During a recent car trip up and down the East Coast of the United States, I found myself sitting in frequent bumper-to-bumper traffic. Much of it seemed to be caused by nervous drivers who no longer trusted their own reflexes, and who kept one foot on the brake at all times. Often accompanying these hours of glacial progress were the taunting lyrics to a song that advised you to “dance like it’s the last night of your life.” This was a long journey, and radio stations were coming and going with great frequency, so I got to hear the song — I’m estimating here — about fifteen thousand times. I’d somehow tuned out the endless car dealership commercials and the many heartfelt wishes for a Happy Thanksgiving, but those relentless words managed to work their way to the surface of my conscious mind.

During a recent car trip up and down the East Coast of the United States, I found myself sitting in frequent bumper-to-bumper traffic. Much of it seemed to be caused by nervous drivers who no longer trusted their own reflexes, and who kept one foot on the brake at all times. Often accompanying these hours of glacial progress were the taunting lyrics to a song that advised you to “dance like it’s the last night of your life.” This was a long journey, and radio stations were coming and going with great frequency, so I got to hear the song — I’m estimating here — about fifteen thousand times. I’d somehow tuned out the endless car dealership commercials and the many heartfelt wishes for a Happy Thanksgiving, but those relentless words managed to work their way to the surface of my conscious mind.

“The last night of my life?” I thought. “Dance?”

I don’t know about you, but if it were the last night of my life, I don’t imagine I’d feel much like dancing. I’d probably prefer to spend the time doing something more constructive, like howling in despair or repeatedly hitting something with a crowbar. Besides, how would I know it was the last night of my life? I’d have to be extremely sick to be hovering that close to death. Would I be up to hovering and dancing? The two seem mutually exclusive. And if I wasn’t sick, that would mean I was going to die by getting run over by a train, or being hit by lightning, or finding myself in the crossfire of a gang war. There would be no time to dance, and if there were, I’m not sure how it would help or if it would even occur to me. Running might be more beneficial.

Still, this notion of being aware that you’re at the end of your life has always intrigued me. In Catholic school we were taught that God had a book, and in this book were inscribed our names and the exact dates of our death. Or something like that. I never got the whole story about anything when I was a kid, which always left me trying to piece together answers to big questions with just a few raggedy strands of information. There was a book, that much I was sure of. There may have been two books: one for those going to Heaven, and the other for the rest of us. Long before Judgment Day, apparently, our fate had already been recorded, which was somewhat disturbing. But it was the word inscribed that both confused and scared the daylights out of me. I remember wondering why God would need books. Was it an indication of an overworked all-powerful being? Did it mean there was some possibility for a clerical error? Could something be erased from one book and inscribed in the other? I had this actual thought: “Maybe God writes in pencil.” And most important, where were these books, anyway?

We would never see the books, and therefore had no way of discovering what they contained or where we were headed. Which now makes me think of the person waiting on death row, that rare individual who knows when he will die, maybe down to the precise minute. And that idea of the final dance reminds me of the condemned man’s last meal, served just hours before his execution. Again, would I feel like eating if I knew that I’d soon be strapped into the electric chair or given a lethal injection? I tend to lose my appetite if a bug hits my windshield. I imagine the warden standing over me, demanding that I stop playing with my food, the way my third-grade nun insisted that we eat those hideous green beans because there were children starving in some far-off place. She was stationed at the spot in the cafeteria where we emptied our trays, which gave her a chance to effectively scrutinize any leftovers on our plates. We devised counter-strategies, of course. These included secretly passing food under the lunch table to Marvin Pierce (who would eat anything), and when he wasn’t available, stuffing beef stew into an empty milk carton and learning to toss it with minimal splash.

But there’s slightly less privacy in prison. What must it be like to know that what you’re eating, hearing, and looking at will be the last experiences of your life? And if you had the choice — beyond the final meal — what would those experiences be? I’ve heard of people who, dying of a rare disease, worked like crazy to complete their law school degrees. Others take their dream vacation or finish writing a novel or start trombone lessons. But really, how do you relish any accomplishment when you know it’s your last? How does that thought not seep into, and contaminate, every moment of potential joy?

I understand that the song isn’t necessarily talking about dancing in the literal sense. It’s saying we should live each day as though it might be our last, that whatever we’re doing, we should do it with passion and enthusiasm. I just don’t think that attitude works for me. I need something to look forward to. Also, I’ve been around passionate people and they tend to talk loud, which after about an hour makes my skull vibrate. When I’m the one being enthusiastic, I usually start moving too quickly for my own brain and I end up with some self-inflicted injury, like when I pull hard to unplug an electric cord and punch myself in the mouth.

