One Christmas Eve in the early 1960s, my mother told me to go to bed, because Santa Claus wouldn’t come to homes where the children were still awake. This made sense to me. What made no sense, although I didn’t give it any thought at the time, was that the Christmas tree was set up in my bedroom. I guess it’s more accurate to say that my bed was in the living room. This must have had something to do with the fact that there were now five kids in the family, and there weren’t enough places for beds. A light sleeper even then, I woke up at the slightest sound, and when I opened my eyes that night I saw my father putting wrapped gifts under the tree.

One Christmas Eve in the early 1960s, my mother told me to go to bed, because Santa Claus wouldn’t come to homes where the children were still awake. This made sense to me. What made no sense, although I didn’t give it any thought at the time, was that the Christmas tree was set up in my bedroom. I guess it’s more accurate to say that my bed was in the living room. This must have had something to do with the fact that there were now five kids in the family, and there weren’t enough places for beds. A light sleeper even then, I woke up at the slightest sound, and when I opened my eyes that night I saw my father putting wrapped gifts under the tree.

Up to that point, I’d been holding fast to the childhood illusion that Santa was a supernatural being who represented goodness and generosity, an otherworldly visitor who came once a year to remind us of what was possible. But now I had to face hard facts, and my mind immediately came to the only logical conclusion I could find: my father was Santa Claus! Just as Superman and Batman had secret identities, Santa had one, too — a person he pretended to be all year long. I’d wondered about that possibility before, but I expected his secret identity to be a retired baseball player, or maybe Captain Kangaroo. The idea that he might be a spice salesman from the Bronx had never entered my mind. On the other hand, this did explain the so-called bowling league on Tuesday nights: he was sneaking off to make toys! But why wasn’t my father wearing the Santa costume now? I didn’t know, but I was sure he had his reasons.

The following year, on Christmas Day, my father and I went to visit his cousin, a man with eyes like those of a barracuda, and lips that never approached a smile. He was, I was sure, a vampire, and I was terrified of him. Again, this was back in the 1960s, when vampires were still people you didn’t want to hang around with. But he was interesting, too. He had the first speaker phone I’d ever seen; it was a black box that sat on his desk, and he demonstrated it for my father and me. He dialed a number, then connected the phone to the box somehow, and we waited. Sure enough, from across the room, we could hear a voice that seemed to come from nowhere. My father looked at me with pride, expecting me to be amazed and impressed. I was certain his cousin had murdered someone, drained his blood, and injected the person’s soul into that contraption on his desk.

In 1965, my grandmother got a pain in her leg, went to the doctor, and found out she had a brain tumor. I was nine, and had no real conception of what that meant. I just knew she had to go into the hospital, and was there for quite a while. When she came home, I interpreted that as a sign that she was getting better. My grandmother lived upstairs, on the third floor, and I went to see her every day. I noticed that she almost never got out of bed, and that her hair was suddenly gone. And she looked tiny, even to me, and I was pretty small myself. For Christmas, I got her a brush and comb set. They were light purple and came in a see-through plastic box with a ribbon around it and a bow. I thought it was a good gift for when her hair grew back. On New Year’s Day, 1966, New York had a new mayor and my grandmother began her last two months of life. She died in early March. The brush and comb were still in the plastic box next to her bed.

Several years later, I’d pretty much decided that my father’s cousin wasn’t a vampire, but just one of those relatives who, for some inexplicable reason, seemed creepier than he probably was. I’d also assured myself that my father wasn’t Santa Claus, or even Captain Kangaroo. But gifts did arrive mysteriously every Christmas Eve, and wherever they were coming from, I was sure that a Frosty the Snowman Sno-Cone Machine would be waiting for me under the tree. It wasn’t. Sensing my shock and disappointment, my uncle tried to ease the pain by explaining that I simply wasn’t old enough for a Sno Cone Machine. I couldn’t accept that. This was crushed ice and cherry syrup, for crying out loud. Besides, his son was two years younger than me, and he’d gotten a chemistry set that included enough acid to melt half of Manhattan. I’d had a vision of people lined up around the block, waiting to plunk down a shiny new dime for a paper cone full of my Famous Old World Style Flavored Sno, with “Snow” spelled without the W, just like they did in the olden days. As the grown-ups gathered the torn and crumpled wrapping paper from the floor, that vision evaporated into thin air. My ten-year-old cousin, meanwhile, got right to work dissolving the lower branches of our aluminum Christmas tree.

On December 21, 1968, three astronauts were launched into space aboard a Saturn V rocket. Their mission was to leave the planet’s orbit — the first humans to do so — and circle the Moon. On Christmas Eve, they broadcast live from their command module, reading from the Book of Genesis and wishing everyone on Earth a Merry Christmas. My family was in the kitchen, eating and laughing and speaking in loud voices, yelling the way they tended to do even when there was no discernible reason for it. I sat on the living room floor, alone, and listened to the astronauts. I didn’t believe the Bible account then, any more than I do now, but it was nevertheless the most wonderful Christmas Eve I’ve ever had. The year 1968 had been, in many ways, a difficult one, filled with anger and hate. For those few minutes that night, it seemed possible that we might all get past those destructive behaviors and realize that we shared this small planet, and that we’d be better off if we could just treat each other with tolerance and respect. The promise of Christmas, the returning light marked by the winter solstice, and the coming new year seemed, at least to me, to be brimming with hope.

