and when you’re finished eating, they sell you back your coat for a couple of dollars. The first time I ever came across the bathroom guy was at an expensive hotel, where I was attending a meeting. You wash your hands and he gives you a paper towel, and you’re supposed to tip him. I’ve always wondered who thought that was a necessary service.

LikeLike

rangewriter

March 11, 2013

Hah! I thought you meant all three in one! I’ve experienced all three individually. The toilet tipping is quite common in Europe. The results are nice. Always nice clean bathrooms with plenty of tp.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 11, 2013

I’ve experienced all three at a few weddings on Long Island. I’m trying to remember if, after all that tipping, I had enough left for a wedding gift.

LikeLike

writingfeemail

March 8, 2013

I believe in tipping well, but secretly wish that everyone would just be paid enough so that it wouldn’t be necessary.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 10, 2013

It would be much nicer if it felt as though tipping were a voluntary gesture.

LikeLike

marymtf

March 8, 2013

To tip or not to tip, I used to find it confusing. Still, do, but I’ve decided that tipping should be linked to badly paid jobs. It seems to me that the harder you work the less appreciated you are for it. Servers and taxi drivers get a tip from me. They need the extra dosh; dentists do not, I imagine that train conductors would appreciate a tip but unlike the waiter and taxi driver conductors wouldn’t need to count on the tips to survive. You make even the humblest topics interesting, Charles. 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 10, 2013

Could you imagine not tipping this guy?

LikeLike

marymtf

March 10, 2013

He’s a taxi driver type person minus the horse power, so of course he’d get a tip. Proves my point, doesn’t it? People who do the slog work get paid the least.

LikeLike

Dawn Whitehand

March 8, 2013

We don’t tip for anything in Australia… and that’s because we have a strong union movement and therefore reasonable minimum wages. So my understanding is that you guys tip the elevator attendant because he has poor wages, whereas the dentist is on a good income…

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 10, 2013

Actually, we tip the elevator attendant because it’s such an uncomfortably small space, and because we’re afraid if we don’t, he’s going to stop the elevator between floors.

LikeLike

Earth Ocean Sky Redux

March 9, 2013

I’m an over-tipper and I tip just about everywhere – a couple of exceptions: I give a Christmas bonus to the UPS man rather than a tip for each trip and a Christmas bonus to the hairdresser (who owns the salon) also rather than a weekly tip. But like many of you, I stop short at Starbucks. I’m not sure why other than I never quite feel they’ve earned the tip. I’m the most generous to cabbies and small restaurant waitresses. Bottom line, I figure if I am being served, pretty much no matter the situation, someone is doing something nice for me and in my book, that deserves a tip.

However, I am not consistent about leaving a tip in a hotel room for the housekeeper. I’m never quite sure about that.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 10, 2013

The hotel room situation is a dilemma, EOS. If you’re there for an entire week and leave a tip on the last day, how do you know the person getting it is the same person who’s been taking care of your room the whole time?

LikeLike

Worrywart

March 9, 2013

Great post! We just returned from Japan and Southeast Asia. The fact that Japan is possibly the most expensive place in the world, may qualify it as a “luxury,” hence, proving your theory. I have to say, not tipping was great. The weirdest tipping we saw was in Indonesia. Drivers tipped people (seemingly ordinary, random people who were just standing in the middle of the street – one was a young boy) for stopping traffic so they could go through an intersection. Since there are no traffic lights (or traffic laws as far as I could tell), crossing the street in Indonesia also qualifies as a luxury, so I think your theory holds up!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 11, 2013

I hope you had a great trip, WW. Will you be blogging about it?

LikeLike

earthriderjudyberman

March 9, 2013

I don’t mind tipping for good service, but I’m appalled that restaurants pay their staff less because they expect their customers to provide a tip. When my daughters were teens, they worked at a restaurant where customers typically did not leave a tip. So much for a living wage.

In France, we had a hard time figuring out when, where and what to tip. (Sometimes, you weren’t supposed to as the tip was included in the bill.) You’re right, Charles. It’s very confusing.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 11, 2013

Judy, I don’t understand the economics of the restaurant business, but one factor must be its unpredictability. I guess by paying lower wages and relying on tips, the owners protect themselves against having to pay their staff to stand around waiting for customers to show up. That arrangement works, as long as people remember to leave a tip. But as you said, many don’t.