I understand that the song isn’t necessarily talking about dancing in the literal sense. It’s saying we should live each day as though it might be our last, that whatever we’re doing, we should do it with passion and enthusiasm. I just don’t think that attitude works for me. I need something to look forward to. Also, I’ve been around passionate people and they tend to talk loud, which after about an hour makes my skull vibrate. When I’m the one being enthusiastic, I usually start moving too quickly for my own brain and I end up with some self-inflicted injury, like when I pull hard to unplug an electric cord and punch myself in the mouth.

I’ve behaved impulsively many times in my life, and it rarely works out. It’s better if I slow down. In fact, sitting in bumper-to-bumper traffic is the safest place for me. It gives me time to think things through, to make decisions with no possibility of acting on them, and then more time to think again.

But sooner or later I’ll realize that my days are numbered. That’s one of the reasons I’m looking forward to driving when I’m very old. I have no intention of being like the other elderly motorists I see on the road, inching out of parking spaces, resting their foot on the brake pedal, and plodding along at twenty miles under the speed limit. I’m going to plaster a big sign on the side of my car that says, “My reflexes are totally gone. Watch out.” And then I’m going to drive to Florida and back as fast as I can, with the radio blasting and dancing behind the wheel like it’s the last night of my life. And if that causes my name to be inscribed in some book somewhere, well, it sure beats hovering. Or getting run over by a train.

life is a bowl of kibble

December 5, 2011

I would love to dance everyday. That way when my time comes I could say I had a great ride. However, life has a habit of getting in the way.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 6, 2011

You write about life and its habit of getting in the way. Maybe that’s your dance.

LikeLike

She's a Maineiac

December 5, 2011

So I’m not the only one who punches themselves in the face when removing a cord? I’ve got to slow down. But I like to live my life on the edge. (I’m super klutzy so that helps)

Thank goodness for being stuck in traffic, or else you’d never have time to think up these hysterical, brilliant yet poignant posts. Who else can use the tags, death and hell and make it funny?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 6, 2011

Darla, I should start keeping track of the number of times each day that I hurt myself. Just in case someone is ever asked to explain the bruises.

LikeLike

Diane Henders

December 5, 2011

LOVE your idea of the signs for the car! Sounds like a wonderful trip, but why wait until you’re old? Why not do it now? You know, in the spirit of living in the moment and all. ‘Course, I guess theoretically that might move up the whole “last-day-of-life” thing.

The signs may attract unwanted attention from those humourless law enforcement types, though, so here’s an alternative. Back in the days when I drove a rust-bucket 1975 Dodge Dart, I discovered I could drive anywhere, any-how. The drivers of shiny new cars just got out of my way. They knew I had nothing to lose.

I still have an old rust-bucket 1980 half-ton, if you want to borrow it. 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 6, 2011

I keep telling my son that driving is mostly about thinking, and some of us have to do extra thinking to make up for the ones who don’t do enough. That 1980 half-ton would certainly help relieve some of that pressure. Thanks, Diane. I just might take you up on your offer.

LikeLike

Ann-Marie Allin

December 5, 2011

I just realized in the past two or three years that I love to dance! I am 51 years old I love Zumba and Bellydancing and would love to be able to dance like Shakira and Beyonce, all the while I am trying to remember that I am 51 (no matter how good the beat is) and of course that they have drs and medical personnel with them at all times and I dont!’) But even so I intend to continue to shake my groove thang (that is as long as I dont’ sprain or break it, which is a distinct possibility at this time) until the day I die!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 6, 2011

You’re still young, Ann-Marie, and I bet dancing will keep you young for a long time. I’m glad to hear it.

LikeLike

oolung

December 5, 2011

As always, a funny and wise post. I don’t quite buy into the idea of “living as if each day was my last” (in the popular sense of “living to the full”). Does it apply to the days when I have to deal with my country’s post-communist red-tape or a broken printer, too? I dare anyone to say it does… Be it as it may, I was recently delighted to find this little quotation: “This is the mark of a perfect character, to pass through each day as if it were the last (…wait for it…!), without agitation, without torpor, without pretence” (Marcus Aurelius). Might it be the original source of the saying? If so, how ironic that the crucial part has been chopped off in usage…