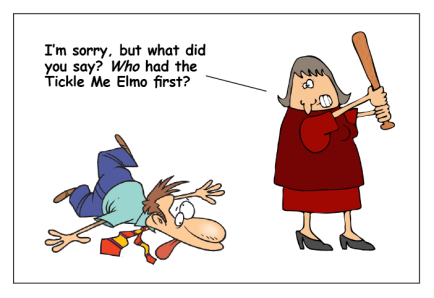

Almost three decades later I walked into a toy store, looking for a gift for my eleven-year-old daughter. Wandering up and down the aisles, I picked up and put down dozens of things that seemed too violent, too childish, or just too pointless. One of the items I rejected immediately was a red plush toy that, when squeezed, would laugh like an intoxicated chipmunk. It was called Tickle Me Elmo, and when I looked at its thirty-dollar price tag, I shook my head and threw it back onto the shelf. Nobody, I thought to myself, is ever going to pay that much money for such a stupid toy. Weeks later, just before Christmas, people all over North America were punching and stabbing each other to get their hands on a Tickle Me Elmo. I remember wishing I were sleeping in our living room again, next to the tree, discovering against all odds that Santa Claus was really a mild-mannered spice salesman from the Bronx. My grandmother would be upstairs, cleaning up after our Christmas Eve feast and preparing the next day’s dinner. Those were days when people got excited about a voice coming from a box sitting on a desk. When kids dreamed of something as simple as a cupful of flavored ice. When the world watched and listened as one, and saw pictures for the first time of the home they all shared. They seem like ghosts now, every one of them. And yet, there’s something about them that’s still alive, and still possible. At least, I hope there is.

Almost three decades later I walked into a toy store, looking for a gift for my eleven-year-old daughter. Wandering up and down the aisles, I picked up and put down dozens of things that seemed too violent, too childish, or just too pointless. One of the items I rejected immediately was a red plush toy that, when squeezed, would laugh like an intoxicated chipmunk. It was called Tickle Me Elmo, and when I looked at its thirty-dollar price tag, I shook my head and threw it back onto the shelf. Nobody, I thought to myself, is ever going to pay that much money for such a stupid toy. Weeks later, just before Christmas, people all over North America were punching and stabbing each other to get their hands on a Tickle Me Elmo. I remember wishing I were sleeping in our living room again, next to the tree, discovering against all odds that Santa Claus was really a mild-mannered spice salesman from the Bronx. My grandmother would be upstairs, cleaning up after our Christmas Eve feast and preparing the next day’s dinner. Those were days when people got excited about a voice coming from a box sitting on a desk. When kids dreamed of something as simple as a cupful of flavored ice. When the world watched and listened as one, and saw pictures for the first time of the home they all shared. They seem like ghosts now, every one of them. And yet, there’s something about them that’s still alive, and still possible. At least, I hope there is.

Merry Christmas.

Almudena

December 23, 2011

Brilliant!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 25, 2011

Thank you, Almudena, both for taking the time to read this post and for commenting. I know it’s been a busy and stressful time for you. I hope the new year brings better things.

LikeLike

Jac

December 23, 2011

So what are you saying – that you had no bedroom because of me? 😉

I actually thought this blog was going to be about A Christmas Carol. “I don’t know anything…”

I wish Christmas could be the way it used to be, too. Remember taking a walk up and down the block in Nanuet, and being amazed at how quiet it was? It truly felt like “Silent night, Holy night”….

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 25, 2011

Maybe everything seemed better back then, just because we could still allow ourselves to believe it would all go on forever.

Merry Christmas, my one and only sister.

LikeLike

O. Leonard

December 23, 2011

Wow! That was great. Flashed me back. I was also alone in the living room listening to transmission from Apollo on that Christmas Eve. I bet my mother $300 that we would land on the moon by the end of the decade and she was considerably worried about losing that bet right about then.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 25, 2011

I don’t think you’re supposed to gamble on Christmas Eve, O.

So did she pay up?

LikeLike

worrywarts-guide-to-weight-sex-and-marriage

December 23, 2011

I’m so frustrated right now with my inability to put into words how meaningful this post is to me. Almudena did a pretty good job. Merry Christmas.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 25, 2011

Merry Christmas to you, too, WW. Thank you for your consistent encouragement. And I appreciate the way you write about life on your blog. There’s so much there, a reader could wander in and never be seen again.

http://worrywarts-guide-to-weight-sex-and-marriage.com

LikeLike

heidit

December 23, 2011

Wonderful post, Charles. The good news is that although Christmas for you might not be like those Christmases in the 60s, there are many children I know who view Christmas with that same wonder. One of my friends–now grown up–once went to visit Santa at the local mall only to discover that Santa was her uncle. And that’s what she believed until he told her he was just helping Santa out for a few days. Then she believed her uncle had a direct line to the jolly man. Now, her nieces and nephews hold that same belief about their great uncle.

In some ways, I don’t think it’s the kids that force the meaning out of Christmas, it’s the adults. Oh sure, some kids act spoiled, as I’m sure I did growing up. But rational adults realize that most of the presents their children receive will be long forgotten before January is out, and rather than stabbing people to get a doll that laughs, they focus on a couple of meaningful gifts.

