We all have dark, scary places we drag around from our childhood. It may be the basement, or the attic, or Aunt Trudy’s weird doll collection. Or Aunt Trudy herself.

We all have dark, scary places we drag around from our childhood. It may be the basement, or the attic, or Aunt Trudy’s weird doll collection. Or Aunt Trudy herself.

For me, it was the Confessional. The very word still evokes an image in my mind, with attached feelings otherwise reserved for thoughts of the gallows, and the electric chair. Mysterious things happened in that booth, invisible, other-worldly things. It was like a haunted house, only smaller, and with no place to run. More like a haunted broom closet. Or a coffin with extra head-room.

The Confessional itself was made of dark wood and had intricate carvings and thick purple drapes. It was impossible to mistake it for a place of casual conversation. Matters of eternal life were handled in there. And that’s what caused my heart to stop beating for seconds at a time. It was that grim gravity. (Like the bronze bust of Jesus hanging on the wall over my bed. I didn’t even know it was Jesus. I’d glance up and there was this scowling face looking back at me. A head mounted on the wall. A head wearing a crown of thorns. A head without a body. All reasons enough to be scowling, but of course I assumed it was something I’d done.)

The booth was about eight feet long and had three doors. The center section was where the priest sat. On either side were the penitents’ compartments. A single line of confessors fed both sides, with the priest alternating between the two by sliding open and closed a little cloth-covered panel. That way, there was no wasted time, reducing the chances that someone would die on the spot with Mortal Sin still on their soul. Inside the booth, there was a place to kneel, a place to sit, and a light bulb down near the floor in one corner. Because of the confined space, shadows were big, and moved fast and with holy drama. When the priest was talking to the person on the other side, you could hear his muffled words. I could never make out what he was saying, but he sounded close, as though his voice were coming from somewhere around my head. The other person seemed to be miles away, their responses soft and tentative.

I was in the second grade when we made our First Confession. We were seven years old. That may seem young, but this was back in the Middle Ages, when most people were married at ten and dead by twenty-five. By the time you reached seven, you were expected to know right from wrong, understand the consequences of your actions, and be prepared to burn in hell for them. And we had to know the Apostle’s Creed — in Latin — which was the worst part of all. I had trouble remembering my own telephone number. There was little chance I would ever be able to memorize a long, bewildering prayer, especially in a foreign language in which every word sounded like every other word. We were also required to recite the Hail Mary every single day, to beseech the Virgin Mother to pray for us “…now and at the hour of our death.” It was a daily reminder that a time was coming, a specific hour already recorded in God’s appointment book, when we would die. I was affected by speech as much as by anything else, and so even the word beseech seems to have lodged itself in another one of those dark and scary places in my mind. Beseech isn’t part of my everyday vocabulary. I might use it if I were about to be thrown from a cliff or set on fire. But in all other situations, I would just ask politely.

Sins weren’t limited to the acts we committed. According to The New Saint Joseph Baltimore Catechism, “Actual sin is any willful thought, desire, word, action, or omission forbidden by the law of God.” That covered a lot of territory. When I told my younger brother to shut up, that was a sin. When he bit me in the leg and I punched him for it, that was also a sin. But even when I just thought about telling him to shut up — not daring to say the words because the last time he bit my leg, he broke the skin and drew blood — even that put a stain on my soul. Going to Confession on a regular basis, then, was intended to remove those stains, to cleanse the soul and freshen it up, because you just never knew when the hour of your death would arrive.

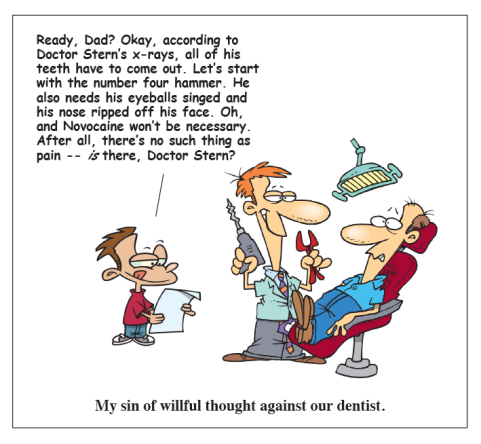

Adding to the haunted atmosphere was the constant presence of God as the Trinity. The Father and the Son were no problem, but that third one, the Holy Ghost, struck fear in me like nothing ever had — nothing except Doctor Stern, the creepy dentist who claimed that the existence of pain was a myth and who often made me wish I could drown myself by pressing my face into his spit sink. If karma is real and includes a system based on any justice at all, Doctor Stern has since left this Earth and returned as a test dummy in a stun gun factory. More than a few of my adolescent sins involved my dentist, the vivid image of some part of his body being pierced, punctured, or drilled, and me offering him a few kindly words of preparation: “Now you’re going to feel a little pressure. A slight pinch. But only a big baby would think it hurts.”

