The Mormons came to the door again last night, and I didn’t handle it well. The last time they showed up – several months ago – I invited them in. Maybe I was in a better mood then, or felt sorry for them because it was raining so hard, or because it was late and they looked tired.

The Mormons came to the door again last night, and I didn’t handle it well. The last time they showed up – several months ago – I invited them in. Maybe I was in a better mood then, or felt sorry for them because it was raining so hard, or because it was late and they looked tired.

That evening in the middle of June, we sat in the living room and talked, the two young men and I, they dressed in suits and barely into their twenties, and me in my usual jeans and sweatshirt and now catching glimpses of sixty on the horizon. The conversation was more than civil. It was open and friendly, with both sides explaining their position. They said that God had led them to me, that they had come all the way from Wyoming to deliver a message that would change my life. I told them they must have misunderstood God, or taken a wrong turn somewhere, because they had skipped over a whole lot of people – ten states and two provinces – to get to me, when there seemed little chance I would become convinced of anything.

“It’s nine o’clock at night,” I had said. “It’s raining. You show up at someone’s home, looking like undertakers and wanting to talk about God. That’s weird. Do you see how you’re creating an impression that’s an automatic obstacle, even before you’ve said a word?”

“Yes,” they had answered. “But there’s no other way.”

I served them root beer, and said there had to be another way. We talked, a little about our diverging views, but more about how such disagreements and differences in faith tend to cause big problems. They weren’t going to convert me, and I had no desire to convert them. The Book of Mormon was their lifeboat, and they spoke of it with tears in their eyes. I was sure they would drown without it. But I was just as sure that I couldn’t unravel their faith, even if I’d wanted to. After decades of wrangling with myself and butting heads with others, I’ve concluded that this idea is at the core of everything:

We don’t decide what to believe.

A lot of people will argue with that, and will do so with a passion and certainty that may surpass my own. They can’t help it, because even when discussing belief in general, we all think our convictions have emerged from some process of sifting and analyzing the evidence – that we’ve followed a logical path and reached the only reasonable verdict. Most people seem sure that what they believe is the last step, or at least the latest step, in a series of conscious decisions.

I used to think so, too. That’s what I was taught. It’s a convenient theory, because it holds people accountable for the particular side of the fence on which they find themselves perched. It justifies holy wars, crusades, inquisitions, jihad, and the burning of books and human beings. In fact, if God is in your camp, any endeavor – no matter how unspeakable – becomes sanctioned by its own success. As we all try to understand the incomprehensible, the struggle seems a little easier if we can just get rid of anyone who refuses to follow the crowd. However, the less extreme will settle for changing the minds of those whose faith doesn’t match their own, or those who don’t rely on faith at all.

At one end of the scale we have genocide, based on which culture the victims happened to be born into; we also have threats on the lives of individuals because of a movie they produced, a book they wrote, or a cartoon they drew. At the other end, we have well-meaning visitors showing up uninvited, reciting the scripture that was used to brainwash them, and now hoping to employ that same scripture to cleanse the souls of whoever happens to open the door.

But if I’m right – if we don’t choose what to believe any more than we decide to love opera or despise broccoli – then it’s all a tremendous waste of energy. What we really should be doing is less talking and more listening, building bridges instead of blowing them up, practicing the tolerance every religion professes to cherish. Preaching isn’t going to change anyone’s mind. Threatening them with physical harm or eternal damnation isn’t either. Those things may affect what someone does, or says, because you can coerce through fear and intimidation. But they won’t reach down to the level of belief.

This is written in the Christian Bible: “For by grace you have been saved through faith, and this is not from you; it is the gift of God.” (Ephesians 2:8) In a similar way, Romans 12:3 instructs the reader to “think soberly, each according to the measure of faith that God has apportioned.” In other words, God’s own book teaches that he either gives you the faith or he doesn’t. This isn’t the message being peddled door-to-door, of course, because it undermines the assertion that non-believers will be punished. Why would a loving, all-knowing creator deprive his children of an essential trait, then doom them to everlasting pain for it? He wouldn’t. Further, if heaven offers the promise of endless joy after death, why would anyone choose to reject it?

That last question, I realize, will be repeated by some. “Yes! That’s what we want to know!” they’ll say, shaking their heads in confusion. Their eyes will flash with genuine concern while their lips curve into a smile that says, “You poor idiot. I have the answer right here. I’m going to heaven and you can come too, if you’ll just wise up, and believe.”

Believe? Or say I believe? They’re not the same things, and if it’s true that God exists and hears my thoughts, I’d be fooling everyone except the only one who matters.

I don’t think a single person or group holds the answer. We’re all born into a pool of principles, or we fall into one, modifying our belief systems gradually, bit by bit, through experience. But the possession or lack of faith is beyond our control. It isn’t a choice. In this sense, all religions are equally valid, and equally useless. Each is no closer or farther from the truth than the convictions of atheists, the uncertainty of agnostics, or the philosophy held by anyone else.

It was a pleasant place for my mind to be, this cloud of shared ignorance, a feeling of tolerance, empathy, and peace. We could all get along.

Then the Mormons came back.

These were not the same young men who had visited during the summer. Those two had called me twice in August, wanting to know when we might meet again. I had told them that circumstances in my life had changed, and I no longer had the motivation to continue our discussion. Now two different well-dressed, smiling people were standing there in the dark. They’re sending in the SWAT team, I thought.

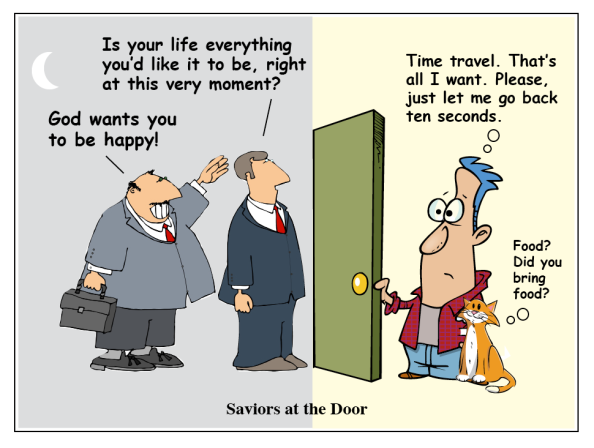

“God wants you to be happy,” they said. It was the smiles that bothered me.

“How old are you?” I asked them. I knew that had nothing to do with anything, but I said it anyway, as though it did.

“Twenty.”

“Well, I’m almost fifty-seven. I’ve read shelves of books on this subject. I’ve talked and listened to hundreds of people – preachers, evangelists, scientists, non-believers. What are you going to tell me that I haven’t already heard? Do you have some late-breaking news about Jesus?”

That’s pretty much what I said. Later, after I closed the door and sent them back into the night, I wished I’d said this:

“If the ultimate goal is to understand how we got here and what our role might be, we’re all at square one. Nobody knows what they’re talking about, and that should tie us together, not tear us apart. Let’s try to figure out how to do that. Would you like some root beer?”

I’d been given the chance to extinguish a small fire, but instead I had started another one. It’s the collection of such incidents that has led to the conflagration the world now lives with. All based on an inability – or refusal – to listen and accept.

At the same time, understanding and respect may be too much to hope for, and wishing we could all get along is as simplistic as saying that God wants us to be happy. Maybe tolerance is the best we can do. If we could manage to avoid killing people in the name of religion, and stop vandalizing churches, temples, and mosques, that would be a great beginning. Simply leaving each other alone would be an improvement.

Wherever we are along the spectrum of faith, it should be a private matter, and a humble one. When we insist on turning it into a show, an excuse to behave badly, or a reason to do battle, we defeat the purpose.

At least, that’s what I believe.

