It’s that time again: Super Bowl week. I know this, not because I follow football in even the slightest way, but because I’ve noticed the potato chip and Coca-Cola displays at the grocery store. Built like shrines to the gods, these stockpiles of snacks will be inhaled by a hundred million people in six hours. This is just enough time to complete the pre-game and post-game shows, four fifteen-minute quarters of actual football competition, a forty-five-minute halftime extravaganza, and a lot of expensive commercials created to get you to eat potato chips and drink Coca-Cola.

From http://www.kshs.org

I don’t have many positive memories related to the sport. When I was about eleven, my best friend got one of those electric football games that had plastic players and a metal field that would vibrate when you flipped the switch. We’d line up our teams with great care, and then sit there for a long time listening to this thing buzz and staring at our little men as they wandered around in all directions, quivering like mad and eventually getting stuck against a side wall or clustering in bunches in the corner like tiny bumper cars. It was, I imagine, not much different from putting on show tunes and watching termites attempt to perform Guys and Dolls. Every now and then my friend would announce that he’d gotten a first down, a development that always escaped my attention but that he never failed to see. Touchdowns and field goals would follow, along with other assorted scoring opportunities based on obscure rules that I was pretty sure he was making up on the spot.

Sometimes, when the older boys had a thirst for human blood, we played real football on an empty lot riddled with small rocks and shards of broken glass. We had only the ball, and no other equipment whatsoever. Helmets were for sissies, we decided, and complaining of pain after being slammed to the ground and crushed under a pile of snarling teenagers would just mean you’d be picked last the next time we played. If we didn’t call it the Stupid Bowl, we should have. We were a bunch of morons.

I preferred baseball. For one thing, in other sports the opposing team spent most of its time trying to take something away from you, inflicting physical harm and verbal abuse in the process. It was too much like real life. Football, for example, was nothing more than the offense bulling its way through, while the defense did whatever it could to knock you down and get you to fumble the ball.

Basketball was the same, except you wore shorts and were required to dribble and avoid committing a three-second violation. No one ever explained the three-second rule to me, or how the referees could possibly keep track of where everyone was and for how long. I got called on it a lot in gym class, usually because I had to stop and re-tie my sneakers in the middle of play.

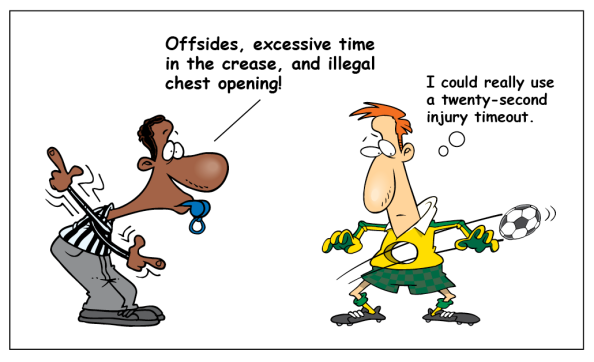

In both hockey and soccer, there was an infraction referred to as off-sides. Again, I’ve never been able to understand this rule, beyond the simple conclusion that it’s designed to keep you from wanting to score a goal too much. The result, often, was an unbearably long game that ended in a tie. Frequently, a scoreless tie. This was like going to a restaurant, ordering a meal, waiting for your dinner to be served, then leaving without eating anything.

In both hockey and soccer, there was an infraction referred to as off-sides. Again, I’ve never been able to understand this rule, beyond the simple conclusion that it’s designed to keep you from wanting to score a goal too much. The result, often, was an unbearably long game that ended in a tie. Frequently, a scoreless tie. This was like going to a restaurant, ordering a meal, waiting for your dinner to be served, then leaving without eating anything.

I found myself playing lacrosse once, and like hockey, its bizarre regulations included something called a crease, which I think is an invisible fourth dimension that players either must stay inside of or avoid entering at all costs. I’m still not sure.

These sports seemed to have a common element: they all had commentators and coaches who rattled on and on about intricate strategies and match-ups, deep explanations of what worked and didn’t work, how they needed to go back to the fundamentals, and what they intended to accomplish next game or next season. The only thing I ever saw was a bunch of lunatics chasing after a loose ball or puck, unsure of where it was headed and knocking each other around to relieve their frustration.

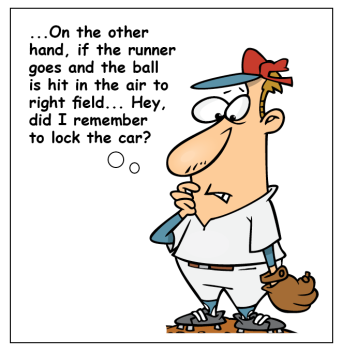

But baseball was different. Baseball involved thinking, rather than reptilian-brain reflex responses. There was time to plan ahead. And there was room for real strategy, because there were just so many things that could happen, and each thing had a correct reaction.

My younger brother and I played baseball every chance we got. We played in the street, using flattened beer cans and manhole covers for bases. We played on concrete playgrounds, and on any available stretch of grass. We pitched to a rectangle we’d drawn with yellow chalk on a brick wall. In the winter, we played in the house, arranging the living room furniture like an infield and using a rolled-up sock for a ball.

We watched professional games on television. And once or twice a year, our father took us to see the Yankees or the Mets play in person. One summer, we went to the Mayor’s Trophy Game, an annual fundraiser in which the Yankees and Mets played against each other. My brain nearly exploded with excitement, but I’d also been backed into the corner of team loyalty, and chose to focus instead on eating as many hot dogs as I could. This was in the early 1960s, when you could sit in a box seat for three dollars, or the bleachers for seventy-five cents. When players had names like Ernie and Vic, Roberto and Duke, Sandy and Moose, and the very best of them made less than a hundred thousand dollars.