Confessions were held at the back of the church on Saturday mornings. I was careful to list the precise number of times I’d committed each sin, adding another thirty percent on top, just to cover my spotty memory. Even if I’d forgotten some of my sins, I knew God would not, so I gave exact figures, as though I were reporting on the inventory at a hardware store: “I talked back to my parents eleven times, I didn’t eat my vegetables six times, I forgot to say my prayers three times…”

And then, there was the bra commercial.

We had a television in our classroom. It was a big black & white set that sat atop a rolling stand. We’d watch whenever there was a newsworthy event happening, such as a rocket launch or the Pope’s visit to New York. When it was too cold or wet to go to the playground, we’d watch cartoons or some unbelievably dull science show. Our teacher would get two or three boys to haul out the whole setup, push it into the left front corner of the classroom, twist it into position, and plug in and connect any necessary wires. Then she’d give us the warning:

“I have to be out of the room for a few minutes. I expect you to stay in your seats and be quiet. I’ll be right down the hall and if I hear a sound, the television gets put away. Is that understood?”

We’d reply in sing-song unison. “Yes, Sis-ter.”

But somehow, no matter what time it was when that television got turned on, within minutes we’d find ourselves watching a commercial for the Playtex “Cross Your Heart Bra.” It never failed to evoke a circus of whoops and comments. I would look down at my desk, mortified. I didn’t dare make eye contact with anyone, because if I did I’d have to express some reaction to the fact that we were looking at a woman in her underwear, a nearly-naked lady positioned halfway between the American flag we had just pledged our allegiance to and the crucifix we had just promised our souls to. I didn’t understand the comments. This whole bra business was just another mystery in my baffled little mind, and the commercial was always the longest thirty seconds of the day. And I was sure that if I watched, the Holy Ghost would know. (This part of the Trinity was represented by a white dove, a seemingly benign entity but one with the power to send me to eternal damnation.) I kept my eyes down and tried to make sense of it all, but as usual, I was confused. “Cross your heart” was something we’d say as an oath, a guarantee that someone was telling the truth.

“Your Dad’s gonna let us light firecrackers in the backyard on the Fourth of July?”

“Yeah. That’s what he said.”

“Cross your heart and hope to die?”

That was the clincher. You had to cross your heart and hope to die. I said it at least once a week, although I had no idea what it meant. What was the point of promising something that would end your life? I didn’t know, but I said it anyway. But this bra thing. What did it have to do with crossing your heart? And it promised to lift and separate something. “You’re suddenly shapelier!” What in the world did that mean? I was sure I would never find out, and had a feeling I wasn’t supposed to. However, the damage was already done. I had thought about watching, and the Holy Ghost was no doubt aware of it. My first Confession was coming up that week, and for me, it was already a matter of everlasting life or death.

Priya

June 16, 2011

Your description of Jesus’ bust is not only interesting, it is thought provoking. I had assumed that church-goers, including children, would automatically see the divinity of the place. I was wrong, it seems. Everything is about learning, no?

PS: You must have been a very sweet kid.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 18, 2011

The problem with most learning, including religious instruction, is that we tend to forget the introduction (or there isn’t one), and so we lose the context of what follows. It’s like when you see a movie for the second time and the first five or ten minutes seem unfamiliar, as though you’d never seen that part before. At least that’s what happens to me. I think it’s because it’s hard to store something in memory when you don’t know what’s going on. I always felt overwhelmed by church and its related events. And because the gaps in my mind were bigger and more numerous than my understanding, I was constantly filling in the holes with my imagination. So the learning part, for me, involved a lot of unlearning, too.

I don’t know how sweet I was. Harmlessly bewildered may be closer. (Some things never change.)

LikeLike

Karyn

June 16, 2011

Another gem because the truth of the matter is as kids we are made to feel guilty about everything. I don’t think that happens with kids today. Maybe parents who grew up in that era didn’t want their kids feeling guilting about watching a commercial that “lifts and separates.” What do I know, I still feel guilty for telling someone off on time in 7th grade .