For most children, though, the magic of Christmas is still there, regardless of whether they get a Tickle Me Elmo, a Playstation or an iPad. Because what most of them remember isn’t the presents they got, but the anticipation of waiting for Santa Claus and the sense that something magical was happening.

Merry Christmas, Charles. I hope 2012 is an amazing year for you and your family.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 25, 2011

A good friend of mine said the very same thing about anticipation just the other day. Maybe the reality too often turns into a big letdown, and we should learn how to enjoy the building excitement — for its own sake.

Thank you, Heidi. Merry Christmas, and I hope the new year brings you all of the good things you deserve.

LikeLike

VeggieSandwichGeneration

December 23, 2011

I like hope – where would we be without it?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 25, 2011

I guess we’d be hopeless. Fortunately, no matter how bad things get, most people never quite reach that point. It may seem hopeless at times, but something keeps us moving forward.

LikeLike

souldipper

December 23, 2011

I remember exactly where I was and who I was with when I listened to these words. I, too, felt a strength, a promise, a drop of reassurance that I didn’t even realize I needed.

I remember being struck by the fact that these men would have a Bible with them. Now that I’m older, I realize that no matter the belief system, anyone experiencing such a feat would be profoundly moved by whatever Divine path was ‘home’.

Merry Christmas to all your loved ones and you, Charles.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 26, 2011

I didn’t think about it at the time, but I do now find it curious that they read from the Bible. I’d love to know what kind of debates they had before deciding on what to read. The images they sent back of the Earth were the first we’d ever seen of the planet as a whole, and a lot of people were struck by the fact that all of the political boundaries we have in our heads are completely artificial. From space, it’s just one planet. As you suggest, the same could be said for belief systems. I don’t think the lesson stuck, though. Maybe someday?

I hope you had a wonderful Christmas, Amy.

LikeLike

Lenore Diane

December 23, 2011

For what it is worth, Charles, Rob and I work very hard to keep our kids’ natural wonder thriving. We believe in playing outside, lighting campfires, reading books, playing board games as a family and watching the stars. The spirit of Christmas is alive in this house, and I hope our boys carry this tradition when they get older.

Thank you for posting the video.

Merry Christmas to you and yours.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 26, 2011

I have a feeling your boys will continue doing those things for the rest of their lives, and will hand them on to your grandchildren.

Merry Christmas to you, too, Lenore. And thank you for all of the wonderful posts you’ve written this year. I look forward to more.

LikeLike

Linda Sand

December 23, 2011

Nya, Nya. I got the sno-cone machine. 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 26, 2011

You’re just trying to take your mind off the mirror problems.

http://sandcastle.sandsys.org/2011/12/mirror-mirror/

LikeLike

charlywalker

December 23, 2011

What???? Santa isn’t real???…….

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 26, 2011

I never said that.

LikeLike

JSD

December 23, 2011

All the images you recalled of the Christmas past are still alive. They’re alive here in your writing, in your heart, and in the hearts of all of us who lived through the seasons when life was less commercial, more simple and full of wonderment. They’ll never be ghosts as long as we keep them alive. Merry Christmas!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 26, 2011

Merry Christmas to you, JSD. And thank you for those hopeful words.

LikeLike

Betty Londergan

December 23, 2011

Thank you for all your amazing, wonderful, hilarious and heartfelt posts throughout the year, Charles, but especially for this one. As I was scrolling down and reading I thought: gee, i wish i could see that video of the astronauts reading Genesis — and then, voila! there it was. As always, you just seem to know what we need to see & hear … Happy Christmas!!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 26, 2011

Betty, you’re not only one of my favorite writers, but one of my favorite people, too. I know you have an exciting year coming up, and I’m just one of many people who are watching, waiting, and cheering you on. The world will continue to benefit from what you do; I’m sure of that.

LikeLike

Carol Deminski

December 23, 2011

So apparently Santa Claus has brought all the Sno-Cone making equipment here to New Orleans where I am officially on vacation for the holidays. There are Sno-Cones (in the old timey way, without the “W”) everywhere. (I do mean everywhere) I haven’t had one, but for the purposes of this comment, let’s imagine I got one for you. The cherry kind.. Happy Holidays.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 27, 2011

Can you make it grape instead? I mean assuming you haven’t already had the cherry one.

Thanks for the comment, Carol. And happy holidays to you, too.

LikeLike

Margaret Reyes Dempsey

December 23, 2011

What a good read. Hope you have a joyful holiday season.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 27, 2011

You too, Margaret. Let’s catch up soon.

LikeLike

Coyotemoonwatch

December 23, 2011

Boy oh boy. Your blogs are like getting the monthly issue of The Sun Magazine: I drop everything to read it. It always brings some emotional response along with it: smiles, laughter, sadness, tears, hopes… This transported me to so many of my Christmases of years past, many of which were not happy, though each one always carried the hope that “this year would be different.”

And it finally is different. It’s not filled with wonder and expectation of what gift might be received or fear of seeing disappointment in a child’s eyes, but just filled with love and friendship and sharing. This year, as last year, I’m outside a small town in Costa Rica, and though you see some hint of Christmas, with tiny plastic decorated Christmas trees on front porches (not IN the house) and a few decorations, for all the TIcos I know, there is no Santa Claus secretly placing presents under trees for the good little boys and girls; there are no presents exchanged at all. And I like that.