Of course, I had no idea about players’ salaries when I was a kid. I doubt I’d ever even considered the fact that they were paid at all. Baseball was a game, not a job, and I’d have paid them just for a chance to step onto that field and touch the bases. I dreamed of someday getting a close look at the three monuments in centerfield at Yankee Stadium, vertical granite slabs that looked exactly like the headstones I’d seen when visiting my grandparents’ graves at the cemetery in Queens. I wasn’t certain, but I thought the players might have been buried right there in the outfield.

At one game, Mickey Mantle hit a five-hundred-foot shot over the black screen in dead center. I may have seen it, but more likely I was looking around for a food vendor. Still, I was there. I remember standing and cheering about something; it had to be either the home run or the guy selling Dixie Cups – cardboard containers filled with half vanilla and half chocolate ice cream that you ate with a flat wooden spoon.

World Series games were played in the afternoons back then, in the first week of October, when you could tell the inning by how close the shadows were to the pitcher’s mound. There were two leagues, as there are now, but each had just ten teams. The best record at the end of the season got you into the World Series. No playoffs or division championships. No slipping into a side entrance off Wild Card Alley. You either won the pennant or you didn’t. It was pure, and it was fair. I remember running home from school to catch the last couple of innings. And sometimes, on days when I loved the world more than anything, the nuns would turn on the television and let us watch the game right there in our classroom.

The Super Bowl had not yet been born. The highlights of the year were Easter, summer vacation, the World Series, my birthday, and Christmas. It was the anticipation of each event that helped sustain me from one to the next. People say it was a simpler time, and I guess it was. Potato chips came in two flavors, and there was Coca-Cola and whatever it was other people drank. There was vanilla and chocolate, the Yankees and the Mets, baseball and all those strange, inferior sports.

And there was time to think.

On second thought, he explains it better.

icedteawithlemon

February 1, 2013

Beautiful. And the fact that I’m a baseball fanatic who believes that all other sports pale by comparison does not bias my opinion in any way. I’ve always felt that baseball was the great equalizer–that even the smallest guy (or girl) on the field could still contribute in monumental ways–and for the short girl who became a short mama of short sons, that was important. Maybe we couldn’t stand up to 300-pound tackles, but we could steal from one crushed-can base to another before the catcher even had time to react.

Thanks for the trip down Memory Lane, Charles. (And Mickey Mantle?! In the words of Harry Caray, “Holy Cow!”)

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 1, 2013

You’re right, Karen: Some of baseball’s greatest players have been on the small side. And speaking of small, did you mean Phil Rizzuto, rather than Harry Caray? You know, those were your Cardinals who beat the Yankees in ’64. That was Mantle’s last World Series.

LikeLike

icedteawithlemon

February 1, 2013

I think Rizzuto and Caray both popularized the phrase (Caray even has an autobiography with the same title). I wish I could say I’m sorry that my Cardinals took a World Series title away from your Yankees, but the best I can do is offer my sympathies. 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 1, 2013

You’re lucky Sicilians don’t hold grudges. Anyway, I’m still trying to get over the Yankees being swept by the Dodgers in ’63.

LikeLike

Jac

February 1, 2013

Sicilians don’t hold grudges?

LikeLike

icedteawithlemon

February 2, 2013

Ha! You almost got away with that one. “Sicilians don’t hold grudges”–and yet you’re still sore over a 50-year-old loss? Well played, Master Charles. In the Ozarks, we call that “talking out of both sides of your mouth,” an ability most commonly shared by those in political office. Are you SURE you don’t have a political career in your future? 😉

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 2, 2013

We don’t hold grudges, but we tend to stay crabby for a really long time. And now that you’ve reminded me that it’s been almost fifty years, I feel even crabbier.

LikeLike

theshrevest

February 8, 2013

bronxboy55 – I have a hard time feeling sorry for Yankees fans at all. I mean, you guys have twenty-seven other World Series trophies, right?

On the other hand, there’s a lot of sorrow that goes along with being a Braves fan. Fourteen straight division titles and only one World Series trophy to show for it… Always so close, but always so far away.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2013

I was really a Mets fan when I was a kid, because I love underdogs. When I’d get upset after a loss, my father would remind me that the Mets weren’t going to send me any money if they won. That’s when I realized there was a difference between liking a team and being part of a team. The Yankees have twenty-seven titles. Just as my father predicted, I’ve never received a single World Series bonus.

The Braves had a streak that was unprecedented. Any team can win in the playoffs, but fourteen straight division titles is unbelievable.

LikeLike

theshrevest

February 8, 2013

I should clarify – when I say “you guys” I mean “Yankees fans”. It irks me to no end when folks say “We won” or “We lost” when in fact all they did was sit on the couch eating potato chips and drinking Coca Cola. I commented in a bit of a rush earlier.

At any rate, I thoroughly enjoyed this post. Any chance we’ll see you posting some more baseball memories during the season?

LikeLike

Diane Henders

February 1, 2013

I think I lost my love for baseball the day I was playing shortstop and my ankle was temporarily dislocated when it got in the way of a ball that had been batted by Gorilla-Man. I limped around swearing until I could unclench my fists enough to drive myself home, at which point I tripped over the dog and my ankle snapped back into alignment with an audible click. My leg was purple from the knee down for weeks. Your football compatriots would have been contemptuous of my wimpiness.

