When we’re young, life takes place on two physical levels. There’s the world of adults, shifting like storm clouds close to the ceiling, and the world of children, where kids create games to simulate the behavior of their parents and relatives. I could barely figure out what was happening on my own level, so I was completely mystified by almost everything that went on up there.

When we’re young, life takes place on two physical levels. There’s the world of adults, shifting like storm clouds close to the ceiling, and the world of children, where kids create games to simulate the behavior of their parents and relatives. I could barely figure out what was happening on my own level, so I was completely mystified by almost everything that went on up there.

Grown-ups told long, ponderous stories. They talked a lot and drank from short glasses, and as evening turned into night their conversation became sharper and more urgent, as if each person were trying to drown out the others by speaking louder. Their jokes, despite the resulting claps of laughter, seemed pointless and devoid of humor. I’d sit sometimes, under a card table or on the floor next to the sofa, and I’d listen, believing that if I focused hard enough I might understand what they were saying. I approached it the way my mother had taught me to do a jigsaw puzzle, separating the mismatched pieces and turning everything right-side up so I could search for patterns. I would form pairs and then small clusters, and soon the magic moment would arrive when I’d connect the sections and begin to see some resemblance to the picture on the box.

But it never worked that way with adult conversation. They would jump from sports to movies to food. They’d argue about which actor starred in which film, who sang a certain song, and whether Truman was a better president than Eisenhower. They’d disagree about what happened at a picnic decades ago, which beach it was where somebody’s boyfriend almost drowned, or what year they’d gone to that wedding or bought that car. And they’d gossip about aunts and uncles who weren’t there. It all ran together into a wall of noise, as though the whole thing were a sheet of metal that someone was shaking into the sound of thunder. How did they learn their lines, I wondered. How did they know what to talk about, and when it was their turn?

These were all part of the main question that I carried with me everywhere I went: How did anyone find out what they were supposed to do? I asked it a lot, because I was never quite sure. It wasn’t that people were neglecting to tell me, but rather that my brain had the unfortunate ability to tune out instructions at the worst possible moment.

When I was in the first grade, the nun must have explained that she wanted us to circle the words that matched the illustrations in our phonics book. So it shouldn’t have been such a shock when, after creeping up and down the rows of desks and stopping behind mine, she noticed that I was circling the pictures instead, and whacked the back of my skull with her open hand.

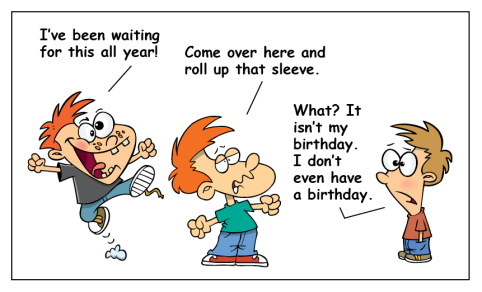

But I was surprised, even though so many human interactions led directly to pain. For example, when my older cousin came over, I knew that at some point he would offer me the end of a coat sleeve, his fist hidden inside. “Want to see stars?” he’d ask. And I’d put my face close and peer in, forgetting what happened the last time we did this, and the time before that.

My godparents’ daughter would pull my hair, hard, the way you would shuck stubborn ears of corn while thinking about somebody who had run over your dog. I can’t remember the reason, and probably didn’t know then, either. There may not have been a reason. I was smaller and we were alone downstairs, and she knew my protests would fail to reach the second floor where the big people were busy sipping their coffee. I dreaded their visits, almost as much for the injury to my scalp as for the unbearable hugs I endured from my godmother, an enormous woman who sold Avon products and was always coated in powder.

One hot summer day when I was nine, a friend of mine held out his left hand. He seemed to be offering me a sip of his root beer.

“Want a slug?” he asked.

The word slug had two meanings for us. It could be a single, swift punch, as in “Did you watch wrestling yesterday? Crazy Luke Graham slugged the referee right in the mouth!” Or it could be a gulp of liquid, especially when shared among a group of boys who would pass a bottle around, each pausing only to wipe the top with part of his filthy shirt. It was a sign of friendship. The only act more sacred was the ritual of becoming blood brothers, which involved cutting our fingertips with a razor blade and then pressing the open wounds together. This seems unthinkable now, given the paranoia about pandemic and our inability to walk more than twelve feet in public without sanitizing ourselves. But we worried less back then, and trusted more. And that’s why I reached for my friend’s soda can so readily, without hesitation and unaware that he was about to drive his fist deep into my stomach. Bent over, bewildered, and gasping for air, I reminded myself that an unexpected slug to the abdomen was how Houdini had died.