Val

October 12, 2012

You’re very brave to have posted this four-parter, Charles. I wouldn’t have done it, even if I could. I tend to leave religion and politics to other people, not because I have no viewpoints, but simply because I prefer a quiet life.

I personally think that we, as human beings, just haven’t climbed high enough up the evolutionary ladder to all get on with each other. And I think it’s that which is at the heart of our inability to get along with each other and tolerate each other.

As for the Mormons and others inclined to visit with their sermons at the ready, I just politely ask them to go away. If I’d wanted them there, I’d have invited them, and I didn’t.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 13, 2012

Your last sentence is the point, really. The conversations are often obnoxious because they’re unsolicited and one-sided. The implicit message is that what they believe has ultimate value, and what I believe is dismissed as irrelevant. Communication, which should be their primary goal, doesn’t take place under those circumstances.

LikeLike

Val

October 13, 2012

There was one occasion that a JW (Jehovah’s Witness) rang the doorbell. I stopped him and said that I was happy with what I already believed (though I didn’t say what it was – or wasn’t) and then I commented on his accent and asked him where he was from as he didn’t sound Welsh. He told me he was from London which was where I was born, and we got chatting about his past and his family. We had a delightful conversation that was not to do with religion at all. At that time, we connected. So… maybe there’s a moral in that or something?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 13, 2012

It seems to prove, again, that both sides have to be open-minded and listening. The reflex reaction of most people — usually mine included — is to get rid of the uninvited visitor as quickly as possible.

LikeLike

cat

October 12, 2012

Excellent write, my friend … I am so glad you wrote about it the way you did … it’s one thing to preach any belief, but it’s another thing when it comes to living it.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 13, 2012

Thank you, cat. I hope I managed to get my message across somewhere in those five thousand words. As I tried to convey, I’m still not practicing what I preach. But I’ll keep trying.

LikeLike

creatingreciprocity

October 12, 2012

You may have already seen this, Charles – but just in case you haven’t – http://www.ted.com/talks/karen_armstrong_makes_her_ted_prize_wish_the_charter_for_compassion.html

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 13, 2012

I hadn’t seen that lecture, Trisha, so thank you for sending it. I don’t know if I agree with her that it’s time to move past tolerance, to compassion. Have we reached tolerance yet?

LikeLike

creatingreciprocity

October 14, 2012

I know what you mean about tolerance, Charles, at best we have probably achieved a veneer of tolerance. Maybe it isn’t a destination, though? Maybe it’s just a short stop on the way to being happy that we are all different and learning to work out the problems in that? I don’t know – but then again like Socrates, the older I get the more I realise that I know practically nothing! I liked your series very much, though – at least I know that!

LikeLike

Diane Henders

October 12, 2012

I’ve thoroughly enjoyed this series, Charles! It’s been fascinating to hear your views and follow your thought process. As Val says, you’re brave to tackle this topic.

I came to the conclusion long ago that 99% of the people in the world fall into two camps: Those who are certain they belong to the “right” religion and want to change everyone else’s thinking to match their own, and those who are searching for the “right” religion. There’s no point in talking to the first group, and I’m certainly not qualified to advise the second group, so I just don’t discuss religion.

The final 1% are critical thinkers like you – virtually impossible to find, but worth their weight in gold. 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 13, 2012

Thanks, Diane. That’s nice to hear, because while I think we need to somehow rise above the level of debate, I have no idea how to do it. I guess we have to begin by wanting to.

LikeLike

The Sandwich Lady

October 12, 2012

Some of the most “christian” people I know are not Christians…they are Jews, agnostics, even atheists. I don’t think religion, particularly any one religion, is a prerequisite for salvation. Those I admire the most are the “casserole Catholics,” (who don’t even need to be Catholic), who quietly live their faith without talking about it, and who turn up on your doorstep with a casserole rather than a sermon when you are going through hard times. Thanks for a great post.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 13, 2012

And thanks for a great comment, Catherine. I’m with you: I always try to pay less attention to what people are saying and look closely at what they do. Those who show compassion and support for their fellow human beings rarely have time to preach.

LikeLike

Stacie Chadwick

October 12, 2012

This is a brilliantly written essay, my favorite of the four you’ve posted.

A friend of mine, who was recently trying to buy a house in an increasingly tight market, sent out an email asking for people to “pray for her” to get the house she wanted. It wasn’t a sentiment based on need, only desire. It really bothered me.

Another friend in an MBA program recently created an anonymous survey weighing factors such as education, political leanings, and income against a belief in God. I’m incredibly curious to see the results. I have a feeling that I know what they are already (a miracle!).

Thanks for a thoughtful jumpstart to my weekend, Charles.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 13, 2012

Stacie, I was once in the car with a friend and as we were about to pull into a crowded parking lot, she began to pray out loud, asking Jesus to provide her with a parking space. I could only try to imagine what would have to happen in order for that to work — for example, was she hoping Jesus would make someone else’s car disappear? Or did she want him to create a new space out of thin air? I never asked her.

We all have a large collection of ideas and beliefs in our heads, and a limited amount of time to investigate those ideas and beliefs. I think, out of necessity, we identify certain areas in which we’re willing to be lazy, choosing to spend less of our time thinking and questioning. It is strange, though, how so many of us will devote more time and energy to relatively trivial matters, and less to the bigger issues of life.

LikeLike

mimi torchia boothby

October 12, 2012

yeah, God gave my healthy husband cancer and killed him too. And yes, lots of people prayed fervently for his recovery. Good series, thanks for opening the door.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 14, 2012

I’m sorry to hear about your husband, Mimi. Most of the religious people I know would tell you that God plays no role in afflicting people with fatal diseases, although they do give him credit for the occasional miraculous recovery. I understand the comfort people must feel when they can put a difficult situation into God’s hands, but praying for him to change his plan doesn’t make any sense to me.

LikeLike

dearrosie

October 12, 2012

Bravissimo for an interesting thought-provoking series. I don’t know anyone else who’d invite Mormon kids into their home for a chat and a root beer.

My Mother was the most religious person I know, but she lived her faith quietly. You’d never hear her proselytizing – even when her children disappointed her by not being at all religious.

[ I just did a google search to check the spelling of “bravissimo” and discovered that “Bravissimo is both an Italian word used to express highest praise, and a lingerie retailer that provides lingerie and swimwear in D+ cup sizes.” You know what I meant. ]

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 14, 2012

Faith seems to be stitched together from pieces of evidence, perceptions, intuition, experience, tradition, and the periodic leap that people make for reasons they cannot explain. And then there’s the element of timing. The mystery for me, then, is how one person can expect to convince anyone else to arrive at the same kind of faith just by talking about it.

You’ve written about your mother on your blog, so I already knew she was a special person. Thank you for this additional insight, Rosie. I’m sure she was proud of you.

I’d never heard of Bravissimo lingerie. It does sound like a good name for a gelato company, though.

LikeLike

dearrosie

October 14, 2012

My Mom was proud of me even though I’m sure I disappointed her by not being interested in religion. Thanks for remembering her. (((sigh)))

Talking of gelato we were in Malibu yesterday and of course our steps led us to our fave ice cream store. I always think of you when I go there. 🙂

LikeLike

patricemj

October 12, 2012

I enjoyed this series a lot. Part of me wondered why you had closed the comment section, but my sense was it was a necessary choice. Sometimes it’s difficult to get one’s truth out, or one’s version of the truth, while also fielding responses. To me, this was some of your most engaging writing. It made me late for work 😉

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 14, 2012

It would have been hard to respond to comments on one post while trying to write the next one.

Thanks for your feedback, Patrice. It means a lot to me.