But you’re right. Life was simpler then. 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 2, 2013

That hurt just reading it. I hope Gorilla-Man was sympathetic.

LikeLike

Diane Henders

February 3, 2013

Actually, no. It was a pick-up game. I didn’t realize that was short for “pick yourself up off the ground and stop whining”… 🙂

LikeLike

mostlikelytomarry

February 1, 2013

Beautiful post. Although I am not a big fan of any sport in particular, I do love the feel of a real baseball game. Sitting in the stadium, eating peanuts, and worried every foul ball is going to come at my head. It is a little bit of magic.

I am off to buy several different flavors of chips, and Pepsi instead of coca cola to watch a game I don’t much care for. Doesn’t make sense, but I do it anyway 🙂

Great post, as always. Thank you.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 2, 2013

I have no problem with the chips, or even that you’ve allowed yourself to be drawn into the Super Bowl hysteria. But really — Pepsi?

LikeLike

mostlikelytomarry

February 4, 2013

Definitely Pepsi. Sorry to disappoint you 🙂

LikeLike

"HE WHO"

February 1, 2013

Sound to me like you have all of the games down pat. I’m in awe of you. You saw the Yankees play live, I remember in grade five or six listening to the World Series in class. We would hide our transistor radios in our pockets with the earphone in our ear and the cord running down our sleeve to the radio. I’m sure the teacher knew. But it was terrific. I remember Mantle and Maris coming to bat. I was always hoping for a home run. If I’d have known you then I would have said you were living the dream. I went to a Jays game a couple of years ago and it was like watching paint dry. Everything seemed bigger and better when I was young. But on Sunday I’ll be watching the game, eating my potato chips and chugging root beer. I’m pulling for the Ravens.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 3, 2013

I guess we were living the dream, but we didn’t know it. I can remember sitting in the right field box seats at Shea Stadium, with the Mets playing the visiting Pirates, and Roberto Clemente was standing seventy-five feet away. But I didn’t really appreciate how great he was. I just saw him as an opposing player who might do something to cause my team to lose. Where were you living when you had the transistor radio at school?

LikeLike

"HE WHO"

February 3, 2013

Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. It would have been the late 50’s. I heard a few stories similar to yours from a buddy who grew up in Brooklyn. He, however, eventually spent most of his time at Yonkers rather than at the baseball stadium.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 3, 2013

I went to Yonkers Raceway a couple of times, once with my father and at least once with an older brother. It seemed boring then and just as boring now — or maybe I’m just incapable of appreciating the nuances of horses running around a track.

It’s interesting that you were rooting for the Yankees while growing up in Winnipeg.

LikeLike

"HE WHO"

February 3, 2013

LOL The only baseball team we had was called the Winnipeg Goldeyes, named after a fresh water fish. (I love smoked goldeye). The World Series was huge in Canada even back then, despite the fact that the Goldeyes were never in the same league. The Yankees were the most famous team there was, as well as the Brooklyn Dodgers. I used to play baseball as a youngster and all the teams had names like the Cubs, Red Sox, etc. There weren’t that many teams in the league in those days. Something like the big six in hockey. Before the expansion teams came into being.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 4, 2013

You ate smoked baseball players?

LikeLike

"HE WHO"

February 4, 2013

Good one. No. I ate the “fish”. They serve it to you head and all. You simply cut down the side and the flesh peels away from the bones, Like meat melts off a really great rack of baby back ribs. But you can only get smoked goldeye (fish) in Manitoba. But…I’m sure the baseball team sometimes got smoked when they played.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 5, 2013

I knew I was going to be sorry I asked.

LikeLike

Betty Londergan

February 1, 2013

I just love when you take the time to write and you give us this true and achingly sweet picture of what life was like in the old days.. when we were growing up. (And let’s not forget that, unlike football, fans of baseball don’t seem to feel the need to witness as many concussions and as much brain damage as possible to call the game “exciting” — that’s certainly a point in its favor!)

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 3, 2013

Back then, the world of professional sports existed on a different plane, I think. It was as though these guys weren’t real people. I remember getting a baseball card in 1964 for a Cubs player named Ken Hubbs. There was a thick black line around his picture because he’d died the previous winter in some kind of accident. It was almost unimaginable to me that a baseball player could get killed. And we never thought about traumatic head injuries, even for football players or boxers. Fortunately, that’s changing.

LikeLike

Jac

February 1, 2013

I remember when you and Michael played baseball in the living room. I was the 3rd base umpire. I also remember when you had wrestling matches and I was the referee who had to say “ding, ding, ding.” Come to think of it, you guys never let me play anything with you.

I’ll just remind you that I’m Sicilian, too…

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 3, 2013

Why would we let you play? You were the worst umpire in the history of baseball. I’d get rug burns sliding into third base and you’d call me out every time. I’ll hand it to you, though: you were good at saying “ding, ding, ding.”

LikeLike

Jac

February 3, 2013

I always called you out because Michael was smart enough to pay off the Sicilian umpire. Capisce?

Ding, ding, ding

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 4, 2013

More proof that baseball is just another business. Even then, it was all about the money.

LikeLike

earthriderjudyberman

February 2, 2013

Baseball – a game I avoided playing because I have problems with depth perception – is one I do enjoy watching. I can still recall the childish ferver of my classmates as they rooted for the (sorry, Charles) Brooklyn Dodgers to trounce the Yankees.