Retaliation wasn’t an option. The experience, I realized, was part of my education, a process that would continue to be painful until I learned to pay attention. And with two older brothers, there was no shortage of lessons. They’d grab my wrists and slap me in the face with my own hands. They’d rub their knuckles on my head, or twist an arm up between my shoulder blades until I was sure it would break. They could turn a kitchen towel into a deadly weapon, winding it up to a fine point and then snapping it, like a bullwhip, against the back of my leg, which was often still sore from school, where I’d felt the sting of the nun’s wooden yardstick. On my birthday, every male in my life would seek me out so they could clobber me in the bicep – once for each year, and a final hit for good luck — which left me with a powerful ache, and struggling to appreciate the good luck part.

Retaliation wasn’t an option. The experience, I realized, was part of my education, a process that would continue to be painful until I learned to pay attention. And with two older brothers, there was no shortage of lessons. They’d grab my wrists and slap me in the face with my own hands. They’d rub their knuckles on my head, or twist an arm up between my shoulder blades until I was sure it would break. They could turn a kitchen towel into a deadly weapon, winding it up to a fine point and then snapping it, like a bullwhip, against the back of my leg, which was often still sore from school, where I’d felt the sting of the nun’s wooden yardstick. On my birthday, every male in my life would seek me out so they could clobber me in the bicep – once for each year, and a final hit for good luck — which left me with a powerful ache, and struggling to appreciate the good luck part.

None of it made any sense. Still, it was better than being a grown-up, when I’d be forced to attend those family gatherings. I was concerned that I’d never be able to talk loud enough. The only actors I could name were Fred Flintstone and Godzilla, and I had no idea who Truman and Eisenhower were. Did adults still get punched on their birthday, or offer each other slugs from those tiny glasses? And who was going to take the time to explain the jokes to me?

The jigsaw puzzle had too many pieces. Somehow, it seemed safer down where I was.

subodai213

February 8, 2013

You make me very grateful for having been born female. I never had to deal with this. Oh, I had plenty of bullying, but it was usually from an enemy…certainly not my ‘friends’!

LikeLike

bronxboy55o

February 9, 2013

We didn’t think of it as bullying. It was more that the rules and strategies we used in our games — stickball, johnny on the pony, king of the mountain — spilled over into life in general. And we were all there to remind each other about that.

LikeLike

Tori Nelson

February 8, 2013

This is brilliant and perfectly describes the bewilderment I feel talking to other “grown-ups” most days. Your cousin and my big brother could’ve been friends. It took me one pretty painful year to figure out that his game of “Catch this basketball without your hands” was a trick.

LikeLike

bronxboy55o

February 9, 2013

As rough as it was sometimes, I still wish my son could have experienced that connection I had with cousins, and all the friends I had within walking distance. We were never bored.

LikeLike

Earth Ocean Sky Redux

February 13, 2013

My sentiments exactly. I grew up with cousins all around me, aunts and uncles, everyone eating and laughing. Mostly eating. Italians always cook and eat. We kids had the best time, took the abuse from older cousins like it was a rite of passage, sharing with excitement that we “survived” the pummeling by big cousin Mike. Like you with your son, my children lament that their cousins are distant, both in mileage and emotional connection.

LikeLike

Diane Henders

February 8, 2013

This just confirms my theory that children are small, vicious aliens. You must have been an exceptional child, though – as a kid, I don’t think I ever listened to adult conversations long enough to register their content. Or maybe that has more to do with the fact that I can’t even remember the conversations I had last week…

LikeLike

bronxboy55o

February 9, 2013

I remember sitting in the backyard with my father and a group of other men. I was seven or eight. One of the other men said, “Children should be seen and not heard.” He actually said those exact words. Maybe I had tried to speak, or he was warning me ahead of time. I don’t know. I’m pretty sure my father never said that. But I preferred listening anyway.