LikeLike

ALIVE aLwaYs

June 16, 2011

Your fear of the confessional is well taken. I love childhood, we imagine so much, so vivid that when I think about it now, I laugh. You show innocence in childhood, I like that.

I was never that religious and was not persuaded as well, my mother is very religious though, but me, not really. So my childhood fears lie somewhere else, although they are very close to a ghost, but this one is scary and mean, not your good one checking on you. It was the time when we were alone at home, me and my sister, watching a horror movie. She was getting scared, I was too but I did not let it out, instead pretended I am not scared of such television pranks. To show my determination, I decided to take the stairs up the floor, it was very dark and nothing was visible. As I was stepping up, something moved, I trembled and then it looked at me, screaming, rushing down as fast as I could, the shinning eyes, only the eyes were visible, I saw them.

It was a cat, their eyes in dark scare me, damn! But the stairs remained untouched in dark by me!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 18, 2011

You made the mistake most characters make in the horror movies themselves — they always go upstairs in the dark to investigate some mysterious noise. If I’m alone in the dark and I hear a noise, I call a taxi.

LikeLike

Allan Douglas

June 16, 2011

“came back as a test dummy in a stun gun factory” – I almost spit yogurt all over my laptop when I got to that. I’ve definitely got to remember that line – no, I won’t remember it, I’d better write it down.

You do have a way of enlightening us concerning your mistrust of religion. This didn’t take place, by any chance, in a Tibetan monastery?

When I was 5 we lived in the Philippines and my parents took my brother, sister and I to watch the “Easter Parade”. This turned out to be a procession of half-naked young men who beat their own backs as they walked with a cat-of-nine-tails until they were bloody and raw, then were tied to big crosses and left to hang in the sun all afternoon.

I don’t think any of them actually died, and my parents tried to explain the religious and social significance of the display, but I was horrified (and blood spattered) by the overwhelmingly brutal display. I do understand your aversion to the bronze wall hanging.

LikeLike

Margaret Reyes Dempsey

June 16, 2011

Jeez, Allan, that sounds horrible. I’ve heard of these “parades” but your real-life story really brought out the horror for me, especially the blood spattered part. I wonder sometimes if Jesus sadly shakes his head thinking “they just don’t get it.” I’ve never understood the self-mortification thing that many of the Saints engaged in. What purpose does it serve?

LikeLike

Allan Douglas

June 19, 2011

There are passages in the Bible, Margaret, that state that by partaking in the sufferings of Christ we will come to a clearer understanding of Him and make ourselves favored in His sight. Some people (and certain sects) interpret those statements so literally that they do this sort of thing to themselves as an expression of religious fervor. I have come to understand this, but at 5 years old I most certainly did not. I do not, by the way, agree with their interpretation.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 18, 2011

It’s obvious that violence, blood, and death make for irresistible spectacle. That’s been true for thousands of years, and will probably always be true. Sanctioning such activity by relating it to sacred beliefs makes complete sense, if for no other reason than that it appeals to a large number of people.

LikeLike

She's a Maineiac

June 16, 2011

I can’t wait to read part 2. Confession is something so foreign to me, I can only imagine what it was like for a kid. It was enough for me when I’d visit my great-aunt and feel Jesus watching me from her wall pleading and beseeching me to forgive my sins. This line was great: “I might use it if I were about to be thrown from a cliff or set on fire. But in all other situations, I would just ask politely.” I laughed so hard my kids ran over (they loved the cartoons by the way). Oh and one more thing, when are you getting this book published?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 18, 2011

Exactly, Darla: The premise of confession and its effect on young children are two different issues. I’ll try to make that point clearer in Part 2. About the book: I don’t know; I’m still trying to decide if it’s a good idea.

LikeLike

O. Leonard

June 16, 2011

Thanks immensely for the flashback. Isn’t it funny that all who have suffered this parochial school terror have the same stories? Doesn’t matter what part of the country you were from (I grew up in a small town in Wyoming) the horror stories are the same. That last line in the “Hail Mary” has always affected me the way you describe too. I didn’t have the pleasure of Jesus’ picture over my bed, it was worse. It was the crucifix. A twelve-inch model with the horrific murder of Jesus depicted in brass plating and mohogany.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 18, 2011

I wonder if the horror stories are a thing of the past. It seems that at least some of the more terrifying stuff has been toned down or eliminated. I hope so.