Your recall of those games is pitch perfect. Then, it seems that children were allowed to make up the rules on and just have fun. Now, too many parents – and some coaches – zealously push the kids for that all important cheap trophy. That’s a shame.

As for football, my hubby has to re-explain the rules to me during every Super Bowl. I only watch it then for the commercials. 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 3, 2013

I was too young to remember the Brooklyn Dodgers. Their last season in New York was 1957, when I was two. My father despised both the Dodgers and the Giants after that, not because they were rivals to the Yankees, but because they’d left for California.

Thanks, Judy. I hope you enjoy the game — or at least the commercials.

LikeLike

strawberryquicksand

February 2, 2013

Good Lord, I loathe sport! I used to be made to play netball all through primary school by virtue of the fact that I had two arms, two legs and a fanny (i.e. if you were a girl, you were on the netball team due to the fact that the entire school population was about 42). I used to cop the goal keeper position because that was where I could do the least damage. I was not allowed out of my teensy semi-circle, and only saw any action when the opposition’s goal shooter got the ball and attempted a shot. In which case, they usually made it because I never EVER managed to bat the ball out of the opposition’s goal shooter’s hands when she went for a shot. Then in high school when I was made to participate (and I use that word loosely – does looking for four leafed clovers in the far corner of the playing field constitute playing?) in soft ball, the one and only time the ball came anywhere near me, I grabbed it, ran, and flung it towards the (insert title of player who ought have been catching my throw here), I succeeded in hitting the only post on the entire field. Nope, sport and I don’t mix.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 3, 2013

I think a lot of kids get thrown into a sport unprepared. If no one explains the game to them properly, and if they find themselves playing with — and against — other kids who have a lot of experience — it can be pretty unpleasant.

By the way, I have to admit I’d never heard of netball and needed to look it up. I was surprised to learn how popular it is, all over the world.

Thanks, Yvette.

LikeLike

strawberryquicksand

February 3, 2013

Haha – really? I’m guessing that basketball takes precedence over netball where you are from. And yeah, by the time I’d played netball all through primary school I was still pretty bad at it but at least I knew the rules of the game. 🙂

LikeLike

Tori Nelson

February 2, 2013

This is so, so good. Sharing with the Freshly Pressed gods because this needs to be featured! I’m still fascinated at all the impossible rules and plays and ins and outs of each sport. This might be why, like you, the only sporting event that sounds like any fun to watch is Baseball. I at least have some small clue as to what’s going on!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 3, 2013

I live in Canada now, Tori, so hockey is the basis of every conversation that takes place between September and June. I’m still trying to understand how you can have set plays with a bunch of guys in heavy padding skating around on ice and chasing after a small black disk that’s zipping across the rink at two hundred miles an hour. And then there’s another sport called curling. When they show a replay in slow motion, you can’t even tell the difference.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2013

Freshly Pressed! How did you do that?

LikeLike

Allan Douglas (@AllanDouglasDgn)

February 2, 2013

Enlightening and entertaining post, Charles. I can relate to much of it: as a kid, anything that involved catching, hitting or throwing a ball (or ball-like object) I stunk at. I was good at cross-country running, gymnastics and wrestling. Unfortunately the captain of the gymnastics team never got the hot babes.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 4, 2013

I suspect you’re exaggerating your lack of athletic skills, Allan, but I appreciate the comment. It’s always good to get your feedback.

LikeLike

dearrosie

February 3, 2013

Oh gosh I enjoyed that Charles 🙂 I didn’t go to a convent school, and baseball wasn’t a sport where I lived, so I know nothing about the history of the World Series, but I remember when there was just one kind of Coke and two kinds of potato chips!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 4, 2013

I don’t really wish I could go back to that simpler time, Rosie, because in many ways it wasn’t simpler. But I do think we have too many unnecessary choices to make now. Every product comes in so many varieties, and the result is this illusion that we have more power — we can buy the orange juice that’s exactly right for us. It’s just another distraction.

LikeLike

Catty O'C

February 3, 2013

Really good, very insightful!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 4, 2013

Thank you, Catty, for taking the time to read and comment.

LikeLike

Snoring Dog Studio

February 3, 2013

Stupid Bowl. Foolsball. Just can’t stand it. Why would anyone have to think? The announcers do it all for the fans. The commercials drill into us what we should eat and wear and drive. I know I offend, but honestly, it’s all just a big cult. And baseball has been replaced by football as the national American past time. It’s all so wrong.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 4, 2013

It’s still our fault. We’re told what to buy and we buy it. We’re told what to believe and we believe it. We’re told who to admire, and we don’t just admire — we worship. And usually, we pay for the privilege, too.

LikeLike

Snoring Dog Studio

February 4, 2013

Well said. How sad, too.

LikeLike

writingfeemail

February 3, 2013

Being Southern American, football is almost a religion in my neck of the woods. My son played basketball, football and baseball – baseball winning out in the end when the opportunity to play year round with traveling teams presented itself. So we are clearly in the baseball field with you!

Still, have to watch the superbowl and all of the hype – commercials, food, half-time show, etc. In fact, must go do that now! Happy Bowling!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 4, 2013

Thanks, Renee. I hope you had fun watching the game.

LikeLike

Rufina

February 4, 2013

I am not a sports fan. My mother, a 70-year old Filipino, watches hours upon hours of American baseball and can tell you all the recent stats and her favorite players! Reading that was more fun than watching any sport, for me. A welcome distraction. 😉 I did watch the half-time show last night. Wish I had had a hotdog and a Coke…

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 4, 2013

Your comment reminded me of how many stats I’ve had in my head since I was about ten years old. I wonder if they’ll still be there when I’m seventy. (I hope so. It isn’t that far off.)