LikeLike

TAE

February 8, 2013

The description of the “table conversations” reminds me of my own family. It’s still that way. They can go on for hours, arguing about where this and this town person lived, when that and that happened and so on. It’s still pointless to me. Maybe it’s a European thing?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 9, 2013

Maybe. The strongest impression for me was how much time they all spent together. I shouldn’t generalize, but from what I can tell, those strong family bonds are quickly disappearing. My kids have cousins they’ve never met, and likely never will. So maybe your family’s table conversations aren’t as pointless as they seem.

LikeLike

icedteawithlemon

February 8, 2013

I remember “slugging” each other every time a Volkswagon passed by, rubbing burn marks on our legs with erasers, pulling handfuls of hair from each other’s heads, and sucking “hickies” on our arms until the spots turned dark purple. And I remember breaking a glass, 32-ounce Coke bottle over my sister’s head once after she beat me bloody with a broom handle–we were vicious, brutal animals. And yet, you’re right–the pain we inflicted on each other on the battleground we called childhood was definitely preferable to the frightening, confusing adult world of long-necked bottles, aluminum cans and short glasses. Another great read, Charles.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 10, 2013

It sounds as though your childhood was the perfect training ground for your future career. I wonder if you’ve written about those experiences. If you haven’t, I hope you will.

Thanks, Karen.

LikeLike

The Sandwich Lady

February 8, 2013

What a wondrous meditation on your Italian boyhood, one that reminded me so much of my Italian girlhood. I remember the uncles drinking Seagrams VO from short glasses and arguing over Roosevelt (to the point of near fist-fights), and the punches I’d get from a cousin whenever we inadvertently said the same thing at the same time (usually accompanied by words, “Owe me a Coke.”) The aunts were usually too busy in the kitchen to intervene. As a young adult I remember a get-together with my grown cousins (without the older generation), and was treated to some very funny hilarious imitations of their elders.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 10, 2013

I had no idea what the adults were drinking, Catherine. But I remember that my great-uncle kept a bottle of Chianti on the floor next to him at the dinner table. That way he didn’t have to ask anyone to pass it over to him, and he also didn’t have to share it. And, yes, the women were always in the kitchen — before and after the meal.

LikeLike

raeme67

February 8, 2013

I had a brother was not above giving the girls in the family “Indian burns” as we called them.

Mostly I tried to hide from him. I had a billion kids to play with(9th child in a family of 10) and don’t remember caring much what those grown-ups said it all seemed pointless. Who wanted hear about the weather, the good old days, or current events? B-O-R-I-N-G! I had planets to save, animals to rescue, and dares to foolishly attempt.

Great post! Love your writing.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 10, 2013

It’s amazing how many different methods we had for mutilating each other. And I’d forgotten about the dares — maybe another post.

Are you still blogging?

LikeLike

raeme67

February 10, 2013

Yes, I am still blogging. Would love to hear your dare post. I broke my arm at 7 because of a dare.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 10, 2013

I’ll write one if you do. (That’s a dare, in case you missed it.)

http://raemegoneinsane.wordpress.com

LikeLike

raeme67

February 10, 2013

Okay, I never learned my lessons about dares, so, I double-dog dare you to write yours first!

LikeLike

cat

February 8, 2013

I grew up the only and youngest girl with many brothers … many lessons learned … some valuable to this day … my parents and family spoke in a different language to each other in order to have private conversations … sometimes I would join in and repeat, what they had said … usually that meant for me: Off to bed with no chance of supper … O, well, that all made us what we are today … eh?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 10, 2013

My grandmother and a few other relatives would speak in Italian when they didn’t want us to know what they were saying. It was unnerving. What other language did your parents speak?

LikeLike

Experienced Tutors

February 8, 2013

Do today’s kids still have these rites of passage? Today’s`Cotton Wool Kids` are taken to school by car, not let out to play in the street, not taken on school trips because of Health and Safety` regs. It’s a wonder we survived but. . .I’m glad we grew up then. As usual, great post.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 10, 2013

Much has changed, that’s for sure. We worry a lot more now, and the more we worry, the more we find things to worry about.

Thanks for the comment, ET.