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 6, 2011

It sounds as though Marcus was saying we should avoid the things we may later regret by doing it right the first time. Easier said than done, though, especially when you get tangled up in that Chinese red tape. Or any other kind, for that matter. Speaking of China, I loved this recent post of yours:

http://downthedragonhole.wordpress.com/2011/12/04/the-box-of-goodness/

LikeLike

ceciliag

December 5, 2011

make sure you have a clean pair of undies on for the Florida trip!! Oh and sadly I am one of those people who actually really and truly don’t LIKE to dance, i am more of a drinker, when people try to MAKE me dance and this has been tried many times before, I shall tell them from now on that ‘this is the last day of their lives and Go dance with Someone Who Cares!!’ c

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 6, 2011

I think refusing to dance when all around you are dancing their fool heads off is your right. It may even be your own form of dance. But does it really make you feel sad?

LikeLike

Patti Kuche

December 5, 2011

It all sounds like purgatory to me. Love your Dylan Thomas road trip!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 6, 2011

Thanks, Patti. I will not “go gently into that good night.” And if I do, I’m certainly not paying the toll.

LikeLike

Melinda

December 5, 2011

I would probably spend my last 6 hours trying to figure out how to spend them and waste them away. I guess dancing sounds better than that. Plus I want 3 giant Starbucks Caramel Macchiatos and a large box of assorted Godiva chocolate. With that much caffeine the dancing will come naturally. 🙂 Awesome story as always!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 6, 2011

I can never remember: is Giant their large size, or is there something even bigger? I’m afraid I would spend much of my last day trying to figure that out. And what does it say about us that we’re wasting time now worrying about how we would waste our final hours?

LikeLike

The Sandwich Lady

December 5, 2011

Loved your reminiscences about God’s book. My personal favorite scary memory of Catholic school was the nuns telling us about the Last Judgment, when God would read aloud all your sins for all the world to hear. Your writing continues to inspire!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 6, 2011

I was always confused about that Judgment Day thing, because it seemed that people went directly to one of the three places immediately after they died. So why the need to make a public display of everyone’s sins again at the end? And would the souls going to Heaven really be required to sit through all of that? It would be like having to go through airport security for a million years on your way to Disneyland.

Thanks, Catherine.

LikeLike

Arindam

December 5, 2011

Great post with a great thought. I do not like living my life as it going to be the last day of my life. I do not want to live my life on the basis of a moment or a day. For me life is like an endless road, and i will enjoy this journey without much caring about the destination.In this journey i will love to enjoy everything that is going to come my way.

If i can know it’s my last day of my life, how can i dance knowing that some of my dream are not going to fulfill in this birth of mine, i can’t be with those close people anymore whom i love and care. Rather than dancing, as a writer may be i will keep a notebook & pen with me, so that may be i can write something like “I am dancing, because i have no other job to do… as yesterday was the last day of my life”. 🙂 But yes only if god will permit me to do so.

Your posts always makes me think, although i am not sure whether i think in the proper direction or not. Sir Charles this time i am not even going to say i liked this post of yours. This time i am only hitting the like button on this post of yours. I am now feeling that it’s needless to say i like this post of yours. 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 6, 2011

You are a writer, Arindam, and I have a feeling (and the hope) that you’ll be writing your heart out right up to the very end.

LikeLike

Arindam

December 7, 2011

Thanks 🙂 yes i will for sure!!

LikeLike

magsx2

December 5, 2011

Hi,

Don’t you just love being stuck in traffic, the mind always goes elsewhere, and sometimes the smallest of problems can be solved this way. 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 6, 2011

I agree, Mags. Although it’s a little unsettling when I realize I’ve just driven eighty miles, gone over a bridge and through a tunnel, and I don’t remember any of it.

LikeLike

delajus

December 5, 2011

I recently tried to use a writing prompt that went: “You have one week to live. How do you spend the time?” Interestingly enough, I gave absolutely no thought to heaven or hell or even purgatory. I went directly to the answer that I knew was true and, therefore, unavoidable. I would spend the last week of my life eating every Hostess Ho-Ho I could lay my hands on. Ding-Dongs would do in a pinch. If I’m fat in the afterlife– wherever that may be — well, then I’m fat. Thanks so much for another hysterical, yet profound post. I enjoy your work so much!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 6, 2011

I like the idea of having a week to live. Being told it’s your last night creates too much pressure to make it meaningful, but I could probably come up with something in seven days. I imagine there’d be a few Twinkies in there, too.

I enjoyed your recent post:

LikeLike

Boy Mom Blogger

December 5, 2011

there’s actually a book I read about (didn’t read it though) that talks about how to spend the last year of your life. so I was in this frame of mine recently too! I like to think during long road trips too – sometimes I even turn the radio off to ‘hear myself think’ 🙂 great post again ….