Thanks, Rufina. I hope your mother is doing well, and looking forward to the new season.

LikeLike

Daily Rants with the Bitch Next Door

February 4, 2013

I want to go to the land before the hype. Somehow this year I managed to escape the hype, maybe because I have been hibernating and haven’t really gone out in public. But I didn’t even know it was the superbowl until…the day before! Shocking! I call it a small success. (And I still don’t know who won, nor do I care) ps..nice work. I enjoyed reading it.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 4, 2013

Were you more aware of the Super Bowl last year, when the Giants won? Championship games are harder to ignore when one of the teams is local.

LikeLike

Daily Rants with the Bitch Next Door

February 4, 2013

Oh god, yes. It was all I heard about. You’re right, when it’s local, the entire tri-state area is a madhouse. And I’m hiding in the bathroom rocking in the corner waiting for it to be over..

LikeLike

Sandra Parsons

February 4, 2013

Hi Charles, I thoroughly enjoyed reading this – as always, really – and I intended to write a thoughtful and relevant comment but then I got distracted by that last link and ended up watching George Carlin videos on youtube, bouncing the baby in between. What a way to spend my day off, thanks a million 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 4, 2013

I did the same thing when I first found the video. I’m glad you had a day off, and got to enjoy it. Thanks, Sandra.

LikeLike

Stacie Chadwick

February 5, 2013

I love your definition of the crease in LAX, Charles. I have three children who play or have played, and I never understood any infraction called within that seemingly mystical place. Maybe it’s a joke, made to fool people like you and me. No skin off my back though, Cool Ranch Doritos were on super-sale yesterday so while the ref calls fouls, I’ll hide behind the bleachers with my stash.

=)

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 5, 2013

I like Cool Ranch, too, partly because every other flavor of Doritos — and there are thousands — all taste exactly the same. Don’t they?

LikeLike

Stacie Chadwick

February 5, 2013

No way! There are subtle, but important differences in all flavors, Cool Ranch being the absolute best. =)

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 5, 2013

You’re more discriminating than I am. But I already knew that.

LikeLike

She's a Maineiac

February 5, 2013

Another great post! I used to love watching baseball. Until Buckner lost that ground ball and they lost the World Series. Still not over that. I loved this post though, and that’s an accomplishment on your part because I grew up with football and love everything about the game.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 5, 2013

It’s time to forgive Buckner, don’t you think? The drought is over and they’ve won twice in the last ten years. (Have you ever seen Fever Pitch? It’s one of my favorite baseball movies.)

LikeLike

She's a Maineiac

February 7, 2013

A big congrats on the FP, Charles! Wahooooo!!!!

LikeLike

She's a Maineiac

February 7, 2013

(and no, it’s never time to forgive Buckner…)

All right, I will. But only because you said so.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2013

Thanks, Darla. And Buckner thanks you, too.

LikeLike

Tom Marshall

February 5, 2013

You have stirred up memories of empty lots with a tan Rawlings mitt and a baseball cap pulled down to keep the sun out of one’s eyes. Players like Catfish Hunter and Hank Aaron were memorable, and especially the Topps Baseball Cards, buying the small packages at the local store for a few cents, and the flat stick of gum. I collected at least four 1974 Hank Aaron Special cards before getting one with him holding the bat. I watched him break Babe Ruth’s home run record in 1974. It was an amazing time. I did not have a baseball team I followed because Dallas and Pittsburgh’s football teams kept my attention. But the atmosphere was there in the empty lot where we played ball. Thanks for stirring up the memories. I could go for a Coke right now and summer weather to enjoy a game.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 6, 2013

I may have asked you this before, but I wonder if you’ve ever heard of vintage baseball. They’re located mostly in the Midwest, so I’d be surprised if you haven’t. I’d love to see a few of their games.

Thanks for the great comment, Tom. Only three or four more months of cold weather. Maybe five.

LikeLike

Wyrd Smythe

February 6, 2013

You and me both, homie! In my world there is only one sport, and that sport is baseball.

I was watching Moneyball (again) the other night. A key-note line for me is in the scene where Hill’s character shows Pitt’s character the Jeremy Brown home run clip. Pitt’s line is, to me, the canonical statement about baseball, “How can you not be romantic about baseball?”

It’s one of those things that things are “as American as!”

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2013

Moneyball was in our theater for just one week and I wasn’t able to see it. I’ve been looking for it ever since. Field of Dreams and The Natural are two of my favorite baseball movies, but I think I’d have to put A League of Their Own at the top of the list.

LikeLike

Wyrd Smythe

February 8, 2013

All three you named are in my Top Faves along with Bull Durham. I have a fondness for the Major League movies, too; my Minnesota Twins appear in the third one.

LikeLike

Things You Realize After You Get Married

February 7, 2013

I do think the whole thing has become one glorified event nowadays. However, I have recently gotten into the game (read: I finally understand how it works), and I kinda like it. To be honest, I’d still watch it even if all the “extras” were gone! Congrats on being FP! 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2013

Understanding the game, or at least being able to follow it, does make a difference. After moving to Canada, I tried to watch curling, but just couldn’t figure it out. I’ve had the same experience watching television game shows in a foreign language — no matter how long I sat there, I could never grasp what the audience was cheering about.

Thanks for the comment.