LikeLike

Musicforkids

October 12, 2012

Very nice! I have struggled between being very pissed off at Christians/Mormons, etc. and trying to figure out how to tolerate them and realize we are all connected deep down. Your essay helps to clarify the “connected” part. I do believe that your conclusion of faith being a private matter is the way to go.

Life is extremely interesting, life is engaging and awesome and deserves our respect. It is what it is and that doesn’t make it any less beautiful. In fact, that’s what makes life beautiful. Without the war, destruction and suffering there would be no fire. If there’s no fire there’s no passion. If there’s no passion there’s no life! So maybe it’s all okay. The life and death struggle is ultimately what keeps us engaged. And whether we participate in it through a passionate religious war or wait until our “time” has come we all struggle with it and honestly face it in the end.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 14, 2012

If there is a God and he’s involved in our life on Earth, I’d imagine war would be one of his greatest disappointments. I can’t think of anything more unreligious than complete strangers killing each other just because their government or their religious leaders told them to.

LikeLike

She's a Maineiac

October 12, 2012

Your last paragraph perfectly sums up how I’ve always felt.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 14, 2012

It was a long trip to get to that last paragraph, wasn’t it? Maybe I should’ve started there.

Thanks for the comment, Darla. I hope things are going well for you.

LikeLike

Ashley

October 12, 2012

Charles, I understand the fact that we are on a different belief journey. This particular Christian appreciates that you were respectful to those of us who do believe. Beautifully honest blog.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 14, 2012

Thank you, Ashley. I’m glad you saw it that way.

LikeLike

Anonymous

October 12, 2012

I went to a Private- Catholic School until college. It wasn’t until I was no longer around religion that I began to question it. When I was young I was a very religious student with a passion for my spirituality. I now, maintain that same passion for my spirituality with my own voice and my own set of beliefs. I do not wish you to believe what I do because you have not lived my journey and I would be depriving you of yours.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 15, 2012

Well said. Thank you for that.

LikeLike

marymtf

October 12, 2012

I’ve had Seventh Day Adventists come to my door. I did not invite them in for a chat. I know no-one who has. I knew from the outset that I wasn’t going to hear anything earth shattering and did not want to encourage them, theirs is a thankless task as it is.

I only know you through your posts, Charles, but they consistently mark you out as a nice human being, and kind. I can only think you must have been going through some sort of phase that had you at least willing to hear what these men had to say even if you were never going to be convinced. Having heard them out you didn’t want to encourage a second visit.

I’m sorry to disagree, but we do decide what to believe. Not as children maybe, and that’s why we need to be most careful with our impressionable darlings. There may have been a time when we lived and died believing implicitly in whatever religion we were born into. I understand atheists and agnostics (although they too are sure they are right and not tolerant of the rest of us) but I don’t get people who convert from one religion to another. You either believe in God, (and I don’t mean only the Judeo-Christian God) or you don’t. What does converting do for those people? Is it that the other religion is prettier or it offers more security or makes you feel superior to the rest? I think it’s less to do with ‘my-God is better than your God’ and more about the grass being greener. Or maybe not. As for ‘less talk and more listening’, I agree. Individually many of us are aware. We have all said it at one time or another, but as a group, we’re getting further and further away from that. I’m finding it dispiriting as I’m sure you are.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 15, 2012

Dispiriting, but not hopeless. I think all it would take is for people to stop saying “I’m right and you’re wrong” and simply start saying things like, “This is what I believe” and “I’d like to know what you believe and how that helps you in your life.” I agree that atheists are just as sure as devoutly religious people, but I don’t know any agnostics who are intolerant. An agnostic — like a skeptic — isn’t incapable of believing; it’s just that pure faith isn’t enough.

Thank you for your kind words, Mary. I think we could have some interesting conversations about this, and somehow be supportive of each other at the same time. It shouldn’t be that difficult.

LikeLike

James

October 13, 2012

I did this also in a moment of weakness, I am not a man of faith by choice but was getting tired of the constant door knockers so I invited them in and spent two hours having a civilised argument where they were making what seemed to me bold statments and then I would challenge them with logic and after a while they gave up and left. I thanked them for their time but I must admit I enjoyed the whole thing. Funny I havent seen them for some time now.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 15, 2012

James, I think the problems occur when one side or the other is disrespectful. Differing views, sincerely held and expressed, can be instructive for both. But polite disagreement is probably a rare experience for these visitors.

LikeLike

Bruce

October 13, 2012

I enjoyed the lot of it, except the death of your Godparent’s son. That set the tone for the rest and what an excellent read. Incredibly brave, talking about religion and boy, didn’t you cover a heap of topics to expand upon. I had the impression from the start (could be wrong of course) that you have been saving this for a long time and perhaps something recent became the catalyst for your words. There are so many things you cover and your words serve to remind me of days past and thoughts that faded, or stayed. Bruce

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 15, 2012

I never did find out why my godparents’ son was killed, but I assume it had something to do with drugs. I had been considering this topic for a long time, Bruce, and put it off as long as I could. I’m glad you took the time to read it, and got something out of it, as well. Thank you for saying so.

LikeLike

Michelle Gillies

October 13, 2012

Charles, this was a brilliant series. Thought provoking and engaging. I intend to read it again from beginning to end.

I worked for a TV station that had a “religious” license. Legally they were to represent all faiths. It was an eye opener, I have to say.

I am a Christian and I have a very strong faith. I was given a very strong foundation to build on. That came from my Mother who taught more by example than by words. Our house was always filled with love for everyone. If someone was hungry they got fed. If someone was cold they got clothed. If someone was sad they got hugged. I grew up with Jewish people in my life, black people in my life and handicapped people in my life and was never taught that any one of them was any different than me. I was 12 when my Mother passed and for a time my younger sister & I spent time in the system. That is when I learned that my black friend was black and that it wasn’t appropriate for us to be friends. That is when I learned that sweet Jeanie who was dropped as a child was actually a retarded adult. I think you get the idea. I thank God every day that my Mother gave me that strong foundation and that I never lost it.

When I went to that religious station it was just like that twelve year old girl being dropped in the system. I learned things I didn’t want or need to know. On my own I discovered that pretty much every faith has bad, hurtful and evil people representing it and occasionally you run into someone I like to call “the genuine article”. I left there quite battered, bruised and scarred on the faith issue and seldom talk religion with anyone now. I still believe and wouldn’t want a life with no faith in it. One of the last things I did at the station was running an “I believe” campaign. There were bracelets and signs etc. that simply stated “I believe…” the rest of the message was “…you fill in the blank. I won an award for the campaign but, the real reward was that it was the only time I ever got everyone in the building to agree on a campaign. It was not a magic fix by any means but it opened some dialogue.

Thank you for such well thought out and honest series. It is appreciated.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 15, 2012

I think you should write a book. Have you ever thought about it?

LikeLike

Michelle Gillies

October 15, 2012

I am curious what would prompt you to ask that?

I have had people tell me I should. I have had people ask me if they could.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 16, 2012

It seems as though you’ve been on an amazing journey, and I think a lot of people would be interested in reading about it.

LikeLike

Michelle Gillies

October 16, 2012

That puzzles me. I can’t imagine why people would be interested. I haven’t had a big life and there are a lot of people out there that have more interesting tales to tell. I think it is perspective. I thought a lot of things were “normal” when I was living them.

If I am honest, there are some things that if written about would only hurt people (no matter how hard I try to make light of it). That has always been my wall.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 17, 2012

I understand, especially about that last part.

LikeLike

Michelle Gillies

October 17, 2012

How do you get over that wall?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 18, 2012

I guess it depends on the circumstances, but it eventually has to come down to a decision: Do I want to write the truth, or at least what I believe to be the truth, or do I want to spare feelings and avoid embarrassment? It’s usually messier and less clear than that, of course, but those are the basic criteria. One option is to write the book as a novel, rather than a memoir, although that approach can have its own dangers.