LikeLike

Diane Henders

June 16, 2011

My parents were Protestant, so I was spared the horrors. Our church just had a simple cross at the front, and all the pictures of Jesus looked friendly.

But I vividly remember when we went to the funeral of one of my school friends in the Catholic church. Before we went in, my mother carefully explained that “Catholics do things a little differently”. So I was somewhat prepared for the gruesome crucifixes. I feel for your trauma.

LikeLike

Margaret Reyes Dempsey

June 16, 2011

Hi, Diane. I grew up Catholic and I guess I was pretty immune to the crucifixes. However, I did have a shock one day as an adult. I walked into the rectory and hanging on the wall in front of me was a picture called Jesus Laughing. It showed Jesus with his head thrown back in laughter. I was frozen in place for a few moments while I processed that. I think I had a mini-conversion that day and started questioning a lot of the heavy, dark, authoritarian stuff I had been taught. Amazing what a piece of artwork can achieve, no?

LikeLike

Lenore Diane

June 16, 2011

Margaret – that is fascinating! The crucifix didn’t cause you to blink once or twice, but the image of Jesus laughing startled you to a point of questioning things. Wow. That is amazing what a piece of artwork can achieve.

LikeLike

Allan Douglas

June 19, 2011

That’s a great observation, Margaret. Mark Lowery does a song called Jesus Laughing that did the same for me, it’s odd that Jesus is always portrayed as so dark and somber, yet we are admonished to find joy in our relationship with Him. In the song, Mr. Lowery talks about a painting, perhaps it was the same one you saw!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 18, 2011

Diane, I think different children are ready for things at different times. Unfortunately, the way our education system is designed, students are expected to master a specific list of skills and concepts on a pre-arranged schedule. The same is true for religious teachings — or was when I attended Catholic school. I’m sure many kids took it all in stride; I wasn’t one of them.

Attending the funeral of a school friend would be a terrible experience in any setting. I’m sorry you had to go through that.

LikeLike

magsx2

June 16, 2011

Hi,

When I was very young I had to go to Sunday School, but after that my Parents allowed me to make the choice whether or not I wished to go to Church, and as a teenager I was way too busy doing “fun stuff” on Sundays. 🙂

I absolutely loved your last cartoon, that is hilarious.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 19, 2011

I’m assuming your parents weren’t going to church themselves.

Thanks for the comment, Mags.

LikeLike

Jess Witkins

June 16, 2011

Wow, way to bring back scary memories of Catholic school. Starting confession at age 7 sounds spot on to me. I think we did so in first or second grade, and we did have to learn the Apostle’s Creed, but in English. The sad part of that ritual is when it’s used as a threat by teachers. On occasion, the whole class was dragged into the church and made to kneel in the pews in prayer (in silence) until the guilty party of whatever despicable occurrence of the day made themselves known. Not fun.

However, there are beautiful moments in ritual such as the Living Rosary. Did you ever do that growing up? Students volunteered to hold candles for each bead in the rosary, and the church would be dark until we recited the whole thing, light by light. That I remember as a beautiful holy sight, long though it was. It was peaceful.

LikeLike

Margaret Reyes Dempsey

June 16, 2011

It’s so wrong when something that should be spiritual and beautiful is used to make children quake in fear. I think it’s odd that the class was dragged into church until someone made a public confession since confession is supposed to be private. Nothing like using religion as a weapon, huh?

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 19, 2011

I’m glad you said all that, Jess. Sometimes it’s easier to remember the unpleasant things and forget the positive ones. I’m surprised, though, that you had your First Confession at that age. I thought they’d changed it long before you would have been in the second grade.

LikeLike

cre8dsgn

June 16, 2011

Beginning to think I should go to confession…not sure it would help, being Jewish and all.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 19, 2011

Plus, you’d have to book an entire weekend.