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 7, 2011

I like long road trips, partly for the same reason. They take away a lot of the distractions and noise in my head. But then I always wonder what I’d been thinking about the rest of the time — when I wasn’t paying attention.

LikeLike

patricemj

December 5, 2011

You are so funny. As your reflexes one day leave you, my prediction is you’re just going to get funnier and funnier. And a little more dangerous. Can’t wait for that.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 7, 2011

You wouldn’t be saying that if you had to share the road with me.

By the way, I’ve been trying to email you, but the messages keep getting returned. There’s been a problem with images on some WordPress blogs (yours and mine, to name at least two). Go here to get it fixed:

http://en.forums.wordpress.com/topic/wp-changed-format-of-my-pictures-why/page/8?replies=184

LikeLike

MJ, Nonstepmom

December 5, 2011

I have had this anxiety attack: somehow I am given the knowledge of my hours remaining, I make the decision how to spend the time, but then find myself stuck in traffic/ on an airplane waiting for clearance…..why do we torture ourselves with things we can’t control? Great post again!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 7, 2011

I think the self-torture comes from the realization that most of us have been given hundreds of thousands of hours over a lifetime, yet we don’t see the value in each of those hours until we have only a few left. I’ve come to understand this idea over and over, and then I forget it again, sometimes for years.

Thanks for the comment, MJ.

LikeLike

Carol Deminski

December 5, 2011

You raise a really important question here – how is it that radio stations conspire with one another and you hear the same damn song on the radio over and over and OVER again from New York to Miami. Sheesh.

I love “classic” rock (that means we’re old, by the way) or “lite” music (which I think is a bit like non-food-cheese-product) or “smooth jazz” (again, that means we’re old) as much as the next girl, but imagine what your car ride would have been like if you heard… I don’t know, Don McClean’s “American Pie” 72,000 times, or maybe Pink Floyd’s “Run” or Zepplin’s “Stairway to Heaven,” or the Doobie Brothers “China Grove” or anything but that dreadful song you quoted.

We’re all going to have to chip in and buy you that 8-track-cassette player you’ve been asking for so you can control the music, and the thoughts, in your car….

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 7, 2011

I’ve wondered the same thing about the radio stations, Carol. Where I live, a concert given by a major star is a huge thing, and it’s all they talk about on the air for months. And suddenly that star’s music is played every hour, leading right up to the concert. Here’s the question I always ask: “Is that performer being paid a royalty every time a song is played? If so, not only is his concert being publicized for free, but he’s being paid for that publicity! How do we get in on this?

Also, I have the eight-track player, but the stores have suddenly stopped selling the tapes.

LikeLike

souldipper

December 5, 2011

Seniors in my Province buy license plates that depict them as seniors. I used to wonder why on earth they would ever want to declare their “oldness”.

Aha…now I know. Everywhere they go, other motorists stay right away from them. It’s as if there’s a bubble around them that no one can penetrate…on roads, in parking lots, by crosswalks. They don’t need any other sign!

What’s on these license plate? It’s hard to read through the zigzag motion, but I think I saw “Terror”. A small halo rests over the “o”! 😀

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 7, 2011

There are probably designated parking spaces for seniors, too, and they need the special license plates to park there. I’d never want one — if I got privileges, I’d have to feel guilty about my reckless behavior.

LikeLike

S. Trevor Swenson

December 6, 2011

Remember the car radio/cassette players that could be removed and taken with you when you locked up your car, often coupled with the “No Radio” sign in the window ( Yeah signs are the ultimate deterrent to theft”

During the 80s and 90s I ofetn suffered radio rage where upon hearing an annoying song for the 50th time in a day, I would have to fight the urge to pull the radio out and jettison it through the moon roof or window.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 8, 2011

I remember thinking what a pain that must be to have to remember to take your radio with you, or lock it up in the impenetrable glove compartment. (They’ve broken into your car, but they’ll never get through that locked section of dashboard.) Have you tried audiobooks? It’s the best thing I’ve found to prevent radio rage.

LikeLike

Barb

December 6, 2011

I still love Martin Luther’s answer when asked what he’d do if this were his last day on earth….plant a tree.

LikeLike

patricemj

December 6, 2011

You can never go wrong planting a tree!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 8, 2011

That takes care of the morning, but then what?