LikeLike

Tom Marshall

March 9, 2013

Interesting questions. It all seems to swirl around in the head, and I know they have apps to help one figure out what is appropriate for a tip. I kind of like the commercial which has each person’s number above their heads–though people may not want others to know what they make–but in this case it would be a T for “tip”. Even a standard percentage sign next to it would help, though this might put the people who make apps out of business. I guess I don’t have any good tips, just questions like you.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 11, 2013

But any kind of app or chart to help you determine what’s appropriate has to be based on local customs, so it still isn’t going to make much sense. I think tipping should be instinctive: Did this person enhance the experience for me, and if so, should I thank them with some extra money? If everyone did that consistently, it would motivate the best workers to try even harder, and we’d all benefit. In theory, anyway.

LikeLike

lameadventures

March 9, 2013

Possibly another tipping “dividing line” i.e., who we tip and who we don’t tip is whether or not the worker has a job that provides health insurance. I don’t think that most service workers — cabbies, hairdressers, servers, food deliverers, etc., get it. I do agree with all of your commenters that would like to forgo tipping in favor of that person getting a better wage. Were that to happen, the proprietors would probably stick it to the consumer.

I don’t go to Starbucks very often, but that’s one place where I refuse to tip. They’re a big corporation. Seeing that tip jar there has always rubbed me wrong, right up there with the barista’s inability to properly spell my first name, Virginia, with three i’s. Seeing my name spelled “virgina” makes me feel like an orifice. Telling them to just use the abbreviation “VA” also baffles them.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 11, 2013

It seems to come down to an unconscious desire for fairness. In so many situations, the people who do the hardest work get the least reward, and most of us know how that feels. But you’re right: Offering higher wages and health insurance would mean higher prices, because even a smaller increase in profits is considered a loss these days.

Sorry to hear there are so many people who can’t seem to spell Virginia. Imagine if you’d been named Massachusetts.

LikeLike

the joker

March 10, 2013

I tried to tip our taxi driver from the airport to our hotel when we first landed in Shanghai. He was very confused and gave me back the money. Then in a restaurant, I paid, left a tip and left the place. The waitress came running after me and said I left some money on the table by mistake.

China is just like Japan with no tipping culture. At first I found it strange, now I like it – you don’t need to worry about how much to tip, or should I tip at all when service is bad, etc.

Great post!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 12, 2013

But I wonder: is it harder to get good service because of the no-tipping policy?

LikeLike

Amiable Amiable

March 11, 2013

I worked as a “chamber maid” back in the day, when I was saving for college. Tips were few and far between, even though I know people could have bounced quarters off of the beds that I made. But now I’m wondering what if they bounced my tips off the beds and out the doors? Anyway, I always leave tips for housekeeping now. And I figure they think I’ve carelessly left money behind … because nobody tips housekeeping nowadays.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 12, 2013

I have a feeling the people who clean motel rooms don’t do very well with tips. By the time they get to your room, you’ve already checked out and you’re seven exits down the highway. Sometimes, if I don’t have the cash, I’ll ask the front desk person to add something to my bill and give it to housekeeping. But I have no idea where that money ends up.

Chambermaid? Was that back in the twentieth century?

LikeLike

Amiable Amiable

March 15, 2013

I’m a lot older than I appear. (I worked at a colonial inn in New England.) And, yup, that money you add to your bill? It’s not getting to housekeeping, but I’m sure someone’s having fun with it! My “tip” to you: don’t do that anymore. Save the money for future trips!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 16, 2013

I really don’t like those situations in which there’s no way to be sure if the right person is getting the intended reward. I’ll take your advice.

LikeLike

finelighttree

March 11, 2013

A friend talked about a security guard in front of a plush shop asking to be ‘taken care of’ for letting her park in front of the shop even though it wasn’t legally a parking spot. We ‘tip’ a lot here in India for convenience. And while there is no particular rule as such for tipping waiters and waitresses, it isn’t considered too rude to not tip. And neither is it considered too ‘patronising’ to do it.

I enjoyed this post tremendously. And it was fun sharing little tidbits from my own world!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 12, 2013

But what would have happened if your friend had refused to tip the security guard? Would he have had the car ticketed or towed? And are restaurant workers paid enough to survive without tips?

By the way, I like your new blog and am glad you’ve opened it up to comments. Your recent post is excellent:

LikeLike

finelighttree

March 12, 2013

To answer your first question — he wouldn’t have done anything if she drove off without giving him anything. In a working day of n hours, he would probably find 10 people who’d oblige him. That’s a lot of money for a person of his means.