What there is, though, are wonderful family parties — fiestas — where they play loud music late into the night on Christmas Eve, with much dancing and singing and eating. We join them and celebrate a wonderful togetherness and sharing. If people go to church, they go on Christmas Eve; for many, Christmas Day is no different, and many people will actually choose to go to work doing construction or any other normal-day activity. But usually, during the day on Christmas Eve Day and on Christmas Day itself, there are festivities in the local towns, with cabalgatas (horse parades) and food and, again, loud music, and people sauntering slowly down the streets. To prepare for these two days, mounds of tamales are being cooked, pigs are being butchered, yucca and other starchy roots are being prepared. Larger-than-usual pots of beans are being cooked. No commercialism. Nobody fighting over some Tickle Me Elmo.

What was wonderful about your blog is it did remind me of that hopeful magic I had, both as a child and as a parent; but it also brought with it the sad idea of why, why — when I hear everybody talk about their magical Christmases — why, sadly, in spite of how much I tried, the magic anticipation of Christmas never quite happened in my life? It always dissipated quickly on Christmas morning, being filled instead with disappointment, hurt, anger, and fighting. What happened in my family to always have Christmas be such a horrible time of the year? I still don’t know. But admittedly your blog has brought tears of sadness to my eyes for all those Christmases past that, for whatever reason, never were magical for me and always left me so sad and hurt.

But 62 years later I honestly look forward to and enjoy Christmas here in Costa Rica. There’s no false hope or anticipation attached to it; there’s no commercialism. It’s just a day of friendship, love and sharing.

Thanks again for your beautiful thoughts. Wonderful.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 28, 2011

I think your comment was better than my post. Do you have a blog where you write stuff like this description of Christmas in Costa Rica? I’d love to read more, and I’m sure there are others who would, too. “There’s no false hope or anticipation attached to it; there’s no commercialism. It’s just a day of friendship, love and sharing.” Perfect. Thank you.

LikeLike

Coyotemoonwatch

December 28, 2011

Well, thank you. To be honest (which sometimes is my downfall), I feared my reply to your post carried a bit too much of my sadness and disappointment in those Christmases of the past, especially after reading everyone else’s upbeat and cheery replies. I thought, boy, am I ever a fly in the ointment? And then the next cliche entering my brain would have a tune attached to it: “When will they ever learn? with the finger pointed at myself and no one else but all the while hoping that I conveyed the old, deep emotions your post stirred in me, feeling like I was watching a replay of a continuing movie of a little girl holding that hopeful magical excitement of a coming Christmas only to have it disintegrate into bad memories. The reality is the memory of that hopeful magical excitement never goes away, and it’s your post that stirred the embers covered with the building ash of by-gone years. Your kudos are like a little Christmas present for me!!

And, yes, I did start blogging (which is how I discovered your blog on wordpress when you got Freshly Pressed): Vasilado.wordpress.com . I wrote a few blogs, and then got a little lax in writing, one, because I got sidetracked writing (finally) my travel stories of sailing in the South Pacific for seven years back in the ’70s; and, two, because time seems to disappear just as quickly living a less harried life in Costa Rica as it did when I worked 24/7 in the States transcribing court trials all day long. Oh, and third, rainy season is over, and I find myself pulled outside more, taking long walks to visit friends, cutting the encroaching jungle back from my bananas and coffee, doing some mosaic tile work on a retaining wall……… But maybe with your nudging, I’ll make myself another great cup of Costa Rican coffee and allow my fingers to fly.

(Oh, and there’s no way my reply could beat your excellent writing — I just love everything you write.)

LikeLike

rangewriter

December 23, 2011

You came from a rich tapestry of family members. You honor them in the stories you weave. Wishing you all the best during this season and the year to come. I always look forward to your posts.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 28, 2011

Thank you, Linda. I feel the same way about your posts. Happy New Year.

LikeLike

Sandra Parsons

December 23, 2011

“back in the 1960s, when vampires were still people you didn’t want to hang around with” – keen observation that!

I have to admit, I hardly remember the 1960s, mainly because I was born in 73. Growing up in East Germany, what I do remember though is that Christmas was never as commercialised as it is today. It’s hard to believe, but we actually got much-needed clothes for Christmas, and they didn’t have any Hello Kittie or Bob The Builder characters on them (or whatever their contemporary equivalents would have been).

I guess in the end it’s not the memories of the ‘good old times’ but rather how we decide to live our lives today that makes us happy or unhappy with ourselves. Hopefully happy of course.

Happy Christmas to you and your loved ones, Charles.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 28, 2011

I know your blog is about your current life in the UK, but I wonder if you’ve written much about growing up in East Germany. I think a lot of people would be interested in that, because it’s still such a mystery to most of us in the West.

Thank you for reading, Sandra, and for the comment. Happy New Year!

http://islandmonkeys.wordpress.com/

LikeLike

Sandra Parsons

December 28, 2011

Ha, there’s an idea. Why didn’t I think of that?

I guess it’s just so long ago and in my everyday life I usually don’t feel that this child’s life behind the Iron Curtain has all that much relevance for my current life. Although I suppose we all are shaped by our childhood experiences in some way or other… Anyway, I’ll let you know when I make up my mind.