LikeLike

rangewriter

December 6, 2011

So if I got out into west Boise more, got stuck in the traffic out there, perhaps I’d have time to think up wonderful posts like yours? Na. I doubt it. I love your “final solution” to senior driving. You realize that your kids will have hidden your keys and you will only THINK you’re zooming off to Florida?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 8, 2011

No, I think my kids will hand me the keys and a road map, and buy me the first tank of gas.

LikeLike

myonepreciouslife

December 6, 2011

Yeah, I wouldn’t spend my last day dancing either. Or getting a law degree. Seriously, you’re told you have six months left and you decide to spend it at law school? Really?

Oh, and I grew up in a town where a lot of people retire and there were plenty who drove the way you describe. It was terrifying and I strongly think people should have to get re-tested for their licenses every five years from the age of sixty.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 10, 2011

And what if I spend my final year at law school, and then on my very last day of life, I find out that I failed the bar exam? That would kill me.

Speaking of tests, I agree with you about the driver’s license thing. But I think there are a lot of people out there who need to be retested, and it has nothing to do with age.

Thanks for the comment, Stephanie.

LikeLike

myonepreciouslife

December 11, 2011

You’re probably right. Must work on correcting my ageism.

LikeLike

writerwoman61

December 6, 2011

I love this, Charles! I love to dance, but my children find it tremendously embarrassing (which is why I endeavour to do it in front of their friends whenever possible).

In all seriousness, I do try to live each day to the fullest, despite any self-inflicted injuries that occur (like the other day when I smacked myself in the mouth while closing the medicine cabinet door…I was distracted by something one of the kids had left where it wasn’t supposed to be!).

Wendy

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 10, 2011

So other people smack themselves in the mouth, too? At the risk of sounding a little sadistic, I’m glad to hear that. I’m also glad to hear from you, Wendy. We’ve been out of touch. I hope all is well.

LikeLike

writerwoman61

December 10, 2011

I’ve just been working, a temporary job which is now finished. Sorry I haven’t made it over to the Island yet this year! It will probably be spring now before I get there…

Happy to be back in Blogland!

Wendy

LikeLike

happykidshappymom

December 6, 2011

The idea of the last dance. So tragic. Yet I do subscribe to it. I can see where you’re coming from (punching yourself in the mouth with electrical cord whiplash), but for me, I tend to live like I’m out in front of the gun. One way cannot trump the other; we each believe what we believe.

It’s important to ponder these issues, every now and again, and I thank you for putting it forth with such humor. Last dance or not, smiles carry us through every time.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 10, 2011

Thanks, Melissa. Your comment made me think, again, about how flat and rigid it’s possible for me to sound when discussing almost any kind of philosophy of life. My feelings or beliefs aren’t necessarily consistent from year to year, month to month, or even day to day. Yet when I write about them, I may give the impression that I’m completely locked in. The truth is, I have no idea what I’d do if I knew I had a specific amount of time left. Even during those final few minutes, I’d probably change my mind once or twice. I agree with you about humor and smiles, though. It’s the only way to go.

LikeLike

myonepreciouslife

December 11, 2011

I love this comment. It more or less sums up my approach to everything I’ve ever thought or said or done.

LikeLike

happykidshappymom

December 11, 2011

Flat and rigid? Are you kidding me? One reason I enjoy your blog so much is that you write with confidence. I don’t view it as “locking yourself in,” but rather, picking a point and sticking with it. Giving me something to think about. A clear direction. Even if it’s just for the moment, as you say. I hope you don’t think I view you as Mr. My-Way-Or-The-Highway. Your writing, to me, is like a series of snapshots. Each post shows a particular view of the world, presented with humor and depth. That’s a treasure, not a trap.

LikeLike

worrywarts-guide-to-weight-sex-and-marriage

December 6, 2011

Great post. I hate songs about the last day of one’s life. I always turn them off. I’m a worrywart so I spend every moment like it is the last moment of my life, hence, I have no regrets (except dieting, I really regret dieting). I’m always doing exactly what I want to be doing if it were the last day of my life (which is usually something really safe that won’t kill me).

Coincidentally, I received your book, and read it while in a hospital waiting room. The story at the end sort of worried me because I was waiting for an MRI. I was completely freaked out in the machine because I was worried about an earthquake. The technician had to stop the scan and pull me out. She explained that if there was an earthquake (this is not that far-fetched because the hospital is in San Francisco), I would be in the safest place possible. So I spent the next hour thinking this is where I’d want to be if the Big One hits.