LikeLike

Things You Realize After You Get Married

February 8, 2013

You live in Canada as well? …I live in Canada and I STILL don’t get curling (or our 2 national sports of lacrosse or hockey)! :0

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2013

Lacrosse is a national sport? I didn’t know that.

I’m in PEI, by the way.

LikeLike

anbrooks2013

February 7, 2013

It’s interesting that you like baseball but dislike football. I love watching football on TV but not live and I hate watching baseball on TV (unless the Texas Rangers, Boston Red Sox or Braves are playing) but watching it live is amazing to me.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2013

When I was a kid, the average major league baseball game took between two and two-and-a-half hours. Now, with commercial breaks and the endless parade of relief pitchers, watching a game on television can be a long ordeal. But I’ve always been amazed by how quickly nine innings go by when you’re watching it live.

I don’t dislike football. I just like baseball much better — kind of similar to how I like pizza way more than I like grilled cheese.

Texas, Boston, and Atlanta. Have you moved a lot?

LikeLike

TAE

February 7, 2013

I put this aside for later reading, and, because I have the attention span of a squirrel, I never got to it. Your dislike of football I can understand very well. Somebody calls you from the kitchen and you miss a whole move, because you turn your head away from the TV. I can never feel any suspense by watching, in fact, I have to watch the score to get any idea.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2013

It must be mostly a matter of what we grew up with. I grew up with baseball, cats, and lasagna. Other people prefer football, dogs, and pork chops. Tolerance is the only answer, I guess. (Unless they like soccer, snakes, and guacamole. We have to draw the line somewhere.)

LikeLike

office of surrealist investigations

February 7, 2013

Love the baseball recollections and coming from a hockey-crazed nation I see that game as only slightly inferior. Though trying to explain a balk, infield fly or a consistent strike zone makes for more complex discussions than trying to explain hockey offsides. Just as when you were a kid, keep ignoring the salaries and simply enjoy the game, you can still get in to see the game live for cheap. Would love to see the return of afternoon World Series games, even if it was only on the weekend. Nothing beats weekday afternoon ballgame pushing work and distractions aside for a few hours.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2013

I’ve never understood the balk rule, and I suspect many of the players don’t either. It’s one of those things that can change the outcome of a game, and almost nobody saw what happened.

I agree with you about afternoon baseball — it’s like a daydream.

LikeLike

Fiona McQuarrie

February 7, 2013

This is wonderful. Thanks!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2013

Thank you, Fiona.

LikeLike

113yearslater

February 7, 2013

Never been a sports fan, except coming from Philadelphia, I had no choice about hockey. I’ve had to just stop paying any attention to it at all. I think my blood pressure dropped 30 points.

Football I never got into. Five seconds of action for every half hour of sitting around … naah. Baseball? Too byzantine. Basketball? NOT ON YOUR LIFE. I went to 12 years of catholic school and the constant excuse to use gym class as coaching sessions for the basketball teams left nerdy, clumsy little me out in the open for years. Hated it then, hate it now.

Anyhow. I’m also not Sicilian. Abruzzese, though — how’s that?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2013

That’s too bad about your gym class experience. I’d think getting someone like you more comfortable and involved in sports would have been the whole point of the class.

Have you been to Italy?

Also, I’d like to read your blog. How do I get in?

LikeLike

susielindau

February 7, 2013

Freshly Pressed!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Way to go!

Just think of how many had to run out to the store for more chips after the lights went out! I think Frito-Lay had something to do with it….

I have to admit that although I love playing baseball, it is too boring to watch more than once a week. …I know I will get knuckle punched for that one…..

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2013

No knuckle punches from me, Susie. It has become boring. A baseball game shouldn’t last four hours unless it’s gone well into extra innings. Too many commercials, and way too much posturing and fidgeting and calling time.

LikeLike

Wyrd Smythe

February 8, 2013

Do you watch games that are shown after they are played? When I watch live, they run about 3 hours depending on the pace of the game. A game that goes really fast lasts about 2.5 hours, but a longer game can maybe go 3.5 hours.

A lot has to do with the pace of the pitcher. Some have so much delay built into their business they earn the nickname “human rain delay.” If a pitcher is doing badly and is getting a lot of mound visits, that’ll slow down a game.

It’s when a 13-inning game approaches the 5-hour mark that one starts getting really restless. Let’s end this thing and go home! (Still, that’s one of the cool things about baseball to me: no clock.)

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2013

I don’t watch that many games anymore. I used to try to watch baseball with my son, thinking it was a good way for him to learn. That was back when I still stupidly believed he would ever listen to anything I said.

The two things that drive me a little crazy are the batter constantly stepping out of the box to go through his readjustment routine and the manager changing pitchers three times in an inning. I never watch games that have already been played. Do you record games?

LikeLike

Wyrd Smythe

February 9, 2013

My ignorant theory is you can only expose kids to as many things as possible and see what sticks. There were serious comprehension gaps between my parents and I (they couldn’t quite fathom their geeky (adopted!) son), but I will give them huge credit for offering me so many different things to explore over the years.

They really tried to cover the range: coin and stamp collecting to crystal radios to weekly visits to the library (our only “internet” back then), to geeky gifts from the Edmunds Scientific catalog. Actually, not many stuck, but some stuck for a lifetime; they became lifelong friends. Some became foundation elements in what became my career.

So you never know. They may not seem to listen, they may not admit they listen, but I think they do.

I’ve been told those cups are a real (but oh so necessary) pain to wear, hence all the adjusting. It’s the spitting that wears on my nerves. It’s mostly sunflower seeds and bubble gum these days, but I do not understand the need for all the spitting.