Thanks for linking to my blog and Happy New Year to you too.

LikeLike

Anonymous

December 23, 2011

Nice blog Charlie. Recalling Christmas’ when you were little. Good description of your father’s uncle if it is the one I am thinking of. Made me laugh.

Merry Christmas! Love to the family.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 28, 2011

It was my father’s cousin, although I avoided using his name. I’m sure you’re thinking of the same person.

LikeLike

Nel

December 23, 2011

My favorite parts of Christmas were the midnight dinner we ate together as a family (a tradition we call Noche Buena) and my cousins coming over to our house on Christmas morning for candy/gifts (a lot like trick-or-treat in Halloween). I later realized that I enjoyed them because they were rare; it’s not every day that I get to thoroughly enjoy meals with family or have lots of giddy kids around the house.

Merry Christmas to you, Charles.

P.S. I’m anxiously waiting for your book (Who Knew?) to be delivered.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 28, 2011

Your family’s Christmas tradition sounds exactly like what I wish for, Nel — family meals, happy kids, and small gifts that top off the event, but don’t dominate it or give it meaning. I hope it was a wonderful night.

Thank you for buying the book. That means a lot to me.

LikeLike

John

December 23, 2011

Your writing is consistently wonderful and heartfelt. Merry Christmas!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 28, 2011

Thank you, John. That’s nice of you to say. Merry Christmas to you, too.

LikeLike

MJ, Nonstepmom

December 23, 2011

Your sno cone machine is my easy bake oven. But what I did get was a danish grandmother who taught me everything from her kitchen – far more than I would have gotten from brownies baked over a lightbulb. I’ve never seen the Genesis video clip, thanks.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 29, 2011

I have a feeling that Sno Cone Machine would have been disappointing, MJ, no doubt just as much as that Easy Bake Oven would have been. But I think it takes a grown-up mind to appreciate the priceless lessons learned from a grandmother and her kitchen. Thanks for the comment.

LikeLike

patricemj

December 23, 2011

Merry Christmas BronxBoy! This post made me feel like an immigrant in my own country, moving into a new world I do not understand. That old world has vanished.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 30, 2011

At least it hasn’t disappeared completely, Patrice. As long as we remember and find ways to share it, that vanishing world will hang around a little longer.

LikeLike

magsx2

December 24, 2011

Hi,

One of my Uncles used to be a Santa Helper as well, many moons ago, and I used to think he was very special indeed. 🙂

A very Merry Christmas to you and your Family, and I’m certainly looking forward to reading your posts in 2012.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 30, 2011

The same to you, Mags. Thank you for another year of great stories, jokes, and videos. Your blog is one of my favorites.

LikeLike

Joseph M Kurtenbach

December 24, 2011

Great post, Charles. I used to love watching all the TV coverage I could of those Apollo missions. I was born in ’60 so I fancied myself a true child of the space age — and figured I’d better keep current with all the space age stuff going on out there. My love of all things science has never waned. Beyond that, or should I say, much closer to home than that . . . I’ve been doing my own bloginiscing the last couple of days; there’s something profound in those memories of youth. Nothing else in my life can be so sad, uplifting, confusing, and funny all at the same time. There must be a lesson in there somewhere that I can apply to my current life. Maybe someday I’ll figure out what it is.

*Cue Bob Hope theme song.* Thanks, Charles.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 30, 2011

I watched all of the Moon landings, too, even long after most people had gotten bored with them. Would you have ever thought that forty years later, we’d have such unclear goals for space exploration?

Thanks for the comment, Joseph. Happy New Year.

LikeLike

juegosdeazahar

December 24, 2011

My sisters and I (we slept in the same room) used to try to stay awake to see Santa Claus through the keyhole, but we usually ended up sleeping before 1 am.

However, when I was 6 or 7, it was my turn at the door and I saw my father tiptoeing down the hall with the Garfield alarm clock my sister wanted for Christmas, and my mother was following him with a bunch of other things! I still remember getting stuck for 5 minutes until I told my sisters that I hadn´t seen anything yet.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 30, 2011

Six or seven was pretty young. I wonder how you interpreted what you saw that night. Were you confused by it?

LikeLike

slavesincorporated

December 24, 2011

Hi Charles, I couldn’t help doing a Christmas post myself

a new study says gifts are more for the giver than the receivers, specially in terms of how expensive they are

I plan on quoting this research very often

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 30, 2011

If Christmas has turned into a stressful time, I think we pretty much did it to ourselves. And it may have a lot to do with the results of that study.

LikeLike

Amiable Amiable

December 24, 2011

I’m trying to think of a profound comment after watching the video, but all I can think of is “Spice Claus.” Wishing you and your family a wonderful Christmas!

AA

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 30, 2011

I’m looking forward to another year of reading your blog, following your adventures, and enjoying your friendship. Thank you for everything, AA.

LikeLike

Westchester Square

December 24, 2011

It’s Christmas eve morning, my house is still quiet, and reading your blog is like giving a gift to myself. Thanks for giving me a few minutes to reflect on my childhood Christmases, including all the people who used to be part of this celebration, and all of the people who fill my heart and my house today.