LikeLike

Sybil

October 13, 2012

The last time we had Mormons at the door I squealed to my daughter, “We’ve got Mormons!” She just loves chatting up Mormons — it’s almost a sport with her.

BTW have you listened to the Musical “The Book of Mormon” ? Funny and yet respectful.

I love it on “Survivor” when folks start thanking God for helping them win a challenge or looking all puzzled when HE didn’t help them win.

You’re a thoughtful guy.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 16, 2012

I like talking to them, too, as well as the Jehovah’s Witnesses. But the timing has to be right, and it rarely is.

I’ve seen a little of that musical. I wonder if there were protests.

LikeLike

Jac

October 13, 2012

Your last paragraph was the best, and unfortunately, too many people DO use their faith as an excuse to behave badly or to force it upon others. Human nature tends to take all things, good and bad, and use them to further their own agenda. We are selfish little beings, like babies who want what we want, when we want it, to feel good. It’s a shame. I have come to the conclusion that there are 2 types of people in regard to belief in a superior being. Ones who want to believe and ones who don’t. Those who want to, are seeking someone to help them, guide them, protect them, in this crazy world. It’s a form of humility. Those who don’t want to believe, just really don’t want anyone to tell them what to do or how to do it. It’s a form of independence. I am not saying one is better than the other, because within each category is also good and bad.

Here is my outlook in a nutshell: I can’t possibly believe in evolution (w/o a Creator) because there are just too many amazing creatures, too much beauty, too much synchronization of life forms, to say that it all came about by chance. That leaves the idea of a creative, all knowing intelligence, who in essence, is our Father by the mere fact that we all came from the original design. So I give to Him as much (really, way more) respect as I gave to my own eartly father, knowing that everything he taught me, was done out of love for me. I take His teachings and guidance eagerly, knowing that He only wants the best for me, as His love is so unconditional (though He will correct and admonish, also for my good). I see my faith as a blessing, an honor, a privilege and a responsibility, to pass it on, but never to hurt anyone with it. I also don’t see it as a way to reap a reward after I die. I see it as the least that I can do for a Creator who is all loving, all merciful and Who was willing to sacrifice so much for one little soul like me. Why would I not want to spend an eternity with One like Him?

I try to be like St. Francis, who said “preach the Gospel at all times; when necessary, use words”

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 16, 2012

I still say it’s beyond comprehension — with or without a creator. I think the magnitude of the mystery leaves us all off-balance, and we tip in one direction or the other with little or no control over where we land. Even if I can imagine a being powerful enough to have brought the universe (and life) into existence, it’s still a leap to arrive at any detailed belief system. On the other hand, as an agnostic, I can appreciate the attempt all religions make to understand and answer the big questions. It’s the hostility that makes no sense to me. As for evolution, I wanted to end up discussing that, but never got there. Maybe another post, another time. Meanwhile, it makes me happy to know that your faith brings you so much comfort, and that you treat people with such generosity and love. Catholicism helps you be the best person you can possibly be, and I think that’s what religion is really all about.

LikeLike

Jac

October 16, 2012

Of course it really is beyond comprehension, and if I seemed to imply that I understood it all, then I was remiss. What I can safely say is that we all have some kind of belief system (even unbelief is a belief!) and to me, Catholicism answers more questions than it leaves. I totally agree that hostility makes no sense in this realm. When ones finds something that they love and gives them hope and peace, the last thing they should project is hostility. This is where the evil being comes into play, but that’s another conversation altogether!

LikeLike

earthriderjudyberman

October 14, 2012

Charles, I have read all your thoughtful posts on this subject. I agree with you on the need to build bridges instead of walls. I have looked into other faiths. There may be more than one path, but I am happy with the one I chose. I do believe I did. I might not have a lock on faith. It’s just enough for me that I believe in the basic tenets that all major religions believe: The Golden Rule. Treat others as you want to be treated.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 16, 2012

I think that’s what it all comes down to, Judy. And it’s what makes the hatred and violence seem so incongruous.

LikeLike

Nectarfizz

October 14, 2012

Dear Charles, I think the only way to really see faith is to know what faith is for you. For me faith has never been about proving I believe in something. Never needing to go and tell others what I know. To me faith is knowing something and feeling that it’s perfectly ok not to share it. To accept that “this person has some beliefs I don’t” and being perfectly fine with it, so long as that guy was kind and good to others and never tried to tell me what I should do or believe either. I think real faith is trusting that there is good. There is love and there is sunlight and there is at the end of all the crap, someone who does what is needing done, for the simple reason that it is the right thing to do. Is that God? I don’t care if it is. What I care about is being that person who sees what needs to be done, and does it..because I trust that out there is someone who will see me doing it and think “I need to do what needs to be done, because it is the right thing to do…just like that woman over there” I know that there are some who revel in their faith. It always just seemed like bragging to me. I am more interested in learning what makes the wind sigh in my face. What makes Christmas lights so damned alluring when I am lying on my back under the tree. Why people touch each other and need to be held. My faith is in mankind. There is the true religion. There is the true faith. It is believing at the end of all the talking there is a hug waiting to be given and a hand waiting to be held. Is that God? Some would say it is..but I don’t care. All I care about is being the one holding out my hand and giving that hug because in the end of it all…whoever is there at the end will not care about anything I said. It is what I did with my heart that he will notice and comment on. There is no such thing as perfect religion, but there is such a thing as love. My religion is that which all men and women need and unconsciously seek all their lives to find…Love. Love you Charles..don’t tell me you believe in God..tell me you believe in love..and we will get along well forever.

Bekki

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 16, 2012

I think we will get along just fine, Bekki. If everyone saw things the way you do, there would be plenty of room for all kinds of belief — and the differences wouldn’t be a problem, but rather an important part of what keeps people talking, listening, and supporting each other. It seems possible, but I don’t know how we’ll ever get from here to there. I guess we each need to just live that attitude individually, and hope it catches on.

LikeLike

writingfeemail

October 14, 2012

Mormon kids get their college tuition paid by the Mormon Church if they ‘work’ the faith and go about the world in their adultwear looking all proper. If they would pay for my kid’s college, I’d do it too. That’s why they come out in droves – it’s a small price to pay.

Or is it?

My husband nearly ran over two women who were walking down our driveway in the center of the drive. In fairness, we live on a mountain. Our driveway is l-o-n-g and it goes straight down, across a creek, and then steeply back up again. It is lined with overgrown pines that we are in the process of cutting back, but at the time shaded it into darkness even mid-day.

Who thought it would be a good idea to send these two young women into such a place? I say, call first. We’ll let you know when it’s a good time to visit and even drive over to the road and pick you up!

Safety must come first. Not everyone is a law abiding citizen – unfortunately.

As for what to believe – I have been blessed with a multi-religious set of relatives and friends. My grandfather, a Baptist by birth, spent time with the Mormons in Utah and I grew up with the Book of Mormon next to the King James Bible. In his handwriting verses were highlighted that coincided with each other. Never once did he take time to look for the differences.

My cousins were Catholic. I visited with a group who studied Meher Baba (may be mispelling that – it’s been a long time). They had an educational temple at Myrtle Beach.

We camped at Cherokee nearly every other weekend. My father loved it. Of course that meant we were absent from our church every other Sunday. But those campfire meetings and the Native American chants and dances were closer to God than anything I’d ever experienced inside four walls.

We were Methodist by Church choice and our leaders often took us around to other churches to see how they conducted their services as a way to grow in ideas.

I am only now realizing how beneficial it all was. We were and are spiritual instead of religious. We respect other’s faiths and as an adult I have made friends with Buddhists and Hindus and Jews, etc.