LikeLike

Margaret Reyes Dempsey

June 16, 2011

Charles, this post brought back lots of memories even though I was a product of Vatican II. It seems so much effort was spent in the meticulous telling of the sins, with their correct totals, etc., that the whole meaning of the experience was lost. I remember a cousin telling me she was so freaked out that she had no sins to tell one week that she made some up. Epic fail, huh? 🙂

I was a catechist for fifth graders one year. They were good kids. We had a reconciliation service one afternoon and the priest gave his warm and fuzzy forgiveness talk and then proceeded to blast some little kid for not holding the printed program properly in his hands (whatever the heck that meant). I was FURIOUS and when it was all over I had a private meeting with him. I think he was a bit stunned that someone would challenge his behavior, but I definitely noticed a softening in him after that. I find it funny that the worst offenders are always the ones wondering why enrollment is down.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 19, 2011

I guess religious experiences can be like any other kind, Margaret: an individual’s behavior, even a single careless remark, can color our whole outlook. But I know people my age who left the Church and later went back, and others who never left at all. So there must be things that, for them, outweigh any unpleasantness and maintain a powerful pull.

By the way, I made up sins, too.

LikeLike

souldipper

June 16, 2011

As an Anglican, I used to hear my Catholic friends talk about undergoing such torturous matters as “confession”. I was very grateful that we just said a prayer in church on Sunday and, because of the Holy Trinity, all was forgiven – easy/peasy. I used to wonder how on earth Catholic kids ever mustered the courage. You’ve confirmed that it was just as hard as I imagined, Charles!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 19, 2011

I don’t know that it was hard for everyone, Amy. Maybe the ones who were unaffected in those ways tend to be less vocal.

LikeLike

Lenore Diane

June 16, 2011

First, my heart goes out to you with regards to Dr. Stern. That is awful. Horribly awful.

Second, my Mom – to this day – hates ‘shut up’. If we said ‘shut up’ in front of her (not to her, of course), we would get in serious trouble.

Finally, I’ve already used the word fascinating, when I commented on something Margaret said. Still, I have to use the word again …. Not only was your post fascinating but the comments and stories are fascinating, too.

I wish religious leaders would gather adults in a room and let the adults tell them what they thought of various religious symbols, pictures, etc. as a child. The fear that seems to take hold as a child is exactly what should not take hold.

I get so frustrated when religious leaders ruin religion. Regardless of the faith, leave it to the ‘educated’ leader to mess it up.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 19, 2011

Fear is a powerful force, Lenore. Used in the right way, it’s a useful tool that can help guide people along and help them stay out of trouble. Used differently, it can cause permanent damage — and that’s true whether we’re talking about parents, dentists, or religious leaders.

LikeLike

Jessica Sieghart

June 17, 2011

It’s amazing to me how similarly we absorbed these things as children. Other than the music, which I loved, I found a lot of my church experience to be quite scary. I’m sure I told you this, but my father would not let us attend Catholic school because a nun beat the crap out of him once for something his brother did. That alone probably laid the foundation for the scariness, but, I’m sorry, those Confessionals were terribly frightening and downright creepy. I probably went a total of 3 times before I refused to go in one any longer. My parents were surprisingly okay with this and while they went, I just bypassed the middleman and kind of did my own and always gave myself 10 Hail Mary’s. Even as a kid, I realized how much more honest I was with myself during this time. Shortly after, it changed to face to face confessions, which I tried once and then wished I was back in the box. If my soul is stained, then so be it. I don’t feel as though it is.

Another thing that really creeped me out at church was the wine and everyone putting their mouth on the same cup. I’m not even germaphobe, but I refused to do that, too, at First Communion and I’ve never done that.

I’m sure a lot of these things built upon each other resulting in how I feel about church, in general. I tried it for thirty-some years and never felt like I belonged there. I felt it even more so bringing my kids there and to religious education since they were being taught some opinions that I strongly disagreed with. They’d come home and I’d completely undo what they had been taught. The sex scandals really started becoming breaking news and we were sitting in church one Sunday and it dawned on me that two of the people serving Communion were my neighbors. One consumes far too much alcohol and beats his wife all the time. The police are always over there. The second was a mom from the neighborhood who I had just heard use “a slang word for Mexicans” out in the parking lot on the way in. She also worked at the high school and completely walked out on her husband and two small girls after she “fell in love” with a gym teacher there. I know I shouldn’t be judgmental and those things are none of my business, but I just stopped and thought “What the heck am I doing here?,” grabbed the kids, walked out and never went back. I don’t miss it.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 21, 2011

I remember the change over to face-to-face Confession; are they still doing that? And I never thought of the fact that hundreds of people were sipping wine from the same cup. If there’s ever a lull in your life, Jessica, I hope you’ll write about some of these things on your blog. Or save them for the television show.