LikeLike

Bruce

February 8, 2013

Great observations from a kids perspective. I really like the ‘mystified by almost everything that went on up there’. Were you always on the receiving end of ‘growing pains’ or did you return some of the lessons? As for the nuns, I haven’t read anything yet which made we wish I went to a Catholic school. Nuns hitting heads and using wooden yardsticks continue to dispel any image of gentle, nurturing servants of the Church. Lastly, I will never, ever argue with your friend ‘icedteawithlemon’ or her sister. Bruce

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 11, 2013

I tend to remember only being on the receiving end, just as I remember the nuns punishing us much more easily than I can recall their kindnesses. It’s probably selective memory. And about Iced Tea With Lemon, she’s one of the nicest people I know. But I wouldn’t argue with her either.

LikeLike

shoreacres

February 8, 2013

Honestly – your descriptions of your childhood (and some of the comments here) seem to come from some alternative universe. Part of the difference is that I was an only child – though I had plenty of friends, I missed out on that sibling bit. I would have been better off with a little more rough and tumble, I think.

But you’re right – we worried less and trusted more. There was so much more freedom, and more acceptance by adults of a very important truth – the world of kids belongs to the kids. We may not have understood adults, but we appreciated the fact that adults were willing to leave us alone.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 11, 2013

That makes me think about so many kids I know whose weekends and vacations are booked solid with organized sports and other activities. They never have to ask themselves, “What am I going to do with my time today?” and they never get together and make those decisions as a group, either. And that’s too bad. When my son was growing up, our neighborhood on the last day of school in June would turn into a ghost town. We never did figure out where all the kids went, but they reappeared in early September.

LikeLike

hemadamani

February 9, 2013

Your post took me back to my childhood. During summer vacations all my aunts and uncles would gather at my grandparents’ place and it used to become a huge congregation of cousins, divided into two groups according to age. We, the older ones would really bully the younger ones, told them stories about ghosts living in certain rooms and in the well at the corner of the garden, which they believed, and we derived some sadistic pleasure in scaring them to hell!! 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 11, 2013

That’s interesting that you remember being part of the older group. But when you were younger, was there an older group there to bully you and scare you with ghost stories? I also wonder if those family gatherings you describe still happen. Or have things changed?

LikeLike

blah blah blonde

February 9, 2013

Burst out laughing at the part about how we can’t walk 12 feet without sanitising ourselves – sad, but true :-/.

Sent via my BlackBerry from Vodacom – let your email find you!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 11, 2013

So the germ paranoia has spread to your part of the world?

LikeLike

blah blah blonde

February 11, 2013

Well, as far as bored and uppity housewives are concerned… We also seem to be going through some sort of OCD trend – every second person will sombrely tell you how they have been diagnosed with either this or bipolar disorder – and they looove their hand sanitisers and motion-activated liquid soaps. In their own friggin bathrooms. Don’t know why they’re worried about the germs on their already-sanitised hands, but yeah…

LikeLike

Allan Douglas (@AllanDouglasDgn)

February 9, 2013

Yessir – life is a one trillion piece jigsaw puzzle… and for many; with a piece missing. I’m glad you made it out of childhood alive, Charles.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 11, 2013

Has that ever happened to you, Allan? You spend days putting together a puzzle, and there’s a piece missing — and then that hole is all you can see.

LikeLike

Snoring Dog Studio

February 9, 2013

How we survive siblings is a thing needing study. It’s quite a feat of human nature to overcome all the fights, the injuries, the pranks, the poison-laced words. Fortunately, we grow up and become good friends, in many cases. For that, I’m very thankful to have my siblings. Wonderful post, Charles.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 11, 2013

Growing up with brothers and sisters can be like training camp for the real world. We end up stronger — assuming we survive.

I hope you’re enjoying your reunited family, Jean. There must be a flood of mixed emotions.

LikeLike

Snoring Dog Studio

February 12, 2013

I’m having the most wonderful of times now, Charles. My mom makes us laugh a lot – and you throw three funny dogs into the mix and things can be quite hilarious. It is a marvelous time, full of possibilities and so many opportunities to get to know my mom better.

LikeLike

Kendall Lyons

February 9, 2013

Because of MY childhood, counseling is taking place. Talk about being “scarred for life.” LOL.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 11, 2013

I imagine most counseling is based, at least in part, on what happened to us in childhood.

Thanks, Kendall. Keep developing those cartoons of yours.

LikeLike

Kendall Lyons

February 12, 2013

I most certainly will!! Thanks so me! Your work as well as the creativity of others really encourages me too!