What do I believe? I believe in a Higher Being that dwells inside of us all. The word for God is Dio in another language, but the spirit is the same.

I know this is an abnormally long comment. But it’s been waiting since Part 1. LOL.

Thanks for the space and for your absolute tolerance. By questioning we learn more than blind faith alone.

LikeLike

1of10boyz

October 15, 2012

Sorry to inform you that the Mormon’s don’t get much in college tuition for doing their church service (missions), unless it is a scholarship and those aren’t any different that the rest of the world; some people get them and most people don’t.

The desire to share as a Mormon is not about the big scary world we go off into, but about finding in ourselves in the religion we believe. The desire to teach and to share cause the teach to learn, that new knowledge should help survive the struggles and challenges that will most certainly be experienced in later life.

That foundation of selfless service for 18 months or 2 years good men and women into better men and women that can help create strong families.

My experience has been that the guy sharing the rootbeer and an opportunity to talk was as fulfilling as the family/person that really was looking for religion. I learned much from both of those experiences that shaped who I am today.I met many more that just wanted to talk about life than I did that were looking for a change or a religion but in the process I learned more about ME and my religion than anything I could have hoped to share with the others I met.

I have often thought my mission wasn’t about converting anyone but ME. The others I helped were really icing on the cake of discovering in ME what I needed and what I should do, and how religion could play a role in my life.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 17, 2012

10fof10boyz, you’ve given me more motivation to respond better to unexpected visitors from now on. Thank you.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 17, 2012

I enjoyed reading that slice of your story, Renee (writingfeemail). The variety of your experiences seems so much richer and more exciting than the typical indoctrination that many kids grow up with. As for the Mormons, the two I spent time with told me that they had to pay all their expenses, including travel, housing, transportation, and food. They didn’t mention any financial benefits coming their way, and I found myself asking where they were coming up with that kind of money at their young ages — especially since they seemed to be spending all their time calling on people and no time at all working to earn a living. Their explanation was that they’d put their trust in God to provide what they needed and lead them to where He wanted them to go. I agree with you about the safety concerns. Now I’m wondering how many of these young proselytizers end up in dangerous situations. Neither of us ever really knows who’s on the other side of that door.

LikeLike

Nectarfizz

October 18, 2012

I agree with you. One of the reasons I am so accepting now is how many differing religions I had surrounding me all my life. My grandmother was Catholic, my father was Presbyterian and my ex husband Pentecostal. My step-sister was half Jewish my M is Atheist and I am Taoist. What a weird concoction to draw knowledge from and yet it helped me know who I am and what I believe in.

LikeLike

Sandra Parsons

October 14, 2012

I grew up in an atmosphere of love, faith and tolerance… without ever hearing the word god. Later I read the bible and the koran out of curiosity, and they were just like other story books for me, mildly educational. I cannot think of a single thing that is missing in my life because I am not religious, but I don’t blame anyone who believes in other things than I. I guess on a subconscious level I agree with you that no-one really decides willingly what to believe.

What strikes me as worth thinking about is the fact that you will never meet an atheist who comes to your door and tries to convince you to convert to his set of beliefs. Why is it that certain religions feel the need to invade your home and tell you that you are living your life the wrong way. Not very respectful or tolerant I’d say. The more I admire your effort to treat such people with kindness, I wish I was this mature yet.

Thanks for another thought-provoking series of posts, for me it could have been longer 😉

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 17, 2012

I get upset when religious people try to portray non-believers as immoral, or members of other faiths as evil. It’s just more narrow-minded, Us-against-Them thinking, and is sure to make matters worse. By the way, I suspect you’re a lot kinder and more tolerant than you give yourself credit for. (I hope you’re feeling well.)

LikeLike

Sandra Parsons

October 17, 2012

Still well, thank you. As long as I can still read your fabulous posts, and comment 😉

LikeLike

Betty Londergan

October 15, 2012

I find prostelytizing to be one of the most unattractive of all traits and I can’t believe the Mormons send their young men out to do it for 2 years at a time … I guess that’s why so much of the South Pacific is Mormon now — these guys are obedient but they’re not stupid as they mostly end up in some VERY nice places. (Romney served his term in France). I also love your quotes from Scripture. And finally — yeah, I have a really hard time with people who believe that God is responsible and INVESTED in you passing your driving test, landing a particular job, or making that soccer goal. I just really hope that He doesn’t have time to intervene in the particulars of my life –but then again, what’s the difference between hoping for small interventions and praying for the really big ones: like curing a cancer you have?? Do you think that it’s either in for a penny, in for a pound — or what is the magic cut-off point below which He/She won’t deign to get involved?? Even talking about this makes me so uncomfortable because it all starts to sound really lame to believe God is involved in anything we do or feel… but then, I do have faith and do believe … so what does that make me??

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 18, 2012

Luke 12:7 says that all the hairs on your head are numbered. That seems like an incredible waste of infinite knowledge to me. Besides, hair is constantly falling out, and new ones are growing in. God couldn’t be that obsessive-compulsive, could He?

I think your questions make you human, Betty. A thinking human.

LikeLike

rangewriter

October 15, 2012

Charles you have put an incredible amount of thought and work into this series of posts. I hope you are planning to publish them in some more concrete form soon. You express your thoughts so well, with such candor and humility. And I’m always dumbfounded when I learn the journey that some people have endured to come to the place in their beliefs where you are now…one of tolerance to a point, and curiosity to a point, and conviction…of things that are quite different from the convictions that institutions tried to beat into you at a young age.

And the Mormons? (From Wyoming, no less…) I’ve had all sorts of experiences with them and have good friends who are them. But in some cases, if you give them an inch, they’ll take a mile. By getting a foot in the door once, some special red flag must appear on your address so that from then on every fresh-faced young missionary that comes to your region will beeline to your hopeful and friendly door. After several such sessions, civility and tolerance fly out the window and self preservation of your privacy and your personal boundaries is inevitable.

That does not make you a bad person. That just makes you a person pushed to the end of your rope.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 18, 2012

That’s exactly what I was worried about, that by being friendly and open I was exposing myself to endless intrusion. Part of the problem seems to be timing: What are the chances that they’re going to arrive during a moment when I’m not in the middle of something and I feel like discussing their faith and my private life? They always ask if there’s a better time for them to come back, but again, how do I know? From their side, they say that God has led them to me, which seems to suggest that my lame excuses are meaningless and that I should drop whatever I’m doing and invite them in. Which is probably what I’ll do the next time.

Thanks for the great comment, Linda, and for your consistent encouragement. It means a lot.

LikeLike

rangewriter

October 18, 2012

Charles, if you actually drop what you’re doing next time and invite them in for a listen, I would rank you as the ultimate epitome of tolerance and open curiosity. I’d put you right there beside the Dalai Lama!

LikeLike

Anonymous

October 16, 2012

Nicely said, Charles. As always. Tolerance and respect would definitly be a start…

By the way how is your daughter doing? Does she enjoy her marriage? Read from you soon. Allyson

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 18, 2012

Thanks, Allyson. Tolerance, respect, and a little compassion would definitely go a long way.

My daughter is doing very well. She just started a teaching job, and is enjoying her marriage and her new home. Thanks for asking.

LikeLike

amelie

October 16, 2012

I’d been given the chance to extinguish a small fire, but instead I had started another one.

Yes. Thank you. All too often trying to debate with evangelicals and the like leads to just that. I have many stories of experiences with these guys but the most memorable was in college. I was a DJ and had my show just before the religious guys came on at 7 pm. They were sweet as pie. One week I had the chicken pox (as an adult, not good) and when they found out they were really compassionate, and said in a very genuine way that they’d pray for me. I didn’t have much sympathy from friends at that moment so it meant a lot.