Merry Christmas, Charlie.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 30, 2011

It’s a time of mixed emotions, WS. I know exactly what you’re talking about. I hope you had a wonderful Christmas, and I wish you a new year filled with happiness. It’s so great to be back in touch with you.

LikeLike

Samantha

December 24, 2011

Let’s enjoy the meaningful moments of this season–

Merry Christmas!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 30, 2011

The same to you, Samantha, and Happy New Year!

LikeLike

Sarah

December 24, 2011

This is beautiful, Charles. I was most struck by the brush and comb set for your grandmother. There was thoughtfulness and hope in that purchase, which I find so sweet and poignant, I’m tearing up even now. Thank you for sharing this and all your wonderful posts this year. Looking forward to many more in 2012.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 30, 2011

Thank you, Sarah, for all of your kind words and encouragement. I’m grateful for our renewed friendship this year, and I hope 2012 will be a healthy one for all of us.

LikeLike

Diane Henders

December 24, 2011

As long as there are memories like these, and people like you to tell about them, there’s hope. Merry Christmas, Charles. 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 30, 2011

What a perfect comment, Diane. Thank you. Have a wonderful new year.

LikeLike

life is a bowl of kibble

December 24, 2011

This is the best Christmas story I have read so far. And for some unknown reason it made me cry. Maybe it was the innocence of a child or the no-nonsense of an adult. For whatever reason, it was priceless to me. Merry Christmas

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 31, 2011

I’m glad there was a connection, and equally sorry it’s taken me a week to respond to your comment. Thank you for your kind words.

Happy New Year!

LikeLike

Marusia

December 24, 2011

Wonderful! May your Christmas Day, tomorrow, bring unforgettable and beautiful experiences like the ones you’ve described here!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 31, 2011

Thank you, Marusia. I hope your Christmas was wonderful, too, and that the new year finds you healthy, happy, and writing!

LikeLike

Arindam

December 25, 2011

Simply brilliant. !!

You are not alone while thinking so. At least, I hope there is. There’s something about all of us that’s still alive, and still possible.

Merry Christmas to you!! 🙂

LikeLike

Arindam

December 31, 2011

Wish you a very happy new year!! May this coming year will bring lots of happiness, joy & peace in your life. 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 31, 2011

Thank you, Arindam. Your relentless optimism and goodwill are refreshing — and encouraging. Happy New Year, my friend!

LikeLike

Allan Douglas

December 25, 2011

As always, Charles, an entertaining and poignant piece. I especially liked this”

“For those few minutes that night, it seemed possible that we might all get past those destructive behaviors and realize that we shared this small planet, and that we’d be better off if we could just treat each other with tolerance and respect. The promise of Christmas, the returning light marked by the winter solstice, and the coming new year seemed, at least to me, to be brimming with hope.”

Merry Christmas to you, my friend

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 31, 2011

Thank you, Allan. I hope Christmas was a wonderful time for you and Marie. It’s been truly great getting to know you (and her, indirectly) this past year.

LikeLike

Val

December 25, 2011

I love the image of you sitting on your own absorbed in the space broadcast and your family, oblivious, doing what families do, elsewhere. Children are often so much more in tune with reality than their parents think.

Happy Christmas to you and your family, Charles.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 31, 2011

I don’t remember if I knew the broadcast was coming on, or if it just happened to catch my ear at the right moment. But I’ve never forgotten the feeling it gave me as I listened.

Thank you, Val, for all of your comments and good wishes. I look forward to seeing your updated blog, and for many wonderful visits there in the new year.

LikeLike

Govind

December 25, 2011

A brilliant post for the season. A merry Christmas to you, your family and all your readers. Let us hope that 2012 will be an excellent year for all of us.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 31, 2011

Thank you for your Christmas wishes, Govind, and I agree completely with your hopes for the new year.

LikeLike

perspectivesandprejudices

December 25, 2011

Beautifully written. Merry Christmas and a very Happy New Year to you and your family!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 31, 2011

Thank you very much, and the same to you!

LikeLike

thesubwayspoet

December 26, 2011

Beautifully written and gives me pause to thinks which is much better than a pause to cram more into my gullet. I wish you and yours the best for the holiday and new year

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 1, 2012

If I gave you a little something to think about, it was well worth the effort. Thank you for the kind words. Happy New Year to you, too.

LikeLike

Mal

December 26, 2011

Just goes to show how observant a child is… Thanks for sharing.

Season’s Greetings!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 1, 2012

Thank you, Mal. By the way, I really liked your newest post, and meant what I said: I think you should re-publish it once a month.

LikeLike

She's a Maineiac

December 26, 2011

I finally had a moment to read and savor your latest post, Charles. Simply wonderful. Merry Christmas to you and yours.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 1, 2012

Thank you, Darla. I hope your Christmas was everything you wanted it to be, and the same goes for this entire new year. And thank you also for all of the amazing posts you wrote in 2011. I know there’s a lot more coming.

LikeLike

Misha

December 26, 2011

Beautiful post. I hope that those things are still possible.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 2, 2012

I do, too, Misha. Thank you, and Happy New Year.