LikeLike

Snoring Dog Studio

June 17, 2011

Charles, you have a gift for bringing forth memories that pull your readers in. This post was hilarious, touching on so many memorable experiences I had as a young Catholic. I remember the moments AFTER confession, picturing my soul pure white, clean, so clean! smelling like freshly laundered towels. I agonized over how on earth I could keep my soul pure for the rest of the days until I had to go to confession again. And each time I transgressed, I could envision tiny spots of dirt and blackness sticking to my soul. It would have been far easier to have stayed in the confessional – taken up residence there. But then, I had to go home and FACE MY ANNOYING BROTHERS. I didn’t have the patience of a saint. I was just a kid trying to hold my own in a chaotic household. I’m surprised they could say enough Hail Mary’s to be forgiven!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 21, 2011

There was one nun who told us that even after Confession, the sins didn’t completely disappear, and that there was always a shadow left behind. I related it to erasing something written in pencil — if you looked at just the right angle, you could still make out what used to be there. This completely ruined that feeling of a sparkling clean soul. And speaking of annoying brothers (and sisters), I wonder if only-children tended to have shorter confessions.

LikeLike

Melinda

June 17, 2011

I’m not Catholic, so I never experienced confession, but I’m sure I would have been terrified and made up more things to confess to. I’m a true believer in karma, and hope the dentist is enjoying his time. 🙂 That was great!!

I remember how horrified I was at those Cross Your Heart commercials even as a little girl. Now that I look back at all the censorship of that time and what was considered “appropriate for TV” then, I’m really shocked they were able to get away with that. This would also be the same time that I was fascinated by the Playtex commercials and wondered what was in those boxes that allowed people to swim better, do cartwheels, and jump extra high on a trampoline.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 21, 2011

We must remember those commercials because, as you said, there was so much censorship back then. The bra ads were about the most embarrassing thing that would ever appear on a television screen. These days, there isn’t anything that goes unmentioned in commercials. And of course there’s a remedy for everything, including conditions we didn’t know we had.

LikeLike

heidit

June 17, 2011

Wonderful post, Charles. Not being Catholic, I don’t know how I would have reacted to what you went through, but I’m glad you’ve shared your stories.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 21, 2011

Thank you, Heidi. I’m pretty sure you would have reacted the same way — by writing about it.

LikeLike

Mitch Mitchell

June 19, 2011

Cross Your Heart bras; man, I’d totally forgotten about those commercials!

As to the other, not being Catholic I never had to deal with confessionals. But to tell you the truth, I never got this “sin” thing as a kid. I would hear about it but no one could ever really say what it was supposed to be. We used to get “it’s when you’re bad” and I got that but then I heard that thinking bad stuff was also a sin and I thought that was stupid. Then I’d hear people calling almost everything a sin and decided it just wasn’t for me.

As for the dentist… moving around like I did I never got on a first or second name basis with any of them, but I hated them all! lol

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 21, 2011

It was unsettling to be told that thoughts could be sins, too, because you know what it’s like when you try not to think about something. How much control do we have over our thoughts?

Thanks for the comment, Mitch.

LikeLike

shoreacres

June 19, 2011

You know how you can walk through a patch of woods and see just a flicker and flash of a bird, but never get to really see it? And then one day, there it is, just sitting on a branch looking at you and you gasp because it’s so beautiful?

Well. Sometimes insights are like that, and I just got one. Every time I hear my Catholic friends talk about confession, it comes paired with penance. After I became a Lutheran, I never heard about penance. Confession was paired with absolution. I was taught you never, ever tear them apart, any more than you’d tear apart law-and-gospel or saint-and-sinner. Each phrase represents a dynamic reality, two poles we’re continually moving between.

From where I sit today, confession’s not about nit-picking infractions, imagined or real. It’s about learning to take responsibility. As a dear professor once said, it’s all about learning to say, “I…..”

I wonder if that prof is still teaching, and if he’d take Tony Weiner into his class?

LikeLike

Marie

June 21, 2011

Shoreacres, thanks for leading me to the insight that confession-penance/responsibility-absolution is somewhat like another holy trinity!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 21, 2011

One of the problems I had with Confession was exactly that, Linda: the focus on penance rather than learning and growth. The confessional, then, became something like a car wash you visited once a week to wash off the dirt of life. Or maybe that repeat business was really the whole point.

Thank you for a great comment.