But what a bunch of oddballs these guys were otherwise. I played a really eclectic mix; Industrial, sea shanties, Cocteau Twins, anything as long as it flowed and sparked good conversation. Well, when the guys were put in their time slot, they would sit down after my show and announce on the air: “You know what you just heard on the previous show? Well, dont’ believe anything you just heard. It’s all lies”.

I confronted them on it the first 2 times. I was like, what the heck? I didn’t play anything remotely offensive; can you sum up in a paragraph what my show’s actually about? Well, they couldn’t but obviously they were in their own little worlds. I was just amazed how two guys could be so sweet and such jerks at the same time.

LikeLike

amelie

October 17, 2012

I meant to add – I do think some religions make themselves useful. Earth religions like Wicca (that’s the one I used to follow) and Native Americans do have those pesky gods and goddesses; but they genuinely support science (including evolution, climate change etc) because they want to better understand and care for the planet. They also support self sufficiency and home growing, and they don’t prostelytize.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 18, 2012

I imagine your advertisers didn’t appreciate the comments of the guys who came on after your show. That’s too bad. Then again, “sweet” and “jerks” — that probably describes most of us.

You’re right about debate being fruitless. I keep forgetting that. I keep thinking I’m right, but so do they. The solution has to be based on something else.

LikeLike

greenroomgallery

October 17, 2012

Dear Charles, I have with interest read about your spiritual journey and in particular the catholic input. I grew up a rationalist became an atheist, had a spiritual encounter, spent years in the bible, became a christian, joined a biblegroup, joined a church, got involved, took on leadership, taught scripture in schools, became an evangelist, always researching, learning, questioning. Tasting tradition, religion, spiritual pride and the list goes on. After 20 years I had a wake up call 4 years ago. Was launched into outer space for lack of better explanation. Rediscovered God. Loads of going back into hebrew and greek. I am still a christian but feel as if I have come out of a club or a religious sect.

I don’t believe we have as so called free will to decide whatever. I think our opinions and beliefs are coloured by culture and circumstances. I believe now with all my heart that hell as a torterous eternal fire is total misinterpreted rubbish. If there is God then we are all loved and if He has decided to save mankind, then that He will do. In fact the Bible says that He will reconcile the entire universe to Himself. In the mean time I have lost the desperation to ‘win’ people for Christ and I seem to have lost the desire to judge others. I have hope and peace now more than ever and sometimes someone wants me to share which is fine, but otherwise it’s all about listening and encouraging. For a while I was angry with myself that I wasted my good years on religious life. But I am coming to terms with it. I have lived it. I know from my own experience what it means to be a pious, falsely humble, self righteous ‘born again’ christian. I didn’t see myself as religious at the time of course and it was only out of sincere concern for ‘lost souls’, that I had a burning desire to ‘save’ others. I didn’t see it at the time. I see it now. Hard lesson but for me the only way to learn. In the end we will no doubt find out where we were right and where we were wrong but for now we should just get along and allow each other to search and believe on our own terms. Thanks for sharing with us. 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 18, 2012

That’s a great story, Charlotte. It doesn’t sound as though you wasted time at all, but rather that you went through a genuine learning process, and that it continues. I worry a lot more about people who are sure they have all the answers. We all seem to have a piece of the truth — which is more reason to listen to each other. Thank you for a wonderful comment.

LikeLike

greenroomgallery

October 18, 2012

You are right of course. On bad, far-out-how-did-I-get-to half-a-century-so-quick-and-if-only-I-could-have-another-shot-at-it, kind of days I kick myself over time ‘wasted’ but on, far-out-I-have-come-along-way-since-my-silly-youth, kind of days I am thankful for all the lessons which has softened me and grounded me. Looking forward to what’s left to live and learn.

LikeLike

elvisinity

October 17, 2012

Reblogged this on Elvisinity.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 19, 2012

Thank you. I appreciate that you thought it worth re-posting.

LikeLike

jeanjames26

October 17, 2012

I grew up Catholic and I remember as a kid asking my mom what was going to happen to all the people who weren’t Catholic; like people who lived in Africa or on remote islands; were they all going to hell because they didn’t believe? Of course I got some answer that they would get a pass because they didn’t know any better, but I remember worrying about all the people who weren’t catholic and their fate. Now I think I’m more worried about all the people who are catholic. Maybe we shouldn’t be introduced to religion until adulthood, then we could make an educated decision, kind of like picking what college you want to go to…or not.

I enjoyed reading this series, it just proves the only one who can truly guide you in your beliefs is you!

So well done.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 19, 2012

I sometimes wonder how someone would react to the religious stories we swallowed whole as kids. Not that it all has to be about logic and reason, but some of that stuff was pretty bizarre.

Thanks for the comment, Jean. I know you left the Bronx when you were very young, but I wonder if you went to a Catholic school, and if so, where.

LikeLike

jeanjames26

October 20, 2012

I went to public school, (due to our financial situation), but I had to go to CCD at St. James the Apostle in Carmel. My parents were both Catholic school grads, my mom went to St Catherine’s Academy and my dad went to St. Nicholas of tolentine. I did make it back to the Bronx in my twenties for a couple of very non-religious years. Best times ever!!

LikeLike

winsomebella

October 17, 2012

Loved the open-hearted, brainy thoughts you have shared in this series. You said what I have thought many times and the last paragraph nailed it. Glad you did these at this time in our world process 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 19, 2012

Thank you, Bella. I just read your post about your recent trip to Montana. As always, the photography is incredible.

http://winsomebella.wordpress.com/2012/10/08/wandering-heart/

LikeLike

Marie M

October 17, 2012

Really enjoyed reading about your journey, bronxboy55. Thank you for, as always, expressing with such thoughtfulness and candor some of the ideas floating around in your head (and heart).

I rather think we *do* decide what to believe, “we” being those believers among us who haven’t been knocked off our horse in the manner of St. Paul. The heart must accept what the head chooses, of course; if religious belief never goes beyond the head into the heart, it remains a philosophy and is not a religion. On the other hand, I think a *desire* to believe can prepare the heart to receive what the head finds attractive, reasonable, or even just possible–that openness allows one to grow and develop and become more faith-filled. [I am aware that not everyone is interested in this journey.]

Perhaps you and your readers would be intrigued by a different approach to spirituality (not exactly religion). I recommend a DVD called “Journey of the Universe: The Epic Story of Cosmic, Earth, and Human Transformation” (www.JourneyoftheUniverse.org). I would love to hear folks’ responses/reactions, but am not suggesting beginning a discussion here. Any suggestions for how a discussion could take place?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 21, 2012

Thank you for recommending that film, Marie. It looks excellent, and I just ordered a copy. Maybe it will inspire a future post, and more discussion.

LikeLike

lostnchina

October 18, 2012

If all intolerance could be settled by inviting people with differing points of view to a glass of root beer, then all would be well with the world. Sigh.

Very well-written and timely too (Mormon Mitt). I had a friend who was as staunch an atheist as some religious people are about their faith. He condemned people for being religious. It’s not about the religion, it’s about the intolerance.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 21, 2012

An atheist condemning religion is just as destructive as the reverse. Absolute certainty is alienating enough — why use it to arouse hostility?

Also, I realize not everyone likes root beer. Lemonade could work, too.

Thanks, Susan.

LikeLike

TAE

October 18, 2012

Great post, Charles. I actually wrote one of my sillier poems about more or less this topic (if you care to read: http://theabrasiveembrace.wordpress.com/2012/10/06/deus-caritas-est/).

The older I get the more I “believe” that you can’t choose to believe or not to believe. I for one can’t, so I don’t delude myself into a state where I believe that I believe (I think this happens to some). Maybe some day I’ll write about about how I find it comforting that there’s no God in my book.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 21, 2012

I don’t think it’s silly at all, TAE. Your beliefs seem solid in the middle, with just enough softness around the edges to keep you flexible and open-minded. That’s what I’m striving for, too.