LikeLike

"HE WHO"

February 9, 2013

Great post! I was among the first of the boomers in our family and there were never many children at our gatherings. But those holiday get togethers are what I miss most about being a kid. Do they still happen with the nuclear families? They sure didn’t with my kids, but the odd time when they did, the guest list paled in size. I remember the arm smacks and Indian burns, but those occurred at or after school. Ah, the good old days. I guess I was scarred for life too, but in a different way.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 12, 2013

It’s hard to generalize, HW. But I don’t know if families typically exist anymore in the form we remember. People tend to scatter, moving to where the jobs are, or where the weather is more comfortable. The pull for siblings and cousins to stay together seems to have evaporated.

LikeLike

"HE WHO"

February 12, 2013

I’m finding that a few of us, very few, have made an effort to reconnect as we age. But you really can’t ever go back.

LikeLike

earthriderjudyberman

February 9, 2013

Well, “slug” has another connotation, too. I’m glad you didn’t encounter one of those in a drink. My parents moved out of my Grammy’s house in Pennsylvania when I was 8. Here, all these years, I thought I was missing something on family connectedness because we lived in Central New York and rarely saw them. Charles, after reading your story, now … I’m not so sure. (We do still keep in touch, though, which is nice.)

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 12, 2013

There are a few more meanings to the word slug, Judy, but I doubt I’d ever heard of them as a kid. And these days, central NY and PA would be considered a short distance, at least in my family.

LikeLike

earthriderjudyberman

February 12, 2013

I just googled it, Charles, and it’s about a 4-hour trip. Maybe it just seemed longer to my folks with two kids in the car. Whether it was longer when I was a kid, I don’t know. We’re talking pre-1964 … when dinosaurs still roamed the earth and it was uphill both ways in the snow. 😆

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 1, 2013

I remember those days well. Our longest family outings consisted of drives to visit friends in New Jersey. It seemed like the edge of the Earth.

LikeLike

sybil

February 9, 2013

I ate cold food most of my life. Not cause it was served cold but because we all enjoyed talking so much at the dinner table. If we had to choose between eating hot food and out-talking each other, we’d pick the latter every time. It was stimulating and fun and happily I still eat a lot of cold food. 😉

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 12, 2013

Too bad we didn’t know each other back then, Sybil. My family could have taught yours the art of eating and talking at the same time.

LikeLike

winsomebella

February 9, 2013

My large family still gathers at least once a year and the biggest difference I see is that the parents of today’s young children who attend now seem to revolve much more around their children than did my parents or I. The little ones often take center stage and are wholly included. No more hiding under the card table or banishment to the kids table now. I can remember time spent in both 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 12, 2013

I’ve noticed the same thing, Stacia. There’s been a definite shift, and it seems to have happened in a single generation.

LikeLike

TheGirl

February 9, 2013

Hello,

I have nominated you for The Versatile Blogger Award. Please check http://www.TheReporterandTheGirl.com for award rules and a list of nominations which include you! Congratulations, you worked very hard and you deserve it, happy weekend and great blog!

TheGirl

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 12, 2013

Thank you, again. I’m not sure if I’m going to do another award post, but I certainly appreciate the gesture. And congratulations to you, too.

LikeLike

Elyse

February 9, 2013

Oh Lord. Being slapped with my own hands — my sister Judy used to do that to me all the time. And then, when she released me, she’d make circles with her thumb and index fingers put them in front of her eyes and taunt me, saying “Never hIt A man with glasses on, glasses on, glasses on.” It was torture.

Glad you were there with me!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 12, 2013

My brother used to do the slapping thing to me, Elyse. And the whole time, he say, “Why are you hitting yourself? Cut that out! What’s wrong with you?” Torture, yes, but still better than being tickled.

LikeLike

mamanne

February 10, 2013

I grew up in a family of girls, so the beatings were less severe! We lived several states away from most of my extended family, so I knew my cousins from semi-annual get togethers but we aren’t really close. I found that so sad when my friends talked about frequent family gatherings such as yours. So my husband and I chose to live very close to my family, and my sisters and their kids. My daughter hangs out with her cousins alot, and they are like siblings to one another. It’s totally cool – I wouldn’t give up that familial closeness for anything!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 13, 2013

If the beatings were less severe, I’d say it was because you got lucky (see icedteawithlemon’s comment above.) And it’s good to hear your daughter is spending time with cousins. That seems to be a rare thing these days.

Thanks for the comment, Ann.