I thought it was sort of serendipitous that I read your book while waiting because even though I feel very confident about what the results will be, I’m not going to waste a moment waiting on the doctor.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 10, 2011

I’d hate to know how much precious time I’ve wasted sitting in waiting rooms. Thanks for buying the book, WW, and I hope it helped pass the time. I also hope the MRI results are good news.

LikeLike

John

December 6, 2011

Another top notch essay. (It’s too good to be called a “post.”) Oh, the stories wrought by a Catholic school education!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 10, 2011

And I think the best stories are the ones I’ve forgotten. I’d go to a hypnotist, but I’m not sure I really want to remember.

LikeLike

Jessica Sieghart

December 6, 2011

On the one hand, living each day as though it’s your last sounds nice, but it’s far too freaky to think about on a regular basis. It’s funny that you mention “the book”. Ever since I heard that as a child, it scared the heck out of me and I can’t even really enjoy New Years because of it. All I can think about on New Year’s Eve is I’m one year closer to the date in the book. I really wish someone would invent selective amnesia pills. The way you and I interpreted those lessons so similarly is almost eerie. Well, I love to dance. Jumping around like a nut on the dance floor would be an okay exit strategy for me 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 10, 2011

Another eerie thing is how much those lessons never completely leave us. Their effects are still there, no matter what we do to rationalize them away.

I hope this New Year’s Eve finds you dancing and happy, Jessica, and looking forward to a year of much less worry and stress. You definitely deserve some smooth sailing.

LikeLike

Nel

December 7, 2011

I like this line very much: But really, how do you relish any accomplishment when you know it’s your last?

Ignorance is bliss in the case of when I shall pass on to the next life. I do believe, however, in taking the meaningful options – which things are worth my time accomplishing. This quote by Stephen Hawking pretty much sums it up for me – “We should seek the greatest value of our action.”

Oh and about that “book”, I was told it’s written in pencil.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 10, 2011

That Hawking quote does say a lot, Nel, and one he must really follow, given the amount of work he produces. Thank you for reading this post, and for the excellent comment.

LikeLike

Jezzmindah

December 7, 2011

I’ve a strong suspicion that my dancing could be the cause of, not only my death, but perhaps also the death of others.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 11, 2011

I think that’s a different song, Jezzmindah: “Dance like it’s the last night of their lives.”

LikeLike

Yulia

December 7, 2011

I think I have to start to learn how to dance, Charles 😀 I can’t 😀

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 11, 2011

Do your two little boys know how to dance? I bet they do, and would love to teach you.

LikeLike

Yulia

December 11, 2011

hahhaha yeah.. they always dance when sing a song 😀 you are right! I will need to learn from them, Charles 😀

LikeLike

kathleenmae

December 7, 2011

I live by this notion everyday. I never used to but life is too short and I think it’s really important to live each day as your last because you don’t know what could happen. God forbid nothing bad does. But I believe in being happy and just taking each day as it comes and doing whatever it is you want to do that makes you happy. I would want to leave this world knowing I was happy and doing something with my life 🙂 beautiful post!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 11, 2011

You’re right, Kathy. This is the only life we can be sure about, and it makes no sense to spend it being miserable — especially if we have options and the ability to pursue our dreams. It does seem necessary to remind ourselves of that every once in a while, though. And that’s yet another benefit of having some blogging friends.

LikeLike

lifeintheboomerlane

December 7, 2011

I found you by way of John at Trask Ave. I can’t live each day as if it were my last because I would be calling all the people I love and telling them that I love them and they would all think I was nuts. And then while this was going on there would be a major consumption of coffee Haagen Dazs and chocolate, which would have really bad consequences. But I can live each day as though my life makes a difference to the planet. And, at the end of the day, I can ask if maybe one person is better off for having had me around. And then I can tell maybe one person I love them and eat a little ice cream.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 11, 2011

That sounds like an excellent approach, Renee. Too many of us, I think, start out wanting to save the world, and when we figure out that we can’t, we give up entirely. Changing the world for one other person is within reach every day. And, hopefully, so is ice cream.

LikeLike

writingfeemail

December 7, 2011

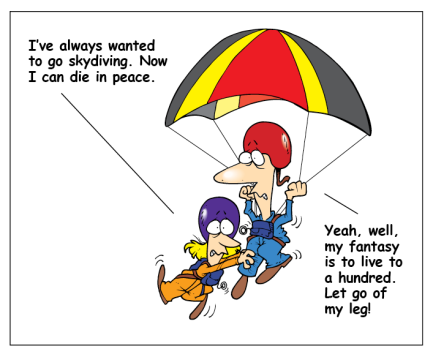

If being stuck in traffic encourages your muse, then I hope you have many more delays. Personally, on the last day, I think I’d like to try skydiving. After all, what would you have to lose?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 11, 2011

Skydiving is a great idea. And you wouldn’t have anything to lose — although the beneficiary on your life insurance policy might.