LikeLike

Kevin Glew

June 20, 2011

Another excellent piece, Charles. I don’t know much about Catholicism, but some of its practices certainly seem antiquated and destined to make people feel guilty for their entire lives. I consider myself an agnostic, but I probably “sin” far more than I should (according to the Catholic definition of sin). Thanks for writing this.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 21, 2011

The world could probably use a little more guilt, Kevin, but applied in the right proportions and for the right reasons. As young Catholic schoolchildren, we were marinated in guilt. The message seemed to be that being human was a sin, and an unavoidable one.

LikeLike

Betty Londergan

June 20, 2011

Wow … so many great comments, Charles! I was raised Catholic, too, so this totally resonated with me. I used to lie awake in the dark and instead of saying the rosary (my mom’s big love) I would lie there hoping beyond hope that the prayer we just recited …”if I should die before I wake…” (a weird children’s prayer if ever there was one) ..wouldn’t come true because my soul was totally splattered with mortal sins from “thinking unpure thoughts” that Sister Agnes Adele had assured us would send us straight to hell. You didn’t have to actually DO anything naughty — but just thinking about bras, or lifting and separating body parts, or any exciting body parts period — was going to send you to a life of eternal damnation. And what kid isn’t thinking unpure thoughts pretty much continuously?? And how could you stop your mind from thinking, even if you wanted to?

It was a torturous mystery (and that wasn’t one of the rosary mysteries).

Also loved your description of your dentist — our Dentist Sklut wanted to drill for hidden cavities — thank God my mom was too thrifty to spring for that!!

love the way you bring it all back, B

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 21, 2011

Betty, I’d love to hear about your current church. I know you’ve referred to it many times on your blog, always in glowing terms.

Was your dentist really named Doctor Sklut?

LikeLike

Linda Paul

June 20, 2011

As usual, Charles, I learned all sorts of stuff from this post. I love your posts because they almost always shed light upon some mystery for me.

Having been raised in a totally a-religious environment (bless you, my mother!), the entire notion of confession spooked the hell out of me, especially after, as a young adult, I actually stepped inside one of those ancient gothic cathedrals in Germany and gazed in wonder at the confessional booths that looked like something out of a macabre circus act.

I came away from those cathedrals…and their dark filligreed confessional booths, with an understanding of how religion, through the ages, has controlled people. In return for explanations of the unknown, people forfeited their intellect, their ability to think independently and to ask questions. One’s eternal survival became more important than one’s present circumstances. That eternal survival question forced believers into an impossible life of fear and inhumanity. Obviously, the cards are stacked against mere mortals.

I reserve great honor and respect for those individuals who were raised in this confined lunacy, but have been able to rise above the fear and anxiety to look upon life with reason and sanity.

Jesus = “A head mounted on the wall.” Now THIS was priceless! I never understood these icons till I read this passage in your blog. There’s not much to separate Jesus’ disembodied head from the disembodied heads of lions, tigers, deer, elk, moose, elephants, and any other trophy hunters’ prizes! Jesus as a trophy. Yikes.

I love this post. Please forgive me if my response is too cynically sacriligious.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 21, 2011

Linda, it’s great to hear from you. I’m continually amazed by the wide range of experiences people have had growing up with various religious teachings — or none at all. So much of the dogma does seem to be about control. But some people manage to get out from under that, either escaping completely or finding ways to make religion and their lives more compatible.

LikeLike

writerwoman61

June 24, 2011

I’d like to confess that I don’t “do” organized religion any more…I gave it up nearly 40 years ago! Surprisingly, I’m still alive. Confession must be a terrifying thing…

I remember those bra commercials too…not a fan…Playtex bras were always so pointy in those days!

Can’t wait for Part 2, Charles!

Wendy

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 25, 2011

Organized religion works for a lot of people. It would work even better if everyone were free to make their own choices, rather than first having to reverse the effects of early childhood brainwashing. Thank you for the comment, Wendy. I always welcome your opinion.