(At the end of a game, the piles of sunflower seed shells around the bases and outfield positions are really something!)

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 20, 2013

Trying to “cover the range” is the right approach, I think, as opposed to forcing a kid to take piano lessons or play basketball. And I agree about the spitting, but sunflower seed shells are better than tobacco juice.

LikeLike

Wyrd Smythe

February 20, 2013

MUCH better than tobacco!!

I’m one of those who was forced to take piano (from my music teacher mom). I’m glad that happened; it gave me the gift of music, and that lasted a lifetime. Being able to play has been a great comfort and joy throughout my life. You meet many people who say they wish their parents had forced them to learn (or continue learning) an instrument. You don’t meet many who say they are so glad they dodged that bullet.

Sports, no doubt, have value, but music and literacy are gifts that give back an enormous amount over a lifetime. I’m totally down with forcing kids to learn these. I’d throw in some maths as well, since a foundation of numeracy can be very useful when someone tries to fool you with numbers or stats!

LikeLike

113yearslater

February 7, 2013

BTW, ever seen a cricket game? You want weird. I was in Wales one time slouching on a friend’s couch with the TV on showing a cricket game. There was all these numbers on the screen. She was in the kitchen and called out, “What’s the score?”

I couldn’t tell. I swear to you, I looked at all those numbers, and I couldn’t tell. There was one set of numbers that said something like 382-86 or something. I figured that wasn’t it. Maybe it was a serial number or something.

It was the score. The score was 382-86. Jesus.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2013

I wrote a post partly about cricket a couple of years ago. It was a dialogue I had with a fellow blogger who lives in India.

LikeLike

segmation

February 7, 2013

I am so amazed that the Super Bowl is a national holiday here in the US. Amazing isn’t it?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2013

That may be exaggerating slightly, but it’s close to a national holiday.

LikeLike

segmation

February 8, 2013

No national holiday too me! Sorry! http://www.segmation.wordpress.com

LikeLike

arzainal

February 7, 2013

Reblogged this on ARZcreation.com.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2013

Thank you.

LikeLike

arzainal

February 8, 2013

Welcome

LikeLike

Do I Have My Keys?

February 7, 2013

I hate watching baseball. I can’t help but think how much these athletes get paid to spend such a hefty chunk of their time on defense simply standing in the grass, waiting for the ball to make its way in their direction. At home plate, I feel like I’m staring at two guys playing catch while someone else tries interrupting with a rather large bat.

But, being a Bronxite myself, Yankee Stadium practically had religious connotations attached to its status. My friends agreed it was the only thing in the borough to brag about. I even celebrated the summer I was hired there as a security guard. I appreciated the opportunity to watch the players practice before games and having a great seat once the real action began – memories I will never forget.

Agree to disagree on our choice of sports. But, this post still hits home.

Nice work!

Keep it up!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2013

I agree about the salaries, but what about the guy who comes into a football game two or three times to kick a field goal?

That must have been fun working at the Stadium. Have you blogged about that? Where in the Bronx did you live?

Thanks for the kind words. I appreciate it.

LikeLike

Do I Have My Keys?

February 8, 2013

Haha.

I never consider the kickers in football.

Working at the stadium had its moments. Unfortunately, my time there was cut short due to Multiple Sclerosis. I got to enjoy about a month’s worth of work. My first day was the All Star Game! It actually went into extra innings. I stood on my feet for about 12 hours. Never blogged about it, though. Maybe I will one day.

I still reside in the Bronx – Hunts Point. I was raised in the University Heights section, though.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 9, 2013

I’m sorry to hear about the MS — I hope you’re doing well.

I went to Fordham University, by the way, and still miss those lunchtime trips to Arthur Avenue.

LikeLike

Do I Have My Keys?

February 9, 2013

Ah. Yes. Little Italy.

Thanks for the well wishes!

LikeLike

alanamorgan2012

February 7, 2013

Well said. I am an american from Boston with an Australian other half which should mean that i love ALL SPORTS. The reality is I love BASEBALL. I tolerate basketball when people can actually play the game. I hate American football because of the excessive padding, pandering to commercials and general uselessness with 900 people on various “special teams.” Hockey? Used to love it but they’ve gone on strike so much I can’t be bothered. Soccer/football-to-everyone-else…meh. Rugby, I respect (anything that recommends taping your ears to the side of your head seems to be good to me, plus the best drinking toast I learned from a rugby team). Cricket, I’m trying to understand because of aforementioned other half, but Australian Rules Football I’m all in…anyway….that’s where I stand 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2013

I watched a game once — I think it was called hurling — that was brutal. At one point, a guy was lying on the field injured and they didn’t stop the game. They just kept playing, and literally ran right over him. No padding.

I’m with you on baseball.

Thanks, Alana.

LikeLike

Madge Madigan

February 8, 2013

Nice to be reminded of a simpler time. Thanks, nice write!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 8, 2013

Thank you, Madge. I’m glad you liked it.

LikeLike

Bruce

February 8, 2013

I love the second cartoon, needing 20 secs injury time-out. And remembering standing and cheering about something. Classic.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 9, 2013

There was at least one other incident, Bruce. The Mets had the bases loaded and, with their best hitter coming up, I left to get something to eat. While I was standing on line at the concession stand, I heard the crowd go crazy and I immediately knew I’d missed seeing a grand slam. They didn’t have instant replay at the ballpark back then.