About the second question — The answer is relative. At any rate, they wouldn’t be working, if they hadn’t survived.

About opening the comments — I learn about myself every day. Can’t close channels is what I’ve learnt recently.

Thank you for the link.

LikeLike

JSD

March 11, 2013

Boy, you really give us a lot to think about…or rather, you do a lot of thinking. And now I’m thinking about the two nice young men who just today delivered a new appliance to my house. I should have tipped them…or not?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 12, 2013

I don’t know. Appliance delivery falls into that fuzzy area, doesn’t it?

LikeLike

Jred

March 11, 2013

Tipping is an art form…somehow with time it has gotten more complicated, as more people have come to expect a tip. I never know which way is up. However for exceptional service, in the hospitality industry, I make sure to tip well—I think it’s a good way to show someone that you appreciate the extra effort they put in to go above-and-beyond. There is good customer service, then there is memorable service.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 16, 2013

I agree, Jamie. What I don’t like is when someone does something for me, something I could have done — and actually wanted to do — myself, and then they expect a tip. It seems like extortion, although on a level so low that even saying it causes me to feel petty. Which is another thing I didn’t want to feel.

LikeLike

mandarin811

March 12, 2013

hmm…seems to me… To Tip or Not To Tip depends upon the level of education of the job position or paylevel (aside from grocery store). Dentist/Doctor – well educated/well paid. Waitress/Paper boy – less education(required)/much lower pay. However, I do note that this is not true in some cases as I do not tip the saleswoman at the local retail store, knowing she likely makes minimum wage.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 16, 2013

I think you’re right: pay level is the most basic criterion. But it gets pretty blurry after that. How do I know how much the oil change guy is making? Or the woman who helps me find the History section at the bookstore? I know the doctor is making a lot of money. But what about the receptionist?

LikeLike

Michelle Gillies

March 12, 2013

It seems to me the people who receive tips are the ones who make a minimum wage based on the fact that they will be able to supplement their income with tips. Who made up the original rules is anybody’s guess. The only time I question tipping is when it is a self service situation. You place your order, you serve yourself your food and you are expected to tip just as much as you would to wait staff that is there at your beck and call with what ever your heart desires. There is some confusion there for me.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 16, 2013

I always wonder about the people who clean tables at those all-you-can-eat buffet places. They’re working hard, and I bet they rarely get tips.

LikeLike

She's a Maineiac

March 12, 2013

People love eating out with me–I can figure out a 15% tip in seconds. Still, figuring out who to tip is confusing. I’ve never been a waitress, but I often feel it’s one of the toughest jobs, so I always tip them too much. As for my own jobs, the one that sticks out in my mind as the best tip I’ve ever received was this little old lady who’d tip me every Friday on my paper route. She’d leave me one dollar AND a Snickers bar. Can’t beat that.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 16, 2013

Waiting tables must be grueling work, Darla. You have to run around, carry stuff, and think, too. I can usually do only one of those things at a time.

A dollar and a Snickers bar. That about covers it.

LikeLike

zoetic * epics

March 13, 2013

Thanks for the tips, Charles! It’s even more confusing in England! You can go to the same bar and supposedly you need to tip for certain things but not everything. Plus, at times, we are having issues understanding their “English”. Do we have to tip them if we don’t understand what they are saying? 😉

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 16, 2013

The cultural differences do complicate things. And then there’s that language barrier. Good luck!

LikeLike

Bruce

March 15, 2013

Tipping happens in Australia as well, although I think it is on different basis than in Canada or the U.S. etc. Fortunately we have a pretty good industrial relations system in Aus. which mostly insures all employees have a minimum wage and employers actually have to pay it. Employers who do not pay according to the rules can and are, taken to court over it.

I have a hard time with the concept of a tip being expected, taken for granted. Assuming service I received from a correctly paid worker was above and beyond the call of duty, I think a tip would be fine but not an obligation.

The expectation of a tip to ensure correct wages to the employee is basically flawed for so many reasons.On a commercial level, the country’s gov’t, or system, is failing to ensure anything near a level playing field in which a business competes with others.

I rate the expectation of a tip as moral blackmail. It reminds me of being a pimply faced teenager taking out my girlfriend for dinner at a restaurant; one of those big events in your early life. When you are enjoying yourself and managed to get past the prices on the menu, around comes a photographer and then a bloody rose seller. That just about tears it; you start to feel like a real cheapskate just when things were going so well. When you get up to go, the next hurdle; to tip or not to tip.