LikeLike

aynotes

February 10, 2013

Reblogged this on aynotes's Blog.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 13, 2013

I appreciate it.

LikeLike

patricemj

February 10, 2013

I always feel a little melancoly when I read these childhood posts of yours…you were such a sensitive kid. The mystery your child self attributed to others, seems more likely a reflection of the burgeoning mind inside of him. He imagined there was so much more to it all than there was. He imagined it had to make some sort of sense.

It’s funny how writers forget the role they play in the creation of the complex worlds they later spend their lives struggling to understand.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 13, 2013

You’re right, Patrice. I still struggle with the illusion that underneath it all, things are supposed to make sense. You’d think I would’ve learned by now.

LikeLike

The YUster

February 10, 2013

This, in a way, explains my irrational need to entertain kids when I’m around them. I guess you feel that as long as you can get along with them, your mind is capable of being simplistic, and therefore, you haven’t yet entered into that fearful responsibility of adulthood.

But I shall learn from this blog and try the old “stars from the sleeve” trick on the next child I see… what a classic!

just kidding

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 13, 2013

Some of those games and tricks from long ago are still around. I wonder if the fist-inside-the-sleeve routine has survived.

LikeLike

The YUster

February 13, 2013

They probably are. And, as for those who consider it bullying, I would say it’s more like a ‘right of passage’… It’s a rough trick; you get hit with it once, you learn from the mistake and you’re all the wiser afterward. After all, it’s a ‘fist-in-a-sleeve’, if it were bullying, it would just simply be called “Fist”. Of course, I’m not sure where my thoughts are on “the wedgy”, there’s nothing very clever about that one… Unless it’s an atomic of course.

LikeLike

Michelle Gillies

February 10, 2013

Boys are extremely physically aggressive. Girls just mess with each others heads. I’m not sure which is worse. I guess the breaks and bruises heal. Sisters usually mean years of therapy.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 13, 2013

Our family was mostly boys, Michelle. I had three brothers and one sister, and out of the eight cousins I saw most often, six were boys. Now I’m wondering what that was like for the girls.

LikeLike

writingfeemail

February 10, 2013

I was the younger sister by three and a half years, so I took a lot of punishment at my sister’s sadistic hands. Some older kids in the neighborhood actually started taking up for me until I grew up and could defend myself. Funny how parents back then called it ‘rough housing’ and ‘just playing’. I think they were often too absorbed in whatever they were doing to be bothered by the ear piercing screams of the wee ones. Yikes!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 13, 2013

Some adults called it “horse play,” which I’ve always wondered about. I’ve never seen one horse grab another by the front hooves and use them to slap the other horse in the face. I bet nobody has.

LikeLike

Val

February 10, 2013

To me it sounds like bullying but I think it’s probably just a very different perception of a very different childhood. I was always a quiet child (you’d never know it now!) and a listener so I actually listened to a lot of what was being said. Unfortunately I can remember very little now. And as for the hitting and slapping rites of passage in childhood, while I’m not an only child there’s so much distance in age between me and my sister, and so few cousins my own age, that I pretty much played by myself.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 14, 2013

I didn’t think of it as bullying then, Val, and I don’t now. It was more like some primitive juvenile boot camp program that helped ensure everyone on the team was adequately toughened up and ready for life.

I’m not surprised you were quiet, and a listener. It still shows.

LikeLike

Val

February 14, 2013

I was also a terrible wimp which, thankfully, I’m not anymore! Thanks Charles.

LikeLike

Stacie Chadwick

February 11, 2013

I was the oldest, with a brother seven years my junior. Nobody ever hit me in the arm, but I did learn how to take long slugs from short glasses.

I love reading your work, Charles.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 14, 2013

My older brothers were thirteen and eight years older, and I have a younger brother and sister who are closer to me in age. So in some ways, it was as though I were the oldest.

Thanks, Stacie. I feel the same way about your writing.

LikeLike

zoetic * epics

February 11, 2013

And I thought -I- was naive! 😉

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 17, 2013

I do catch on, eventually.

LikeLike

simonandfinn

February 11, 2013

You are such a wonderful writer. I loved this piece… and these descriptions in particular: adults “shifting like storm clouds close to the ceiling” and your hair getting pulled “the way you would shuck stubborn ears of corn while thinking about somebody who had run over your dog.” So imaginative –

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 17, 2013

Thank you, Melissa. I always appreciate your generous feedback. And I always enjoy your amazing cartoons, as well.