LikeLike

Anisha Gururaj

October 19, 2012

I loved this post and this series (like the rest of your writing!) It’s always been my belief that in regards to religion people should do what makes them happy. If that means going to church every Sunday, so be it. If that means saying a prayer before bed everyday, so be it. And if that means going through one’s life without considering these things, then ALSO so be it. Everyone just has to recognize that these things that make you happy don’t have to make everyone happy. Personally, I am a Hindu, but I wouldn’t call myself extremely religious. But even the most religious Hindus I know have never tried to convert others, and perhaps that’s what has preserved my ability to subscribe to an organized culture/religion without feeling the oppression of my thoughts. If I do what makes me happy, and the other person does too, maybe that’s the best situation.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 21, 2012

I agree, Anisha. Religious belief is just about the only area in which people try to change the internal life of others. If someone has found a philosophy or value system that allows them to function in the world without hurting anyone else, that’s good enough for me.

LikeLike

Margie

October 21, 2012

My sister is a born again Christian who has made it her mission to save me. She has not been successful in making me embrace her religion, however.

Several years ago her already tight budget couldn’t afford a turkey at Christmas. That didn’t bother her, because she was certain God would make sure she had food on her table. And God did, because that year I bought a turkey for her. God delivered, I was just the messenger.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 24, 2012

That was a nice thing you did — and especially so because you’re not an omnipotent being, but just a loving sister with limited time and resources of your own.

LikeLike

"HE WHO"

October 22, 2012

I read your four-parter at the behest of Michelle Gillies, who for some time has been trying to make a silk purse out of this sow’s ear. I’m the one she calls “He Who”. She knew I would appreciate your writing, especially on the current subject, and I did. When I went to University with the goal of changing careers, I was already in my late 30’s. I quickly found that some courses were interesting while others were not. I wound up majoring in subjects I liked – Philosophy and Psychology, which didn’t help me get a better job but did change my way of thinking. I had grown up with church (United) every Sunday (and Sunday school) and youth groups during the week. I had a fantastic minister and equally terrific Sunday school teachers. While not a zealot, I believed. Phil 101 changed that. While writing papers, I talked myself right into agnosticism. Even Pascal’s Wager couldn’t sway me. From there I took every Philosophy course that centered on religion and enjoyed them all. In Psych, I took courses like Transpersonal Pyschology and any others that offered small classes with T-Groups. When I graduated in 1989 I was sort of an athiest – I didn’t care either way, and I even started talking to J’s Witnesses at the door. I just liked to hear what they had to say. I have no problem with people and their religions. I’m happy they have a God to lean on. But, I agree with you that faith is a “private” matter, even though I enjoy listening. Politics, on the other hand, is on my barred list.

Looking forward to your next blog.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 24, 2012

It’s good to hear from you, HW. But did you talk yourself into agnosticism, or was it already there, waiting for you to catch up? (That’s how it was for me.) Pascal’s Wager makes sense only if you have the belief in the first place — its premise is that God exists, and he’s the God of the Christian Bible.

I used to love talking politics, but I find that most people are pretty much locked in to their opinions, and new information just can’t get in. I like to tell myself that I’m different, but I’m probably not.

Do you have your own blog? Please let me know.

LikeLike

Stephanie

October 24, 2012

I was waiting for this one and I missed it when you published this.

I’m always fascinated by peope’s religious beliefs. (Me, I don’t know what I am. Nothing-ish, except I think there’s probably some kind of God, who’s mostly good and non-interventionalist and some kind of afterlife which doesn’t involve hellfire.)

And while I like to discuss them because I am interested, I have no interest in arguing them, because I don’t think anyone ever changes their mind.

I agree with you that religion is a private thing and for years I’ve been of the opinion that life is hard, and anything that can give people comfort and support to get through it is good. As long as people aren’t hurting people with what they believe, I’m ok with it. And that includes the people who preach at the door, to be honest. They used to annoy me, but I read somewhere once that for them, not trying to save a person is equivalent to watching someone who can’t see or hear who is about to be hit by a train and doing nothing. So I give them leeway too.

I really do think that people try to do their best in this world, whatever they see that to be.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 25, 2012

I hope you’re right about the afterlife, Stephanie. And that’s what religious people don’t get about non-believers: everyone wants there to be an afterlife, because no one wishes to die and cease to exist forever. But there’s a difference between hoping something is true and being sure that it is.

As for the visiting preachers, I often see them as you do. But sometimes I feel as though they’re trying to save me from a train that isn’t even there, and that can get tiring.

LikeLike

Stephanie

October 26, 2012

I think I fall somewhere between the hoping and the being sure. I’m certainly not sure of anything, and when it comes to this stuff, there’s only one way to find out and I’m not ready for that. But it just kind of feels to me that there would be. In no way do I feel any need to win anyone over from either side of the fence though.

Every now and then, I have a vague worry that one of the groups is just 100% right, that it’ll be one of the hellfire groups, and that the rest of us are going to seriously suffer. Wanting that not to be the case, I guess that’s where I think hope comes in for me.

LikeLike

icedteawithlemon

October 25, 2012

I have loved this entire series, Charles, but this last installment particularly resonates with me. “What we really should be doing is less talking and more listening, building bridges instead of blowing them up, practicing the tolerance every religion professes to cherish.” Yes, yes, yes. Perhaps I have a simplistic view, too, (that’s certainly what all my Bible-belt neighbors think when I suggest tolerance of others’ religious beliefs), but I whole-heartedly agree with your ideas of keeping my relationship with God a private matter and “leaving each other alone.” Religion is such a difficult subject to write about, but you have done so with tremendous eloquence. Peace be with you.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 25, 2012

It doesn’t surprise me that you endorse tolerance. How else could you have had such a successful career as an educator and school administrator? Thank you, as always, for your kind words, Karen.

LikeLike

aunaqui

October 25, 2012

Loved this comment! “Leaving each other alone” in matters of religion is definitely the most respectful, rational, humane thing people can do.

Aun Aqui

LikeLike

aunaqui

October 25, 2012

A thousand thanks for this post, Bronxboy. It really touched me. Everything that you said is so relative to what I’m going through right now. I had started a blog post and set it aside about a month ago on a similar topic: religion. I was going to title it “I will not subscribe.” I sort of lost my guts and forgot what I wanted to say.

I grew up in an elite, conservative Christian denomination and claimed the tenets of the faith as my own until recently.. really, until earlier this year. My husband and I just abruptly stopped going to church.. didn’t give a reason or explain “why” to anyone because we weren’t sure as to whether it was just a “phase” and we needed a break or it was going to be a permanent “removal” of ourselves. As time has gone on, my entire outlook and mindset has changed: I just don’t want to be that person anymore, that person who is completely convinced that out of ALL of the millions of peoples and views and beliefs out there, I have found “the” right one and I need to convince everyone around me of it. I don’t want to control other peoples lives, actions and standards.. it’s not my place (and I used to think it was). I no longer respect people who WANT to control other peoples lives in ways that are unreasonable and religion-based.

I have honestly found myself at both extremes: the most earnest promoter of Christianity (my whole life), and then a few months ago, the most disgusted basher OF it. I’ve found a medium now, where I can appreciate and respect all religions and all beliefs.. even the one I had a bad experience with. It’s just hard, moving on. It was such a part of my childhood and my personal make-up that I’m sort of at a loss. It’s hard, disappointing your family (who still doesn’t know you’ve “given up the faith”) and losing touch with half of your friends from Facebook because all of them know you as the saintly girl who used to preach sermons on youth Sabbaths.