LikeLike

Brown Sugar Britches

June 27, 2011

wow! that was hilarious! i went to catholic school for a short time: third, fourth and fifth grades. i was not “technically” supposed to be there, but my mother and grandmother did not share the same views regarding me and my future, so my grandmother felt it wise to relocate me from public school to catholic school. i confessed, i took communion, i prayed and then i was told not to. why? because i was “technically” not catholic as i had not been baptized. well, that was news to me. i went to a catholic school, with catholic teachers and catholic students. in my mind i was catholic, although, i truly had no understanding of what it was, why it was different and why i wasn’t one. i wore a uniform and knee socks perpetually stained from the smashed olives littering the playground. i thought i was catholic and was somehow completely disappointed to find out otherwise. i had to stay seated when it was time to take communion and allow the other children to pass. for whatever reason, they did not revoke my praying and confessing privileges. i was a delicate child during those years and thankfully i did not confess in the same location that you described. we went into a personal chambers of sorts. lush carpeting, beautiful stained glass windows, and an ornate chair of dark wood with a cushy red velvet covered seat. i didn’t mind the time away from the other children, the nuns, the school. i particularly liked “confessing”, for two reason: ten minutes of presumed solitude and the opportunity to stare endlessly at the glowing sunlight stained glass windows.

i really enjoy your blog.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

June 27, 2011

I don’t know, BSB — that sounds like a full-blown post to me. Have you written about it? Why didn’t they just schedule a belated baptism for you, rather than alienating you like that? Whatever the reason, I think it would make a great story: instead of being forced into Communion, you were denied the right. I’d love to read more.

LikeLike

dearrosie

June 28, 2011

Oh man Bronx Boy you are a great story teller. As I’m not Catholic I really enjoyed your explanations. Sheesh I don’t know anyone else could write about a 7 year old boy’s Catholic School memories of confessions and cross your heart bras and a sadist dentist. Bravo!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 1, 2011

Thanks, Rose. It is quite a jumble, isn’t it? I think everyone’s childhood probably feels like that.

LikeLike

arborfamiliae

June 28, 2011

As a Protestant I always had the perception that when Catholics went to confession they were given some easy task to complete (“Say three Hail Marys”) and then they could consider themselves absolved of their sin.

I thought Catholics got off easy. I didn’t have anybody to tell me that if I repeated a few easy words (I would have even been willing to do them in Latin), I could be assured I was ok. I had to trust that God really heard me and forgave me.

I still get a little shiver when I hear somebody say “ego te absolvo.”

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 1, 2011

For believing Catholics, though, that moment was as good as it got. And hearing it in Latin somehow made it more official, and more satisfying. The week was all downhill from there.

LikeLike

Damyanti

June 29, 2011

I haven’t been here for a while, and now I’m going to go back and read everything I missed.

I love how you make us laugh, but I adore how you take us back into your mind as a child…it appeals to me as a writer, and I wish I could write children POVs as well as you do. 🙂

LikeLike

bronxboy55

July 1, 2011

You’ve been busy, I know, and I feel as though I haven’t visited your blog in a long time. I’m sure there’s brilliance waiting for me there.

LikeLike

Jennie_Lately

October 15, 2011

Hello. I just discovered your blog today.. I am hooked.

LikeLike

bronxboy55

October 18, 2011

Thank you. I hope you’re equally hooked on developing your own blog. I look forward to reading it.

LikeLike

worrywarts-guide-to-weight-sex-and-marriage

November 17, 2011

I’m new to blogging. Initially I started as a way to share a family trip (celebrating college and high school graduations) to Thailand, with our friends while we traveled, but realized mid-trip that writing about it was keeping me sane, the way writing kept me sane when the kids were little.

When we returned home, I realized I wanted to keep writing. Eventually, I realized (probably around the time I stumbled upon your blog), that I love reading blogs just as much as writing them. Then I discovered the connecting part of it.

I’m sure I’m way behind in this evolutionary process, but enjoying every moment of my blogging metamorphosis. My most recent revelation was a “bright” idea mostly inspired by reading your blog. Having a page dedicated to blogs I love. I realize this is not an original idea (given Freshly Pressed and the blogroll thing), however, I wanted to share specifically with my friends and offer up more than a link.

I was inspired by your line (a line I heard almost daily during the past ten years), “Why are you even saying this?” and have titled the page “Y R U Even Saying This.” I hope you don’t mind, but your blog is the first one I am featuring. If you do mind, let me know and I will choose another.

Thanks for all of the inspiration!

LikeLike

bronxboy55

November 17, 2011

You say you’re new to blogging, but I wouldn’t have guessed that. Your writing is wonderful, and this new series of pages you’ve created obviously took some formatting skills that I don’t have — the clickable book, for example. Thank you for including me.

LikeLike