LikeLike

Snoring Dog Studio

December 7, 2011

Here again is the brilliance of who you are as a writer and as a person. Your self-effacing style is so doggone endearing; it makes me want to hug you. And the writing pulls the reader along over the hills, the valleys, around the bends – we all go so willingly because we love the journey with you! You are a brilliant humorist, my dear friend. Don’t ever stop writing.

I never think much about the question you pose. But my answer would be that I’ll be doing whatever it is I’ll be doing. I wouldn’t want to alter my behavior in any way. I’d hope that by that day or night, all the people who need to know I love them dearly, will have known.

I bought your book, Charles. I’m giving it as a present to my brother-in-law because I know he’ll appreciate your charming tales and your delightful writing style. And then, I’ll have to buy my own copy!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 11, 2011

Thank you for your unfailing support and loyalty, SDS. You’ve taught me a great deal about writing, friendship, and life. We haven’t met in person, yet, but I’m pretty sure we will. Please save up those hugs.

And I loved your most recent post:

http://snoringdogstudio.wordpress.com/2011/12/11/finding-the-seasons-spirit/

LikeLike

arborfamiliae

December 8, 2011

One of the most intriguing stories about how someone used their final days in the face of impending death is Ulysses S. Grant’s. Having lost lots of money in failed business deals and scandal, he spent his last year fighting cancer and writing his memoirs. Whether he did this out of a desire to control his legacy or to provide for his family, it seems like a noble and valiant way to spend a final year.

There’s a new book out about it called Grant’s Final Victory. I haven’t read it yet, but it’s on my list.

I hope I won’t know the date of my own death. Some things are better left undiscovered. But if I do, I hope I handle my final days as well as Ulysses S. Grant did.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 11, 2011

Grant is one of those US presidents who’s due for a fresh look. His reputation took a hit because of the scandals that came out of his administration, but he was, in many ways, an admirable man and an excellent leader. Thank you for using him as an example. I think it’s a good one.

LikeLike

earthriderjudyberman

December 8, 2011

I’d probably like to go out either dancing or laughing. One favorite tune is Prince’s “1999.” I recall rocking out to that while I was on an interstate. And, I’m not talking figuratively. The car actually was rocking because of me and others who were in the car bouncing to the music. I’d be a great way to go. And, Charles, I’ll be on the lookout for you on Florida’s highways. Your posts always make me smile.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 11, 2011

I doubt you’ll see me anytime soon in Florida, Judy. But I thought you lived in New York. Either way, thanks for the kind words.

LikeLike

earthriderjudyberman

December 15, 2011

I lived in New York until mid-1999. Then we moved to Florida. I’ve been back to my old haunts in New York several times and this area has my heart more than any other. (The car ride, for example, took place on I-81 in the Syracuse area.)

LikeLike

dearrosie

December 9, 2011

Another great post Charles. SDS expressed my thoughts exactly when she said: “we all go so willingly because we love the journey with you”.

What do those Nuns tell the children about heaven and hell? My Mom, who went to a convent school, lived to be 95 yet right to the end was terrified of dying…

If I knew I had one hour left to live, like those condemned to death, what would I want to do? I don’t think I’d eat one last meal – well perhaps I’d ask for a GROM gelato

and then be so disappointed because I’d be given some chemically colored “stuff”, so thanks, but no thanks to the meal, for my last hour, I’d like to walk outside, see the stars, breathe the fresh air, look at flowers, sit for a few minutes under the trees…

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 15, 2011

I just read your post on GROM, Rosie. It took me about five minutes to get back here, because it had me daydreaming about gelato. I’m with you, though: no eating during those final hours. Looking at the stars sounds about right.

LikeLike

bitchontheblog

December 9, 2011

Charles, if we’d met up in my mother’s womb we’d be twins.

I too would break my toe whilst howling and wielding a crow bar. It’s bad enough to know that any of us could drop any moment. I’d love to know well in advance (say, a year or ten, to organise the debris of my life) but when put into that tight spot of last “day” I’d probably ask to be more precise (are we talking twenty four hours or just till midnight), pour myself some champagne, light a cigarette (I don’t smoke), think it through, feel very happy for all the people who will not know how to cope without me, get onto the phone to pass on the glad tidings and – for once – keep every single conversation very short: Well, Sweethearts, it’s too late now. You had your time and you took it. Don’t bother about the funeral. In fact, I’d probably slink off into the wilderness. Lie down and hope for some scavenging wolves or bears to pass by the next morning. Before the worms and maggots get me. So yes, under the circumstances, dancing seems a bit of a time waster. I’d rather have one last fencing match. Dancing by another name.