Travel agents here provide advice on how to budget your expenses to include the ‘obligatory tipping’. Adding 10-15% to a holiday budget is not a small thing.

A doctor who saves your life in emergency ward probably doesn’t need money in the form of a tip. But he/she sure deserve one. A gov’t employee can’t be tipped because that is a bribe.

A real can of worms Charles.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 16, 2013

It would be interesting to find out how this tradition got started in the restaurant business. I understand there are slow and busy times, but that’s true in almost every industry. To have an employee relying on the generosity of customers for a decent wage doesn’t seem fair, or very realistic. And I speak from experience: both of our daughters have worked as waitresses, and it can be brutal.

Thanks for the comment, Bruce.

LikeLike

Bruce

March 16, 2013

I worked for many years in industrial relations Charles. I would be leaning towards brutal on pretend restaurant owners who put their employees and their customers in the position of being the ones who make the business work.

LikeLike

yogaofpoetry

April 3, 2013

As an American waiting tables in England, I think the tipping culture has missed the boat here. Funny, even though it’s hardly in the pub culture to tip, most servers here are at the ‘tipping’ point of flipping out (the lack of tip always comes up). I do feel it’s nice, and customary to tip for ‘good’ service (especially if you can clearly afford a ‘quid’ or two extra), something rather than nothing is best.

People who don’t have any change etc. who verbally express their thanks, are greatly appreciated, and those who can afford to tip, who eat out often, and don’t tip – are forgetting that servers not only get paid minimum wage to serve you, but, despite how they may be treated, follow up personal food requests, clean up after children, as well as a number of things that can be easily forgiven if the tips they earn can pay for their own lunch.

I’ve never been a huge tipper, but I always give something. Good discussion.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 5, 2013

I’ve always been a pretty good tipper, but after seeing what my daughters endured as waitresses, I’ve become even better. That’s a tough job.

LikeLike

gluecklichdownunder

April 4, 2013

Tipping is a weird thing. In Germany the taxi drivers get cranky with you if you don’t tip them and in Australia, they get offended.

Thanks for the post!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 5, 2013

That’s just one reason it’s always a good idea to read a travel guide before venturing into another country.

Thank you for the comment.

LikeLike

Wyrd Smythe

April 6, 2013

One way I’ve heard it is that you don’t tip professionals, career people or business owners, but your own examples show how that doesn’t work (a barber being a good example of a professional career business owner).

I like the idea of factoring number of years experience, but that damned barber is still an exception.

It’s just another one of those life minefields, I guess.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

April 7, 2013

Now I’m wondering if each culture has its own rules for tipping. Maybe the waiters in Japan don’t want your lousy tips, but the cab drivers there feel differently. Mine fields is right: it’s too complicated.

LikeLike

Wyrd Smythe

April 7, 2013

As an aside, wait persons near my corporate HQ have a little joke: What’s the difference between a canoe and people who work for The Company?

Canoes tip.

LikeLike

gina4star

May 31, 2013

This is so true! Tipping and knowing when to do it stresses me out. I’m from the UK where tipping isn’t really a thing-we’re not known for being tippers and generally (as I know it) we tip when the service (usually waiting) has been exceptional. Generally there is no expectation. It’s weird for me when I go to America and am expected to tip for everything. I live in Mexico now, and here you are also expected to tip big, from the kids who pack your bags at the supermarket (it’s always makes it very uncomfortable if you try to pack them yourselves), to the guy in the empty car park waving and aiding you into a space, to the guy who apparently roams the street at night taking care of the neighbourhood.

I remember once a waitress just kept the change as a tip. The problem was that the change was well over a normal tip and the service had been awful. I was going to leave something, but when I asked about my change, and she told me she has taken it as her tip, it really annoyed me. The fact that she expected it and had assumed it as (an extremely generous) tip was just beyond me.

I think a lot of it is definitely cultural. It’s a really interesting piece, the minefield of tipping!!!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 1, 2013

Your experience with the waitress is unusual, Gina. I think that’s happened to me once in my life. Maybe the ones who give bad service know that taking the tip is the only way they’re likely to get it.

LikeLike

gina4star

June 3, 2013

Yeah that could be true! But the rule in Mexico does seem to be tip, even if the service is bad. A rule which I don’t follow, so maybe that’s why I’ve had a few similar experiences. Rebelling against the rules, waaah! 🙂

LikeLike