LikeLike

winsomebella

December 26, 2011

There is still some spirit in those ghosts of the past and how you have made me feel that. Loved the Apollo clip……and I remember, now, how we were in awe. Lovely post–thanks.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 2, 2012

Thank you, Bella, not only for reading and for the thoughtful comment, but for your amazing blog, as well. Your most recent post was the perfect transition from the old to the new year:

http://winsomebella.wordpress.com/2011/12/30/tick-tock/

LikeLike

ConfusedDi

December 26, 2011

Thanks for a brilliant story and merry christmas!!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 2, 2012

I hope your holidays were great, ConfusedDi. Happy New Year!

LikeLike

dearrosie

December 27, 2011

Belated Christmas greetings Charles.

I lay in the dark in my bed to listen to the moon landing. Whether it was the tinny sound of my little portable radio, or the excitement of men actually speaking from the moon, I don’t remember that they read from the bible. I’m also glad you included the video.

When you woke up and saw your Dad leaving presents under the tree you weren’t disappointed because now you knew Santa Claus’ secret identity! Lovely.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 2, 2012

There was something about the incredible sense of connection, Rosie. This idea that many millions of people all over the world were listening to the same words being spoken by three men orbiting the Moon. It may mean that I’m old, but I’m glad I was around to hear it as it happened.

Happy New Year, my friend.

LikeLike

bigguyblogger

December 27, 2011

I’m finally getting around to reading your post. I thought Christmas was over. Thanks for bringing it back one more time in only the way you can. Perfect!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 3, 2012

Thank you, Big Guy. I’ve been enjoying your blog — and the sideways conversations between you and Mrs. Big Guy. I hope this new year is a great one for both of you.

LikeLike

javeriyasayeedsiddiqui

December 27, 2011

really enjoyed reading the post! 🙂

the little you sounded so adorable especially the thought about the vampire!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 3, 2012

I’m not sure about the adorable part, but I definitely had some strange thoughts.

Thanks for the comment, and Happy New Year!

LikeLike

happykidshappymom

December 28, 2011

Morning, Charles! Let’s see if I can get my comment to post this time. I wanted to let you know I awarded you the Happy Blog award! 🙂 http://wp.me/p1jBAi-yc

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 3, 2012

Melissa, you’re too good to me. Thank you. But I guess I can’t write a crabby post to go with the award. This may take some time.

Happy New Year!

LikeLike

Melinda

December 28, 2011

Everything did seem better back then. I remember wanting the snow cone maker so badly. That was a rich kid’s toy. 🙂 Then years later I got one! I was so excited, and then so disappointed. It was so slow to crush the ice that it all melted by the time you could get near filling the cup. Aurgh! The reality wasn’t the same as the imagined toy sitting high on the pedestal.

LikeLike

Melinda

January 2, 2012

FYI I nominated you for the Versatile Blogger Award. I know you have received it many times…you are just that good. I have my sister loving your blog now. Happy New Year!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 3, 2012

That’s what marketing is all about, and always has been — getting you to think something is better than it really is. The anticipation does usually seem better, doesn’t it? I wonder if we’ve learned the lesson.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 3, 2012

Thank you, Melinda, for the award and for persuading your sister to read my nonsense. I appreciate your writing and your insights, as well as your friendship. I hope 2012 is a great year for you.

LikeLike

android developer

December 29, 2011

Hi Charles! I used to be like this also. But years have passed and my Christmas ideas have changed. The spirit is still there but the practices are no longer the same.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 3, 2012

I think you’re onto something, A.D. You’ve managed to hold onto the true spirit without getting sucked into the madness. Glad to hear it!

LikeLike

earthriderjudyberman

December 29, 2011

How refreshing to read your story about Christmas and your family. I’d read some posts – in the news – about people griping about what they got for Christmas. Like you, I also wished for those more innocent times. Less grabby times, it seems.

LikeLike

earthriderjudyberman

December 29, 2011

BTW, loved the video, too. Thanks, Charles.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 3, 2012

Thank you, Judy. I’ve watched the video about ten times since I found it. What a great moment that was. We seem to have temporarily lost our way since then, but there’s always hope.

LikeLike

Wendy

December 31, 2011

Hi Charles! I’m new to your blog — Hopped right over from Melissa’s Play101 blog award post. Your post brings back so many childhood memories. I never caught my parents placing gifts under the tree, but I sure did try. My brother and I once went treasure hunting for the gifts we were sure our parents were hiding in the house but we never found them. We even stayed up to spy on Santa but we fell asleep for a few minutes before our alarm woke us up (10 minutes later) to a tree full of gifts. Blast!! We had JUST missed him!

Now I’m a mom. My little girl just turned 4 and my husband and I do things a little differently. To be honest, we don’t know what we’re doing. We tell her the truth when she asks us questions. Santa came up when she was told he was real by my sister. Our answer, when she asked us if we could confirm this (because she has always believed it to be just a story), was to remind her of one of her favorite stories – Rapunzel. It’s a great story but that’s all it is, a great story. Every time she asks for more information (I guess she’s checking her facts) we end up at the library to dig a little deeper into the story she’s questioning. I really hope I’m not screwing her up by telling her the truth. How silly does that sound? I do the best I know how. She’s my only child and I want her to have happy memories — A life full of facts can be fun.. right? 🙂 Of course!

The video, by the way, is one I haven’t watched before. Thank you for sharing that.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 3, 2012

Wendy, thanks for the great comment. I don’t know the best way to handle these things, and I guess it varies with different children. I told my son that Santa was real in the same way that Mickey Mouse is real. He seemed to like that idea.