LikeLike

Betty Londergan

February 14, 2013

Boy I guess that my upbringing was completely gentle — even with 5 older brothers and sisters! Of course, sisters know how to unhinge you emotionally so it’s not exactly pain-free either. Our car games were always filled with savagery, though — we’d play Rock Paper Scissors and when you lost, your opponent got to take two fingers and slap the living bejeezus out of your arm. We’d arrive at our destination covered in welts. (Why did my parents think 6 kids on a 2 day car trip constituted a vacation?? particularly since it ended in St. Louis in August to visit my German grandmother who had no air conditioning??) Oh these mysteries of the universe! But I love that you were so intent upon understanding adult conversations — I have to say, I never even tried to decipher them. You were obviously perceptive and questioning even as a young lad!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 17, 2013

Based on your comment and a couple of others, I guess sisters could be as vicious as brothers, Betty. I didn’t know, because my only sister is four years younger than me.

LikeLike

Patti Kuche

February 14, 2013

That confusing family jigsaw puzzIe! I grew up with five brothers, none of whom seemed cognitive of the fact that I was, still am, female let alone a little girl in the middle of the male jungle that was my forever fighting family. Once I ended up in hospital for surgery to a shattered hand from a kick up the backside – my much older brother wore very pointed shoes back then, and another time it was stitches to the head when I walked into the path of a flying rock. Indian burns, arm punches and wrestle moves meant they really loved me and I was getting attention, yay!

Did you ever overhear any of your relatives . . . . curse and/or swear? I still remember the horror of hearing an uncle proclaim to the noisy room of drinking relatives that “women p!ss louder than men.” I was shocked and horrified and horribly confused as to whether this constituted a sin for the next week’s confession!

Hope it is OK to admit how much your wonderful piece has made me smile! Somehow we survive it all!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 17, 2013

I did hear my relatives curse, but as kids we thought it was hysterical. I do remember being shocked to learn that the President of the United States had been caught swearing on tape.

Thanks for the kind words, Patti.

LikeLike

Barbara Rodgers

February 15, 2013

I didn’t know if I would laugh or cry when reading this, Charles. I can relate to the family gathering stuff – my sister and I were the “baby” cousins in a pack of older and much older male cousins who terrified us. And when we visited the adults they would all make comments about our shyness and other personality and physical flaws. “Why doesn’t she say anything?” “Why doesn’t she like blueberries? We all like blueberries!” It wasn’t safe anywhere and what added to the problem was that I was, and still am, very gullible and often slow to catch on. But you’ve put a humorous twist on an awfully painful experience. Well done!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 17, 2013

I was also described as quiet and shy, Barbara, as though it were some problem that needed to be fixed. But then, most of the time adults were telling us to shut our mouths, anyway.

LikeLike

dearrosie

February 15, 2013

Oh what memories Charles. I had to laugh at your looking up your cousin’s sleeve for stars because I’ve got a couple of older brothers and I can imagine one of them doing that to me.

My brothers were always punching me. When I tried punching them back I’d end up hurting myself…

My oldest brother sat next to me at the dinner table and would always steal treats like my fries off my plate and when I cried and asked my Dad to help my brother would simply take another one. And laugh at me.

I was also told “children should be seen and not heard!” Sigh…

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 17, 2013

I had the same experience, Rosie — punching my older brothers and just hurting my own hand. Definitely a no-win situation when you’re little.

LikeLike

rangewriter

February 15, 2013

You say you were never bored as a kid. I suspect, Charles, that you are never bored, period. Bored is a state of mind for boring people which you are not and have never been. Perplexed, perhaps, but never bored.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 17, 2013

Linda, the only thing that really bores me is when I find myself trapped and listening to someone talk endlessly about how much they know. That’s when my mind starts to wander. It happens a lot.

LikeLike

Damyanti

February 15, 2013

I had my share of being bullied by cousins during vacations — but being the older of two sisters and living far away from relatives was a boon, I think. As usual, you have a great way of bringing humor and insight into the most mundane of situations.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 17, 2013

It might be interesting to write about the differences in the relationships between cousins, and those between siblings. They’re definitely distinct.

I hope you’re well, D. It’s good to hear from you.