U

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 15, 2011

You had me, Ursula, right up until the scavenging wolves. I tend to change my mind a lot at the last minute, and in that case, there’d be no turning back. If I could time it just right, I’d like to jump from an airplane, open my parachute, and die on the way down — in complete silence and with a great view. Of course, if the chute doesn’t open, then the whole thing is ruined.

LikeLike

Betty Londergan

December 11, 2011

Sorry to be a late joiner to the party, but I was busy living as if this were my last day. Not really — personally, I can’t stand that advice. First of all, as you mentioned, it’s impossible. You aren’t likely to know it’s your last day .. and living as if each day is your last would be a totally false way to live. Even if you could summon up all the emotion, frenzy, sorrow and panic that you’d feel knowing you’re a goner, how sustainable would that be? You’d be lucky to make it through 24 hours. Plus, there is something nice and comforting about taking life for granted … it’s a gift to think you have oodles of time to daydream, sit in traffic, get annoyed at your mate, read blogs, etc. etc. I’m personally happy to live as if I have all the time in the world– and I’ll be around to read your wry, insightful, delightful posts forever! Enthusiastically yours, xooox B

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 15, 2011

You’re right, Betty. Pretending we’ll always be here is the best choice. It’s certainly worked up until now. (That’s actually a Stephen Wright joke: “I plan to live forever. So far, so good.”)

LikeLike

Priya

December 12, 2011

Is it all right if I panicked? Just, plain panicked? Yes, that’s what I’d do.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 15, 2011

Panic seems as though it would be a likely response, but that may be the feeling we get when we think about death now, in this moment. If we were actually right up against it, we might feel something else, something impossible to predict. Or, we might panic.

LikeLike

Cartoon Daily News

December 12, 2011

Wonderfully well written!!! Makes me think about my drives to and from Oklahoma to Texas.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 15, 2011

Thanks, CDN. I’ve never been to either of those states, but I imagine that highway experience is pretty similar.

LikeLike

bigguyblogger

December 12, 2011

If I were looking death in the face I would do the Moon Walk.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 15, 2011

And that just might be enough to give him second thoughts.

LikeLike

ailsapm

December 16, 2011

I usually go with Dilbert on dancing: Dance like it hurts, Love like you need money, Work when people are watching. Thanks for the giggle, Charles.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 16, 2011

Thanks for reading, Ailsa. By the way, your recent posts about the trip to Guatemala are wonderful:

http://wheresmybackpack.wordpress.com/2011/12/06/la-antigua/

LikeLike

shamasheikh

December 16, 2011

Wisdom with humor and food for thought again…thank you Charles!

Realizing the importance and value of all the hours we do have…above all remembering them when we fail to be the best that we can…is hard enough…imagining what one would do in the last hours of life is too hypothetical and even more difficult…the angst of not being all one would like to be is a scary and humbling thought…however, living life to its fullest in the moment that is essential, I will however not be blasting and dancing behind the wheel, as I am that dinosaur who does not drive…:)

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 17, 2011

And I’m the dinosaur who doesn’t have a cell phone. Still, I hope we can both avoid extinction for a very long time. Thanks, as always, shamasheikh.

LikeLike

Amiable Amiable

December 20, 2011

‘I’ve been around passionate people and they tend to talk loud, which after about an hour makes my skull vibrate.’ Yes! Have you ever been around passionate dancers? They give me the jitters. And I don’t mean Jitterbugs. I hate dancing, and I couldn’t dance to save my life – like if it meant not dancing would result in the last night of my life.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

December 27, 2011

Do you mean people who like to dance at weddings, or people who dance on the stage? I don’t like the first kind, because they’re always hitting me with their elbows on the dance floor. And I don’t like the second kind, because they have great posture, and then I try to pretend I have great posture, too, and end up hurting my back.

LikeLike

Lindsay

June 21, 2012

Well, yes ~ dancing really makes all you blood circulate since it allows the body to work out and the same time with grace moves. Very nice article as you usual do.

Lindsay from rouleau de papier cadeau

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 21, 2012

Thank you, Lindsay. I appreciate your feedback.

LikeLike