By the way, I loved this post you wrote about your daughter. I think others will appreciate it, too.

http://chaotictea.com/2011/12/09/celebrating-3/

LikeLike

Vinicius

December 31, 2011

Did you made this draws?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 31, 2011

The original artwork for the cartoons was done by a talented man named Ron Leishman. His website is:

http://www.toonclipart.com

LikeLike

eileeneldred

December 31, 2011

Catching up with my blog readin and so, so glad I caught this! Exquisite, moving, funny, thoughtful…wow! Thank you for sharing the video, too. I remember gasping at the sight of Earth from space – even now, it’s gorgeous!

Have a Happy New Year! 😀

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 3, 2012

Thanks, Eileen. I agree with you about the photos of the Earth from space. Maybe we need to retrieve that perspective.

I hope you have a happy new year, as well.

LikeLike

Jessica Sieghart

January 1, 2012

How did I miss this?! What a memory you have, Charles. (Along with a spectacular ability to make us feel as if we are sitting right in front of that black and white box watching the astronauts with you). I remember when I realized my dad was Santa Claus. We’ve always opened all of our gifts and had a large celebration the night of Christmas Eve. (I’ve been told it’s a German thing, but I don’t know for sure). Anyway, we would go to my grandmother’s house for dinner and when we returned with all the relatives for “coffee and dessert”, the living room would be filled with gifts. One year I realized that my dad always forgot his keys and had to go back into the house to search for them while we waited in the car. I brushed it off as coincidence, but when it happened the next year, I must say, it was a bit disappointing.

I’m sorry you never got your Sno-Cone maker. I always wanted the Barbie swimming pool. My dad told me to use one of my mom’s plastic mixing bowls-not the same thing.

I am a little surprised you could put down a Tickle Me Elmo. Ours still makes me laugh. That’s one thing that was worth the price tag, I think 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 3, 2012

Melinda’s description of the Sno Cone Machine confirmed my suspicions — the reality was nothing like the advertisements’ claims. I’m sure I didn’t miss a thing. As for the Barbie swimming pool, I imagine the novelty of that would’ve worn off pretty quickly, too.

Thank you, as always, for taking the time to read, comment, and share your memories, Jessica. I look forward to another year of your great columns. As long as you keep writing, I’ll keep reading.

http://mortongrove.patch.com/articles/he-s-making-a-list

LikeLike

Priya

January 2, 2012

I read this post when it was freshly out of the mint. And it warmed and distressed me all at once, so I decided to stay away and come back later so that I could speak less of the distress.

But first, the loveliness of it. The gift you gave your grandma is an image in my mind that’ll never go. If I have to think of pure love, I’ll think of a purple brush and a comb set. Your stories from your childhood are just the kind a being needs to continue to have hope, faith, happiness.

There are, however, so many who’ve given up on the idea of festivities and good times at a particular time of the year because it is either too much work, or indulgence in unnecessary capitalism, or a blind following of unreasonable tradition that it becomes ever more difficult to see today’s children getting a similar stash of wondrous memories to carry with them to old age.

There, that’s concise.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 3, 2012

Concise and wonderfully insightful, Priya. I think the distress happens when we allow ourselves to be pulled along against our better judgment by what we perceive to be society’s expectations. If we can just relax a little and allow our natural tendencies to guide us, our children will have more than enough wondrous memories to take into adulthood. I’m sure yours will.

LikeLike

Stacie Chadwick

January 4, 2012

I stumbled on your post from a blogroll, that was linked to the topics page, which was a subset of freshly pressed. All in all not the most direct path, but the extra effort was well worth a little less sleep. Your essay is lovely, a wonderful way for this newbie blogger to end the night.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 4, 2012

Thank you for making the effort, Stacie, and for the kind words. I just read one of your posts and loved it. Your writing style and sense of humor are a wonderful combination. I know you’ll find this blogging community to be welcoming and supportive, and I hope you’ll continue — for your sake and for all of ours.

http://staciechadwick.wordpress.com/

LikeLike

icedteawithlemon

January 8, 2012

I have been so busy of late and have been remiss in reading your blog–which I regret because you are such a masterful story teller with the uncanny ability of always, always, bringing a smile to my face. What a lovely post! I especially enjoyed the paragraph about the astronauts and Christmas 1968, and thank you for the accompanying link! Merry (belated) Christmas to you, and I look with anticipation to all your posts in the coming new year …

LikeLike

bronxboy55

January 15, 2012

Thank you, Karen. I hope your holidays were great, too. Happy New Year. I can’t wait to read about this next phase in your life!

LikeLike

Melissa

June 11, 2012

Its almost Christmas again, whew! Time really goes so fast,

Unfortunatelly things have changed, now the message would goes something like this: In the begining a singularity begun to expand or exploded, they don´t even agree on that…and some billions years later, here we are as product of a Big bang, which according to S. Hawkings God is not needed at all…

Melissa from abri de jardin en PVC

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 25, 2012

Thanks for your comment, Melissa. Sorry it’s taken me several months to acknowledge it.

LikeLike

mcgulotta

August 25, 2012

That is a beautiful post and I know who you were referring to when you talked about your father’s cousin.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

August 25, 2012

That cartoon kind of looks like him, doesn’t it?

LikeLike