LikeLike

Bruce

February 9, 2013

Frustrating for sure, but a memory all the same. It always happens when you aren’t looking. A question for you Charles; when you say standing on line at the concession stand does that mean ‘in line’ (Aussie translation)? Perhaps that’s how it’s said in Canada. Here, it would be in line. I noticed it in another of your posts I think, one where you were standing on line in a bank or Post office or something. I was wondering when I first saw it, if it was an unintentional pun, especially given your post on technology. Bruce

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 9, 2013

I use on line and in line interchangeably. I’ve never really thought about the two variations. In Canada, they say “I was in the line-up,” which really confused me the first time I heard it. I’ll have to do another post about Canadian expressions.

LikeLike

Bruce

February 9, 2013

I look forward to that post.

LikeLike

scribblechic

February 9, 2013

I am an unfortunate collection of uncoordinated limbs, my athletic experiences could be best summed up by the word avoidance. Still, I am not immune to the infectious energy that accompanies attending a sporting event. Your post was a happy reminder of afternoons and evenings spent watching a game, even if in truth I was more likely marveling at the spectators.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 9, 2013

The spectators can be a show in themselves.

Hey, have you ever tried bocce? It’s a great old Italian game that requires no real athletic skill, but just enough effort to justify bragging after a win.

LikeLike

neverphoto

February 9, 2013

I love baseball, myself, and for it’s chess-game approach. Football and other sports have this, too, but the way it is manifested in baseball is like no other. I also love its day-by-day nature with every day counting for something. Nice electric football shot up top, too, btw.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 9, 2013

I’ve never been able to understand how some sports can have that chess-game feature. In hockey, especially, if you don’t know where the puck is going to be, how can you plan a play?

I just finished a brief visit to your blog, and I love those perspective shots, especially the library stacks and the train station.

LikeLike

mostlikelytomarry

February 9, 2013

So happy to see that you were Fresh Pressed again! Congrats.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 11, 2013

Thank you. I always appreciate your kind words.

LikeLike

aynotes

February 10, 2013

Reblogged this on aynotes's Blog.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 11, 2013

I’m glad you liked it enough to reblog. Thanks.

LikeLike

Marusia

February 10, 2013

Congrats on the “Freshly Pressed”! 😀

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 11, 2013

Thanks, Marusia. It’s good to hear from you.

LikeLike

Amiable Amiable

February 16, 2013

I hate football and I dread Super Bowl parties. I always forget that the Super Bowl is upon us until I see the signs of it in the grocery store, then I worry that AA Hubby and I will be invited to watch the game with friends. I’d much rather stay home and blog. We should have a Super Blog, except that it’s pretty challenging trying to eat nachos and type at the same time.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 18, 2013

I forget, too. The older I get, the more unimportant and irrelevant these things become. Now a Super Blog party — that sounds like fun.

LikeLike

Elyse

February 16, 2013

There was magic in baseball when we were kids. Now it’s just multimillionaires in jammies.

My brother had the best collection of baseball cards during that era. We used to play a terrific game, where we’d flip them into a heating grate that went down two floors to our furnace where they burned. Mickey Mantle, Whitey Ford, Sandy Koufax. Sigh.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 18, 2013

I wish you hadn’t told me that, Elyse. I’m going to have nightmares about those baseball cards.

LikeLike

Elyse

February 18, 2013

Sorry Charles. Usually when a guy joins me in my dreams it is a more pleasant experience. Of course, I don’t often mention those cards.

LikeLike

andyhodgson2000

February 16, 2013

I think it’s only a matter of time before people start realising the sports that they love don’t really exist anymore,and stop watching or caring.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 18, 2013

You might be right and it may already be happening. But for every lost fan, the sports probably pick up three new ones — people too young to know the difference.

LikeLike

andyhodgson2000

February 18, 2013

The extra problem, over here in England at least, is that these young would be fans are being priced out of being real fans, tickets and merchandise are just too expensive

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 19, 2013

It’s the same here. I don’t know how a father can afford to take his kids to see a regular-season baseball game anymore. And the playoffs and World Series are priced for the very wealthy, or the very well-connected.

LikeLike

Wyrd Smythe

February 19, 2013

I’ve decided the game itself is better watched on TV anyway. Better visuals, multiple views, replays, commentary, less expensive (and better) food (better beer), and it’s fun seeing the strike zone. Going to the park is nice a few times a year for the experience of being there, but given a decent local sports channel I prefer my easy chair!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 20, 2013

I remember the moment of stunned realization at a Yankee game when I realized I’d just missed some great catch on the field and there was no instant replay. It was just gone. That’s when I understood the seemingly odd behavior of a few fans who sat in their expensive seats with portable TVs on their lap, watching the game they were at.

LikeLike

dancinmoma

February 20, 2013

Wonderful read!! I’m a dance teacher, I have kids and I have to say Baseball is one of my favorites to watch. A simple, yet big moment for my boys was getting their first glove and playing catch with dad, grampa and even great grampa. Mom, too, of course. SO much better than a video game 😉 So in Baseball I call that a “swing and a miss.” 🙂 Following you now ….

LikeLike

bronxboy55

February 20, 2013

How great that your kids’ great-grandfather is still playing baseball. I hope to do the same.

Thank you for the kind words — and good luck with your new blog.

LikeLike

dancinmoma

February 20, 2013

Yep my Grampa (aka great grampa) is turning 97 this month, he’s a World War II vet, plays a great game of catch with his original baseball glove, golfs nine holes and still does his sit-ups every morning! 🙂 Thanks for the words regarding the new blog.

LikeLike