LikeLike

Shakti Ghosal

February 16, 2013

What could we do to align the different worlds you speak of? Are these differences real or in our minds? As we sift through our memories ( the way you have done), we can indeed look at our own perceptions and the thoughts they generate.

Loved your post.

Shakti

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 18, 2013

And then there’s another element: our memories change over time. Each time we take them out for examination, the very process causes more change.

LikeLike

Amiable Amiable

February 16, 2013

I’m reminded of the grownup men (uncles, grandfathers) who always pretended to steal my nose. I don’t know if I fell for it every time or, out of sympathy (because they seemed to really think they were stealing my nose), I just let them take it. I was always so relieved that they put it back. It was a crap shoot since they had often drank from those short (and tall) glasses before the nose stealing commenced. (Please tell me you know what I’m talking about. Please.)

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 18, 2013

I know exactly what you’re talking about, AA. My father and several uncles used to pull that one on me all the time. (It got really annoying once I reached my mid-twenties.) But I never really understood the trick — they’d slip their thumb between two fingers and say, “I’ve got your nose.” But their thumb didn’t look anything like my nose. They couldn’t even fool me, and I was in a perpetual fog.

LikeLike

Amiable Amiable

February 18, 2013

Exactly! It never looked like a nose! I hate to say that I’m relieved you knew what I was talking about, because that means you suffered nose trauma like I did, but it does give me a sense of relief to know I wasn’t alone.

LikeLike

ShimonZ

February 16, 2013

This is a very moving piece. Though it’s different from anything I have experienced, I was able to identify with the narrator, and to feel for him. It wasn’t completely clear for me, whether it was meant to be humorous or not, especially because of the illustrations. But to my mind, it was tragic, even if humorous. I believe that someone who had endured such torture would truly be scarred for life. Since I started reading blogs, I have come to realize that for many, childhood has been a difficult ordeal. It’s a great blessing, when we can get past it, and live our lives according to our choices, and personal vision of what life might be. Thank you for sharing this. It is a post that has stimulated long thoughts, and reflection on what we can gain from all that suffering.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 18, 2013

I’m not sure I’d call it suffering, Shimon, although it was a struggle at times. I guess any learning process is, to some degree. Thank you for reading, and for your thoughtful comments.

LikeLike

Sandra Parsons

February 24, 2013

“How did they know what to talk about, and when it was their turn?” Interestingly, even as an adult having (supposedly) adult conversations I too often find myself thinking that people either don’t know what to talk about (i.e. blubber complete nonsense) or don’t know when it is their turn (i.e. speak on top of each other or try to drown others out).

Yikes on the physically scarring childhood experiences though, Thankfully, I don’t remember it being this bad – and I wasn’t exactly one of the popular crowd. I guess being a girl helped, and also maybe we Germans aren’t quite as “macho” altogether 😉

Great read as always, Charles, thank you for letting us peek into your childhood memories.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 24, 2013

I think part of the confusion came from my experiences at Catholic school, where we were forbidden to speak unless we’d been called upon or we had raised our hand and given permission to say something. So there was this rigid system of rules and then this confusing free-for-all. I still haven’t figured it out. It sounds as though you haven’t either.

LikeLike

JSD

February 28, 2013

Oh, does this bring back memories. We endured a ‘playful’ spanking on our birthday with one smack for each year and an extra to grow an inch…or some stupid thing like that. It’s amazing what was so normal for our childhood is thought nowadays to be bullying or abuse.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 28, 2013

I agree. It sounds like bullying or abuse, but it wasn’t. It was something else, something hard to explain. I guess you had to be there.

LikeLike

JSD

February 28, 2013

Maybe just a rite of passage?

LikeLike

lostnchina

March 25, 2013

I’m starting to feel quite sorry for you, Charles. But I’m sure you retaliated in your own way. It’s just much easier getting sympathy votes this way 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 25, 2013

It was good training for the way the grown-up world works, Susan. I don’t think I ever even questioned it.

LikeLike

bobcomeans

March 27, 2013

After reading this post, I had to write about Family Gatherings as well. Though not as well put as yours, I try. Thanks for the inspiration! “He Called Me Jim,” is the title of my post. I’ll be back often. Bob Ishouldhavecalledinsick.com

LikeLike

bronxboy55

March 29, 2013

Thanks for letting me know. I’ll be sure to read it.

LikeLike