It’s difficult.. so I appreciated your post and your words of encouragement. I agree with everything that you said, and I find your blog to be more interesting, intelligent and inspiring in its few hundreds/thousands of words than any book I’ve read in the past year.

Take care, friend! I really appreciate you.

Aun Aqui

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 26, 2012

I think the process you’re going through is similar in some ways to the one you recently experienced after your visit with the oral surgeon. There’s a lot of pain at first and it feels as though you’re going to bleed to death, and that nothing will ever be normal again. But you inch back, a little at a time, and one day you wake up and realize you feel good. The people who are solid in their faith will have no trouble being with you, and the more sure you feel about where you are, the more comfortable you’ll be with those who have different beliefs. Your true friends — like the one who took a day off from work to sit with you while you recovered — will be there. I’m sure your family will, too. Still it is hard to lose that shared identity, and “moving on” may make you appear as though you’re confused, even though you’re thinking more clearly than ever. Be patient with yourself. You’ll figure it out.

http://aunaqui.wordpress.com/2012/10/24/losing-wisdom/

LikeLike

aunaqui

October 26, 2012

Thank you for the words of advice, friend! I’ve taken them to heart. You’re right — I do feel confused, muddled, and unsure.. but it’s a journey. It’s comforting to know that I’m in good company! 🙂

Aun Aqui

LikeLike

mostlikelytomarry

October 29, 2012

I truly loved this post. It really resonated with me at this point in my life. I especially loved the sentence, “Nobody knows what they’re talking about, and that should tie us together, not tear us apart.” Amen, my friend!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 30, 2012

You know, I’d been planning to write these posts for a long time, but dreading them, because I was expecting a flood of closed-minded disagreement and even some hostility. None of that happened. Instead, even the most devout believers — at both ends of the spectrum and everywhere in between — have been sincere and respectful in their responses. Maybe there’s hope after all.

LikeLike

mostlikelytomarry

November 5, 2012

I hope so. It is inspiring that you had such a good response to these. Thank you for being so brave and putting your thoughts out there.

LikeLike

ArborFam

November 5, 2012

Charles,

These are very thoughtful reflections on belief. Thanks for sharing. Thanks also for opening this post for comments.

When I think of belief, I think of it in the same vein as intelligence and physical ability. In all these aspects of life, I believe our current situation in life is a combination of nature and nurture.

Take physical ability, for instance. Some people are blessed with bodies that are more suited for athletic competition or specific types of hard work than others. Some people’s hands are a little bigger or their arms a little longer or their muscles respond better to stress or their neurological systems are a little more effective than the rest of ours. I think if you look at professional athletes, some combination of these advantages are present in their natural make-up.

That being said, no professional athlete hasn’t spent hours upon hours honing the natural benefits that she has. Anyone who reaches the highest levels of attainment has spent uncountable time and energy developing their skills and abilities. They have learned the best tactics in their field of activity. They have found ways to motivate themselves, even when things get difficult. They have mastered the skill of avoiding distractions and determents to get to their goal.

All of this holds true in the area of intellectual activity as well. I do not believe we could all have developed into an Einstein or Hawking or Edison. These men (and many other women and men) have a special natural ability to process information and think critically in ways that the rest of us can’t—no matter how much effort we apply.

On the other hand, Einstein, Hawking, Edison and anyone else who effectively uses their intelligence to solve great problems doesn’t merely rely on the benefits they naturally inherited. They all work tirelessly. Wasn’t it Edison who said genius was 99% perspiration and only 1% inspiration?

I think the same is true of belief. We all have a measure of belief-ability, just as we have a natural potential for intelligence and physical prowess. What we do with our natural belief-ability then remains up to us. We can work tirelessly and exercise consistently to build our belief. We can strive to learn all we can about belief and master the skill of overcoming all distractions and determents. Or we can do the equivalent of sitting on the couch and playing video games—we can squander whatever belief-ability we have, just as so many among us squander their intelligence or their physical abilities.

This is my current, best understanding of how belief works. Lots of years of thinking about life and reading and observing others have brought me to this perspective. But I’m only 40 years old, and I’m sure I still have lots to learn.

Every day, I try to do my best to use the natural benefits I have—intellectually, physically, emotionally, relationally and in the area of belief. And yet, I know there is so much potential waiting in me that I haven’t tapped. And I see so many around me who leave natural benefits untapped and lead lives that aren’t as full or as deep as they could be and it makes me sad.

I’m glad you struggle with these deep things and share your thoughts and invite ours. This type of dialogue is so important for all of us. Thank you.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

November 7, 2012

And thank you, Kevin, for this most thoughtful response. But I still think belief is in its own category. How our beliefs are formed — and how they change over time — is connected to things happening in some part of our brain that’s separate from the part that makes conscious choices. At least that’s how it feels to me. What I believe then affects what I read, how I filter the opinions of others, and other belief-related behaviors. But it doesn’t seem to be something I directly control. It’s more like an involuntary response, like hunger. I don’t decide to feel hungry, but I do decide whether or not to eat, what to eat, and when. (I already sense the weakness of that analogy, but it’s the best I can do right now. I imagine this conversation will continue for some time, anyway. Thanks again.)

LikeLike

Shama Sheikh

November 13, 2012

I have enjoyed reading your serial account of an important journey of evolvement Charles! I am as always, blown away at the similarities in our so called polar societies and belief systems…from the dogmatic to the emphasis on virtues of tolerance…truth and understanding…

A favorite scholar of mine has put this rather well I think….Dr Khalid Zaheer says…The real battle of good and evil is fought inside the human soul. It is won or lost there. The material world witnesses physical expression of it. Hatred doesn’t begin when people start abusing, attacking and killing each other. It starts when they decide not to listen to the other view. To be critical isn’t a problem; to not be receptive is a serious one. One needs to be open to other ideas even while being critical of them…

The prayer and personal effort for such a world continues….

LikeLike

bronxboy55

November 15, 2012

I think it would help if we all accepted that to be different isn’t a problem. But I’m encouraged by your comment about the similarities, too. That means that underneath all of the superficial details, we do have a lot in common — so there’s hope.

LikeLike

J-at-X

November 15, 2012

Reblogged this on La Biblia Atea and commented:

Mormones y sus particularidades. La felicidad ante todo. Por eso: ¿dejar en paz a las personas no es parte de una vida feliz?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

November 29, 2012

Muchas gracias, J-at-X.

LikeLike

113yearslater

February 7, 2013

Feel silly finding this so much later — my apologies for poking a sleeping post, but I’ve just been thinking about some of this stuff lately. I’m atheist FWIW; I was born with a little scientist’s brain, so at a fairly young age I figured well, if there’s no proof of it, then don’t bother believing until you know more. I was remarkably angst-free about this and still am although the church’s general behavior has been pretty horrific for a while now and it deserves most of the bile thrown at it as a result.

But I just started learning about the differences between the cold, mean catholicism that I grew up with and the nicer, more festival-oriented catholicism that my mom grew up with. Both her parents were immigrants, and she grew up in South Philly, so there were lots of those practically-pagan Italian saint’s day parades and parades of the Blessed Mother being cheered at while being carried through the streets, and that sort of thing.

I only recently learned about the really extreme lengths that the American catholic church went to to stamp all of that out and force the far rigid, uglier (and honestly, more Irish catholic) version of itself onto us. They really went way out of their way to stamp out what they actually called uneducated, ignorant, pagan catholicism, but what they replaced it with was just ugly, hateful, and rigid. I learned what wop and dago meant in catholic school and church, and all I remember is a bunch of mean-ass adults who never once smiled and none of whom had last names like mine. My mom, who is still catholic, remembers the statue of the Blessed Mother being carried through the street with money pinned to her, and people singing and dancing.